It’s easy to think of post-apocalyptic fiction as a single category, but not every apocalypse is built the same.

The world’s most famous post-apocalyptic stories tend to have only one consistent element between them: a lot of people have died. In The Stand, it’s a pandemic.

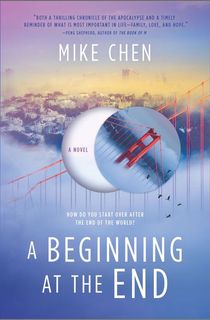

In The Walking Dead, it’s zombies. In my upcoming novel, A Beginning at the End, it’s also a pandemic, but one that has been contained enough that 20% of the population remains to keep a skeletal society functioning.

In the popular Fallout series of video games, it’s nuclear holocaust.

RELATED: 8 Vital Sci-Fi Climate Change Books

Recent years have seen the rise of the real-world climate crisis influencing fiction, enabling media to examine how such encroaching disasters would change the world.

This would likely not only remove vast swatches of population but also redistribute resources and communities in different ways, such as the floating city of Qaanaaq in Sam J. Miller’s Hugo–and Nebula–nominated Blackfish City.

Still from The Walking Dead.

Photo Credit: AMCOf course, the apocalypse is often a metaphor for fears of something else: commercialism, racial conflict, political extremism, climate change, and more. How those stories are put together is something different altogether.

So many variables factor into creating a post-apocalyptic world, from the actual catastrophic event to the amount of people remaining, and what motivates them.

RELATED: 50 of the Best Science Fiction Books Ever

If you’re going to take a try at the apocalypse, here are 10 worldbuilding questions to ask yourself as a guideline for rebooting the world.

1. What caused the apocalypse?

If the world’s ending, you need to know how, because the reader will want that information. At the same time, that decision defines many aspects of your story.

A zombie apocalypse is much different from a climate-change apocalypse, which is also much different from a pandemic.

This decision creates guidelines for how the world will evolve after the apocalyptic event, so make it one of your first choices when creating your post-apocalyptic world.

2. Is it still a threat?

Whatever triggers the apocalypse will generate some level of challenge for the survivors, but there’s a big difference between a lingering risk and an active threat.

For example, if something takes place after a single isolated event wipes out a large portion of population — like if malware caused every smartphone to suddenly explode—then there’d be no concern; the risks in that world would be due to lawlessness and lack of infrastructure/resources, but not an active threat.

RELATED: 16 Powerful Post-Apocalyptic Books

However, in a zombie story, the cause of the apocalypse is still a direct threat to survival.

A climate crisis and a pandemic might see something in between based on their specific circumstances, but the severity of the threat will dictate how characters treat day-to-day living.

3. How many years have passed?

The number of years following the world-killing event is key to your characters’ behavior. If it’s just weeks or months, desperation and urgency will often go hand in hand with confusion and fear.

However, if a generation has passed—especially if a story takes place through the eyes of a younger person—characters will have adapted to the new world, giving day-to-day experience the chance for exploring unique details of life after the apocalypse.

From the cover of The Stand by Stephen King.

4. How many people survived?

In fiction, an apocalyptic event can come at many different scales. Some stories still leave mere thousands in the world, meaning that human interaction becomes a rarity in daily life.

Others tell stories where millions, perhaps even a billion people survive—and how they form communities dictates the possibilities and constraints of that world.

The presence (or lack thereof) of other people can affect the physical and emotional progress of a story, making it a key factor that will ripple into countless other decisions for your narrative.

RELATED: 10 Solarpunk Books for When You Crave Optimistic Sci-Fi

The choices I made for A Beginning At The End focused on keeping a high enough population (2 billion) to have city-states and various communities, allowing for an exploration of how people might live in such a balance.

On the other hand, something like Stephen King’s The Stand wipes out 99.4% of the population, allowing for many different narrative possibilities between survivors.

5. What infrastructure remains?

Infrastructure seems like an extremely boring topic to many, and in our modern world, it’s the mundane realm of roads, power grids, plumbing, and other such needs. But when you take any of those daily necessities away, suddenly life becomes much more complicated.

There’s very little chance that a post-apocalyptic world manages to keep a complete infrastructure system, so picking and choosing what remains and what is damaged beyond repair allows creators to adjust the levers on various types of human needs—and the desperation that kicks in when those needs aren't met.

6. How do people eat?

Without food, the human race goes extinct. Which means that the ability to grow and harvest food will drive both the logistics of community and the economics of the new world.

Other factors include how the land will support vegetable growth due to apocalyptic factors, such as irradiated farmland, and if communities can be secured enough to raise livestock.

Food preservation and cooking technologies will also indicate the general quality of life for the population. If people have thriving communities with kitchens of some form, it’s a far different experience from day-to-day hunting.

7. Where do people live?

The apocalypse will cause a redistribution of resources, with an additional impact on access to those resources.

For example, a climate apocalypse will have clear implications on geography, but unexpected changes such as rising sea levels might cut off access to other resources.

Similarly, in a zombie apocalypse farmland may have to be secured from that constant threat. It also may be easier for characters to inhabit physically protected areas surrounded by water or at higher elevation.

These issues will dictate where people congregate as communities, as well as how they interact with other people.

In A Beginning At The End, I divided survivors into three communities: metropolitan cities which replicated pre-apocalyptic life with a nominal level of infrastructure; communes that reclaimed college campuses; and gangs that roamed wastelands. Each represented different levels of resources and economic means, and each has something the others need.

RELATED: 10 Shocking Dystopian Fiction Books

8. How do people travel, if they travel?

In many apocalyptic films and TV shows, cars are constantly in use. Which doesn’t make a lot of sense given the limits of gasoline, even with a reduced population.

However, if your world addresses that, and the logistics of keeping cars—and maybe even airplanes—running, then that creates a far different experience than something where horses and bicycles are the biggest means of off-foot transportation.

Travel, of course, opens the door to many different practicalities of worldbuilding, from trade to communication to resource scavenging.

Thus, a clear ruleset for safe travels in a post-apocalyptic world allows your story and characters to have an appropriate sense of scope.

9. What does religion look like?

Organized religion has been around since the earliest human societies, and there’s every reason to assume that some form of faith would continue after the apocalypse.

This provides many narrative opportunities, as a catastrophic event can easily be twisted into a cult-like understanding; similarly, existing religious beliefs can evolve into something that conforms to the new world.

RELATED: The 10 Best Science Fiction and Fantasy Books of 2019

When worldbuilding religion, one of the biggest variables is the scope of time for a story.

Early post-apocalyptic days will probably have more of a “why hast thou forsaken me?” religious vibe compared to several generations later, which will have adapted religion into the logistics of everyday life.

10. How has art survived?

Art can inspire. It can pass knowledge on to the next generation, it can keep the past alive. Art can reflect a culture or it can create a change in culture. All of these things flow through creativity, which is essential to humanity in whatever form it takes, from cave paintings to Shakespearean plays to modern-day comic books.

Even in an apocalypse, art can—and should—live on. How it lives on is where it gets interesting. Does technology still work? Are there traveling performers, like in Emily St. John Mandel’s seminal Station Eleven? Or does it represent a mere historic chronicle of a different life?

RELATED: 10 of the Best Books on Writing by Sci-Fi and Fantasy Authors

Art is intrinsically tied to the human experience, and exploring this in catastrophic situations provides a deeper window into your world and characters.

Featured photo: Kovah / Unsplash