Writer’s block. Oh, that detestable villain!

For any struggling authors out there, rest assured that your beloved science fiction and fantasy authors have encountered the same problems and overcome them. Here is a collection of essential writing advice from sci-fi and fantasy writers to help you craft a beautiful story—and remember, like every writing rule, you are allowed to break these as you see fit.

1. Keep everything you write.

Let’s say you finished your first draft. Most first drafts are kind of like ugly potatoes. You know it’ll make some tasty French fries in the end, but you need to cut off some lumpy spots before you can do any real cooking.

Well, when you cut off those ugly parts, make sure you save them somewhere for later. So advised C.S. Lewis in a letter to a young girl asking for writing tips:

“When you give up a bit of work don’t (unless it is hopelessly bad) throw it away. Put it in a drawer. It may come in useful later. Much of my best work, or what I think my best, is the re-writing of things begun and abandoned years earlier.”

Lewis wrote 30 books in his lifetime, including The Chronicles of Narnia. That’s plenty of words published, with even more drafts rolling around his desk drawers to inspire him later.

So cut those ugly bits out and save them in another draft! Maybe call it your “ugly potato babies,” or “the boneyard” if you want to be gothic. Like potato eyes sprout into new potatoes, you might just find yourself with another manuscript down the line.

2. Do the reader's job for them.

It’s a joy of writing, when you create that one beautiful, perfect sentence. But what makes it perfect?

Most likely, it's beautiful because of sensory details. Sci-fi writer and Damon Knight Grand Master Nalo Hopkinson explains this in her TED-Ed lesson, “How to Write Descriptively.” These senses include taste, smell, touch, hearing, sight—and, critically, motion. Delightful writing will combine senses in a new way that evokes complex associations for readers.

And immersive writing will avoid cliches.

“Writers are always told to avoid cliches because there’s very little engagement for the reader in an overused image such as red as a rose,” Hopkinson's lesson explains. “But give them ‘love… began on a beach. It began that day when Jacob saw Annette in that stewed-cherry dress.’ And their brains engage in the absorbing task of figuring out what a stewed-cherry dress is like. Suddenly, they’re on the beach about to fall in love. They’re experiencing the story at both a visceral and a conceptual level, meeting the writer halfway in the imaginative play of creating a dynamic world of the senses.”

Sensory details allow a reader to immerse themselves into your work rather than being told what to think. They’re more fun to write, and they’re more fun to read.

RELATED: The Best Books on Writing by Sci-Fi and Fantasy Authors

3. Always carry writing materials with you.

Every writer has some version of this story: You’re happily asleep, drifting through dreams, when suddenly everything sharpens into focus. You've just envisioned a story with cinema-level stakes. Your body bursts awake and you think, 'Wow. That’s a great idea for a novel! I’ll write it in the morning.'

Writer, do you ever remember it in the morning? I don’t. I always forget.

Maybe it occurs in a different way. Maybe you’re riding the bus home from work and you see somebody doing something interesting through a shop window. Maybe you’re watching a movie, and the characters do something that reminds you of a sticky situation your protagonist gets into. Maybe your cat just does something really funny and you want to save it for later. Capture each of these moments—every snippet of a scene or a plot idea or a sentence fragment.

Jeff VanderMeer, author of Annihilation and Borne, does this. In a piece sharing his writing secrets, VanderMeer says he carries a pen and notecards with him at all times. And he keeps them on his nightstand. And there’s scattered paper in his kitchen, too.

“Over the past twenty years especially, I have not lost or forgotten a single idea or scene fragment or character observation or bit of dialogue because I have always written it down immediately, no matter what situation I’m in (this includes when I had a day job),” Vandermeer writes.

Not only does the practice preserve his muse, it also encourages his subconscious to continue generating ideas.

“If your subconscious brain ‘knows’ you are going to write it all down and use what it gives you, a loop is created where, at times, and depending on other factors, the problem isn’t lack of ideas but having too many ideas,” VanderMeer writes.

Writing everything down keeps you in the good habit of opening your mind to ideas, wherever they come from.

