Odds are, you’ve seen a Green Man or two in your day. Maybe it was carved on a cornerstone of a church or other building, maybe it was a piece of public art or the cover of a fantasy novel, or maybe it was just a kitschy piece of décor you could buy at just about any garden center in the country.

In fact, Green Men are everywhere, or so it would seem. But for such a ubiquitous figure, the Green Man of folklore remains surprisingly mysterious.

The earliest known instances of Green Man sculptures date back to at least the 2nd century, as catalogued by British singer/songwriter Mike Harding in his book A Little Book of the Green Man. Harding notes examples of the figure from Lebanon and Iraq, while other anthropologists have pointed out similar figures from ancient India, Nepal, and Borneo.

Lintel from central Java, 9th century.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia CommonsThese early sculptures – and, indeed, most visual depictions of the Green Man throughout history – show a humanoid face, often shaped from leaves and other vegetation.

Julia Hamilton, who married Fitzroy Richard Somerset, Baron Raglan to become Lady Raglan, is thought to have coined the term “Green Man” in a 1939 article in The Folklore Journal. In “The Green Man in Church Architecture,” she explored the contradictory relationship between this seemingly pagan figure and Christian art.

And, indeed, the figure is almost always male. While Green Women do exist, they are exceedingly rare.

Green Men, on the other hand, are ubiquitous as architectural decorations. So much so, that the figure has been classified into three distinct types.

Perhaps the most common, and the one most often associated with the figure of the Green Man in modern culture, is what’s known as the Foliate Head – a humanoid face completely covered in, or formed from, green leaves.

Less common but no less ancient is the Disgorging Head, which may or may not look vegetative on its own but is spewing forth greenery from its mouth. One of the oldest surviving examples of a Disgorging Green Man is from St. Abre in St. Hillaire-le-grand, France, which dates back to around 400 CE, according to William Anderson’s 1990 book on the subject, Green Man.

Disgorging Green Man in Ludlow Church.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia CommonsThe third type of classical Green Man figure is the sinisterly-named Bloodsucker Head. In this case, rather than spewing vegetation from its mouth, the face sprouts greenery from every orifice – eyes, ears, nose, and mouth.

These are similar to common gravestone carvings, which often depict plants growing from skulls, to symbolize death and rebirth.

Countless variations on all three of these types occur with regularity, on buildings both sacred and secular, all over the world, though the Green Man figure is particularly popular in England, where numerous pubs bear his name. (One such is famously featured in Robin Hardy’s 1973 folk horror classic The Wicker Man, and referenced in the Rob Zombie song “The Ballad of Resurrection Joe.”)

Scene inside "The Green Man" pub in the 1973 Wicker Man.

Photo Credit: British Lion FilmsBut who is the Green Man, and how did he come to be featured in so many sculptures throughout history? No one really knows.

In modern paganism, the Green Man is often used to represent ecological awareness or seasonal renewal – growth and life. He has been associated with everything from the Greek god Pan, to the Celtic Cernunnos, to vegetative deities like Dionysus or the Welsh Blodeuwedd, to the medieval woodwose or “wildman of the wood.”

The true origins and nature of the Green Man are unknown, however, and there are some who believe that the idea of the figure evolved independently in countless folkloric traditions, explaining its widespread appearance. Others have suggested that the ubiquity of the Green Man figure was exported around the globe along with colonialism.

“Sometimes a Green Man carving is given a particular title,” writes Phill Lister in his paper, “Who is the Green Man?” compiled for the 1983 Fools & Animals Unconvention in Wath-upon-Dearne, England.

"This has led many to seek clues in myth, legend and religion. John Barleycorn – celebrated in song – shows the same themes of death and rebirth, as does the Green Knight in the Arthurian story of Sir Gawain. Medieval legends of the Wild Men – dressed in leaves, living in the forest and venturing forth to take food, have been connected with the Green Man. In some stories of Robin Hood – the robber and hero dressed in green – he attains godlike status and links with the Horned God Herne.”

RELATED: 10 Magical Fantasy Books Inspired by Irish Mythology

The Green Man by sculptor Toin Adams at the Custard Factory, Birmingham, England.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia CommonsIn the folkloric traditions of the United Kingdom – where the motif of the Green Man is inescapable – other, similar figures frequently crop up.

During May Day celebrations, one person often dresses as Jack o’ the Green, in a conical wicker or wood framework decorated with foliage, while the oldest apple tree in an orchard is known as the Apple Tree Man.

