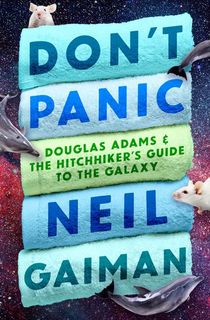

In October 2018, Neil Gaiman's book Don't Panic: Douglas Adams & The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy was released as an eBook for the first time ever. A celebration of the life and work of Hitchhiker's Guide creator Douglas Adams, Gaiman's book about his friend and contemporary was first released in 1988.

Since then, Don't Panic has been revised to reflect Adams' later work, as well as his sudden passing in 2001 at 49. The unique book combines biography, scripts, and reflections from Adams' friends, family, and coworkers to create a fascinating picture of a man who Gaiman writes could be “serious and funny and faintly baffled, all at the same time."

RELATED: 10 Hilarious Douglas Adams Quotes

Douglas Adams.

Photo Credit: AlchetronFans of The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy series, Dirk Gently, Doctor Who, or any of the other works to which Adams brought his irreplaceable style and wit will find much to enjoy in Don't Panic. But readers who aren't already familiar with Adams' work will also appreciate this look at a masterful, if occasionally reluctant, storyteller. Gaiman explores his friend's sometimes-tortured relationship with creativity and deadlines, and shines a light on the lesser-known periods of Adams' life.

RELATED: Cover Reveal: See the Final Cover for Neil Gaiman's Don't Panic

In the passage below, Gaiman outlines the frustrating year Adams spent in Los Angeles in the early 80s, trying to ensure Hitchhiker's Guide would have a dignified transition from page to screen.

Read an excerpt from Don't Panic, and then download the book!

In 1979 Douglas was approached with an offer he found almost irresistible: a Hitchhiker’s film. All he had to do was sign a piece of paper, and he would have $50,000 in his hand. The only trouble was that what the director seemed to have in mind was “Star Wars with jokes”.

We seemed to be talking about different things, and one thing after another seemed not quite right, and I suddenly realised that the only reason I was going ahead with it was the money. And that, as the sole reason, was not good enough (although I had to get rather drunk in order to believe that). I was quite pleased with myself for not doing it, in the end. But I knew that we were doing it for TV anyway at that time.

RELATED: Fewer Than 42 Facts About Douglas Adams

"I’m sometimes accused of only being in it for the money. I always knew there was a lot of money to be made out of the film, but when that was the whole thing prompting me to do it, when the only benefit was the money, I didn’t want to do it. People should remember that."

[...]

A couple of years later, Terry Jones (of Monty Python, and a scriptwriter and director in his own right) decided that he would like to make a Hitchhiker’s film. The concept was to do a story that was based solidly in the first radio series, but pretty soon Douglas began to have second thoughts. He had done it four times (radio, theatre, book, record) and had recently done it for a fifth time (television), so decided that, in order to avoid the problems of repetition that would occur if he wrote the same script again (“I didn’t want to drag it through another medium—I was in danger of becoming my own word processor”), they would create a new story that would be “totally consistent with what had gone before, for the sake of those people who were familiar with Hitchhiker’s, and totally self-contained for the sake of those who weren’t. And that began to be a terrible conundrum, and in the end Terry and I said, ‘It would be nice to do a film together … but let’s start from scratch, and not make it Hitchhiker’s.’ Also, Terry and I have been great friends for a long time but have had no professional links*. And there’s a slight risk you take, when you go and do a professional job with a friend, that it might spoil things. So we didn’t do it.”

RELATED: Parrots, the Universe, and Everything: What Douglas Adams Learned from Traveling the World

Don't Panic author Neil Gaiman.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia CommonsIn 1982 Douglas went to California with John Lloyd to write The Deeper Meaning of Liff, and it was then that he was approached by two people with whom he got on extremely well, Michael Gross** and Joe Medjuck, about a Hitchhiker’s film.

At the time Douglas was excited by the possibilities of what could be done with computers, having seen some amazing special effects and technical work (imagine real computer graphics, done with computers!), and decided that he would write the film. He moved to Los Angeles, taking his girlfriend Jane Belson with him, bought a Rainbow word processor, and began to write.