4. Create diligent writing habits.

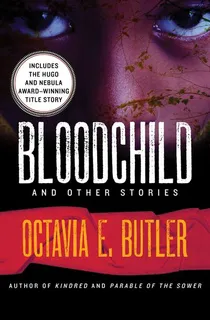

Every writer has some variation of this advice, but the MacArthur Genius Grant Award-winner Octavia Butler was perhaps the most assertive about it. From her essay, “Furor Scribendi":

“Forget inspiration,” she writes. “Habit is more dependable. Habit will sustain you whether you’re inspired or not. Habit will help you finish and polish your stories. Inspiration won’t. Habit is persistence and practice.”

The two habits Butler advises are 1. Read every day and 2. Write every day. Every day, she says. You have to carve out time for these activities.

“Choose a time of day,” Butler says. “Perhaps you can get up an hour earlier, stay up an hour later, give up an hour of recreation, or even give up your lunch hour.”

And if you don’t have time to read, Butler says listening to books on tape is just as good. (Say that the next time Twitter discourse starts about audiobooks versus physical books.)

Butler emphasizes habit because it’s the key to getting past the hardships of writing life.

“Persistence is essential to any writer—the persistence to finish your work, to keep writing in spite of rejection, to keep reading, studying, submitting work for sale.”

"Forget talent," she says. Talent will grow the more you practice.

You can read Butler's complete essay in her anthology collection, below.

5. Feed your ideas with research.

Engaging SFF stories invite us to immersive worlds. Many of these are completely new to us, with unfamiliar ecosystems, biologies, and cultures. Yet, they become familiar through skillful worldbuilding. A good writer can make us feel like we’ve lived in their world as long as their characters have. Worldbuilding skills come from confidence and attention to detail. They keep SFF vibrant.

But worldbuilding takes a lot of time and attention, not to mention confidence that your ideas are interesting. And that’s scary for lots of writers.

“Fear of worldbuilding is why we see so many similar worlds done to death," N.K. Jemisin, worldbuilder extraordinaire, writes in Growing Your Iceberg. “Iron Age barbarians, Star Trek-ian space navies, medieval northern Europe ad infinitum. Easier to copy than create.”

Don’t fear the worldbuilding process, Jemisin says. Embrace your wildest ideas. Give them all the attention they need.

Jemisin won three consecutive Hugo Best Novel Awards, in part because her worldbuilding is astoundingly rich and innovative. She makes purposeful choices about characters’ details, and she elucidates the consequences of those choices throughout their environment.

It takes lots of research—within limits. Research is your friend, Jemisin writes, but also, you can’t research forever, nor should you. Speculative worlds must engage, not just educate or entertain.

“Use enough science to make sense to the layperson, and no more,” she writes. Your writing will sell the more unbelievable elements. And, “Don’t forget the social sciences!”

For more invaluable advice from Jemisin, check out her MasterClass.

6. Read, read, read.

All the experts agree; to get better at writing SFF, you need to read it constantly.

So advised the legend himself, Sir Terry Pratchett, in an interview with Writers Online. He said, “To write good SF and to write good fantasy, like anything else, you have to have actually studied it…But you have to read everybody, not just the SF guys. It’s just following the masters. See how the best are doing it.”

Neil Gaiman calls it the compost heap in his MasterClass. “Everything you read, things that you write, things that you listen to, people you encounter—they can all go on the compost heap, and they will rot down, and out of them grow beautiful stories.”

Read all genres—anything and everything you love. You never know what seeds will sprout after it all intermingles. And then, when you find a book that snatches your heart and won’t let go, figure out why. Which brings us to our last piece of advice...

7. Pay attention to the sentence level.

In an interview published in The Paris Review, Ray Bradbury recalled how he loved Eudora Welty’s writing. He studied how she packed so much detail in a single line.

“In one sweep she gave you the feel of the room, the sense of the woman’s character, and the action itself. All in twenty words. And you say, How’d she do that? What adjective? What verb? What noun? How did she select them and put them together?”

Asking those questions is precisely how you figure it out. Grammar and vocabulary are a writer’s most necessary tools. Pay close attention to how your favorite writers wield them. It’ll help you get a handle on your own voice, the one thing nobody else can copy.