Nor are such figures restricted to the lore of the British Isles. In America, Johnny Appleseed may have been a real person named John Chapman, who helped introduce apple trees to large parts of Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, and Pennsylvania. But the legend that grew up around him – even while he was still alive – shares many similarities to these kinds of folkloric characters.

RELATED: The Chilling True Story Behind the Pied Piper of Hamelin

Johnny Appleseed statue in Lancaster, Ma.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia CommonsWhile Green Man figures date back to as early as the 2nd century, they experienced a surge in popularity in the 19th century in England; a surge that, to some extent, they still enjoy today, all over the world.

As such, the lore of the Green Man isn’t limited to antiquity. Countless books, poems, songs, and plays – not to mention art, from illustration to sculpture to stained glass to mask-making – have incorporated the iconography of the Green Man over the course of the last two hundred years.

As we saw above, the Green Man has been linked to classic storybook figures like Robin Hood and Peter Pan, whose name is often thought to be a reference to the Greek god. In Arthurian legend, the figure of the Green Knight – who serves as both antagonist and mentor to Sir Gawain – is often seen as a parallel of the Green Man, and is usually depicted as wreathed in vines and leaves.

Sean Connery even played the Green Knight in such a vegetative getup in the 1980 film Sword of the Valiant, opposite Miles O’Keeffe as Gawain. The narrative of the Green Knight and Sir Gawain has frequently been interpreted as concerning the conflict between paganism and Christianity, as the latter gradually accepts the teachings of the former. Such is also a regular reading of the presence of Green Man sculptures on church buildings.

More recently, the works of countless fantasists have incorporated elements of the Green Man motif and mythology. In J. R. R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings series, both the ambulatory trees known as Ents and the figure of Tom Bombadil share elements of the figure, while Robert Jordan’s epic Wheel of Time series features a character referred to as the Green Man, who is the last of a race who were once the gardeners of the world.

Even Kenneth Grahame’s 1908 children’s classic The Wind in the Willows features a Green Man-like figure.

An ent from Tolkien's Middle-earth.

Photo Credit: New Line CinemaAs a motif most closely associated with the natural world, the Green Man has increasingly been featured as a benevolent force in fictional interpretations, but such is not always the case.

Kingsley Amis’ 1969 novel The Green Man not only features an inn of that name but also, eventually, a manifestation of the Green Man himself in the form of a murderous pagan monster of sticks and branches. Australian author Terry Dowling’s haunting short story, “The Bullet That Grows in the Gun,” also features a sinister, ghostly figure known as the Green Man.

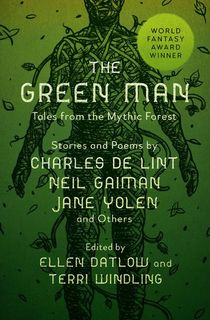

In 2002, Ellen Datlow and Terri Windling edited an anthology of tales “centering around the legendary myth of the Green Man – the spirit who embodies Nature in its most untamed form.” Contributors include Neil Gaiman, Jeffrey Ford, Kathe Koja, Jane Yolen, Gregory Maguire, Tanith Lee, Charles de Lint, and others.

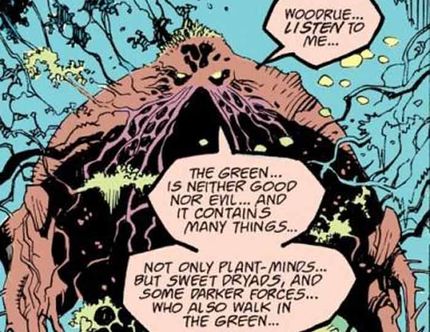

This wasn’t the only time Gaiman dabbled in the legend of the Green Man, either. Comic book figures like DC’s Swamp Thing and Marvel’s Man-Thing – themselves part of a long tradition going back to a shaggy creature called The Heap that first appeared in Air Fighters Comics in 1943 and, before that, to Theodore Sturgeon’s legendary short story “It" – have long been associated with the verdant Green Man. It was Alan Moore’s run in Swamp Thing which made some of those connections more overt.

Later, in a short in one issue of Swamp Thing Annual called “Shaggy God Stories,” Gaiman picked up those connections and continued to run with them, tying Swamp Thing to Osiris, the Garden of Eden, and much more, all in a few short pages.

“I’ve seen them,” Gaiman writes in the short story, the words laid over a series of faces similar to Swamp Thing’s, all drawn by Mike Mignola. “Faces in the Green.”

So, it turns out, have all of us.