Mike and Joe were producers working for Ivan Reitman, then known only for Animal House, now better known for 1984’s smash-hit Ghostbusters, and unfortunately there was not the same rapport between Adams and Reitman as there had been between Adams and the other two.

Douglas later described 1983 as a ‘lost year’. He and Jane hated Los Angeles, missed London and their friends. He found it hard to work, spending much of his time learning how to work a computer, playing computer games, learning to scuba dive, and writing unsatisfactory screenplays.

Transforming Hitchhiker’s into a film hit two snags. The first was that of organising the material: “There are inherent problems with the material. It’s a hundred minute film, of which the first twenty-five minutes are concerned with the destruction of Earth; then you start a whole new story which has to be told in seventy-five minutes, and not overshadow what went before. It’s very, very tricky, and I’ve had endless problems getting the structure right. With radio and television you have three hours to play with.

“The material just doesn’t want to be organised. Hitchhiker’s by its very nature has always been twisty and turny, and going off in every direction. A film demands a certain shape and discipline that the material just isn’t inclined to fit into."

The other problem was that Ivan Reitman and Douglas Adams did not see eye to eye on the various drafts of the screenplay. Again Douglas started using the phrase of “Star Wars with jokes”. Unfortunately this time he had already signed the contracts, was signed up as a co-producer, and had accepted amazingly large amounts of money to work on the film.

RELATED: 16 Must-Read Neil Gaiman Books

The versions of the script done in Los Angeles were attempts by Douglas Adams to meet Reitman half-way, of which he said, “They fell between two stools—they didn’t please me, and they didn’t please them.”

Los Angeles was getting Douglas more and more depressed. He began to feel he was losing touch with the very things that had made him write what he did anyway. Eventually he decided to leave.

“I didn’t realise how much I hated LA until I left. Then the floodgates opened, and everything came out. It wasn’t a good period for me, nor a productive period. I had a slight case of ‘Farnham’—that’s the feeling you get at four in the afternoon, when you haven’t got enough done. So there came a point when we all decided to disagree, and I’d come back to the UK where I felt more in touch, and try to get it right to my own satisfaction.”

Douglas returned to England, where he began to work once more on the screenplay of the film, in addition to beginning work on So Long, and Thanks for All the Fish and the Hitchhiker’s computer game.

At that time he told me, “What I’m trying to do with the film is use a completely different selection process to that which went into the TV series. We are trying to show the stuff you didn’t see in the TV series. So if you go back to the book, and find all the things not in the TV series … that’s the film!"

“Also, a lot of the film comes to have a completely different rationale. I’ve just put the scene with Marvin and the Battletank into the film, from the second book.”

For some years after, things appeared to progress very slowly, if at all, with the film seemingly stuck forever in Development Hell. Then suddenly, in January 1998, it was announced that the film was back on track and would be made by Disney.

Disney?

Well, actually Hollywood Pictures, a division of the mighty Disney empire. (Anyone who believes that Disney only make cartoons about talking animals should bear in mind that Pulp Fiction was made by a division of the company.) The success of Men in Black had made comedy science fiction flavour of the month, and Douglas had signed a deal with Hollywood Pictures which his agent Ed Victor summed up as, “substantial and special”. Jay Roach, who had made such a success of Austin Powers: International Man of Mystery and its sequel, was signed to direct, and Douglas professed himself very happy with both deal and director.

RELATED: 13 Books to Read If You're a Fan of American Gods

However, three years later the film was no closer to production, even though Douglas had actually moved to California to write the script. Occasionally, frustrating snippets of information about what was happening surfaced in interviews with Adams or Roach. Then, finally, Douglas announced that he had finished a draft of the script which really worked and everybody seemed to be happy with it.

That was in the Spring of 2001…

“* Terry Jones subsequently worked with Douglas twice: on a short story for The Utterly Utterly Merry Comic Relief Christmas Book, and on Starship Titanic.”

“** Gross was originally an artist and designer for National Lampoon, and was the man responsible for the famous cover showing a dog with a pistol to its “head, captioned “Buy this magazine or we shoot the dog!”

Want to keep reading? Download Don't Panic by Neil Gaiman today.

This post is sponsored by Open Road Media. Thank you for supporting our partners, who make it possible for The Portalist to celebrate the sci-fi and fantasy stories you love.

Featured photo of Adams in San Francisco in 2000: Wikimedia Commons