Superhero stories are everywhere — well, almost everywhere. TV screens? For sure. Movies? They’re basically the only tentpole movies left outside of Star Wars. And of course, comic books is their domain.

But books? Superhero novels seem to come few and far between. While there are certainly books where characters have powers, the actual trope of cape-wearing superheroes doesn’t happen all that much.

That’s why when I wrote We Could Be Heroes, I was a little worried about the marketplace. Yet about six months before release, I found out about Hench by Natalie Zina Walschots, which is a sharp, hilarious, and brutal novel examining the cost of superheroes through the lens of big data and analytics.

Though different in tone, both of our novels are equal parts love letters and side eyes to the world of superheroes. Natalie and I got to chatting about why we love superhero books, what they reflect in society, and much more.

Mike: Hench is such a fun, unique take on superheroes — where did the idea of using big data and analytics (which, really, is kind of the scourge of our modern society) to deconstruct superheroes come from? I have to think some of the discourse about the rampant destruction of Metropolis in Man Of Steel was part of the inspiration.

Natalie: It’s something that I’ve been preoccupied by and fascinated with for a very long time.

The moment you let yourself think about how much damage heroes are responsible for, you start counting, silently, in your head, and all of those great fight scenes and explosions suddenly come with a price tag, both material and human.

The more egregious the destruction, the easier it is to peer beyond the veil, but even relatively restrained heroes can cause a lot of damage.

RELATED: Authors Share How Apocalyptic Fiction Can Be an Antidote to Panic

Natalie: Something that leapt out to me about We Could Be Heroes is the way it focuses on the human cost, in terms of injury and trauma, that accompanies being a hero (or a villain). What was it that drew you to examining those vulnerabilities and consequences?

Mike: I think a lot of superhero media still has a firm definition of who is a hero and who is a villain. There may be underlying conflicting emotions or motivations, but usually by the midpoint, there’s a clear turn in one direction or another. Most of these are based on existing properties, so it’s kind of written into the characters’ DNA, but that leaves a lot of space to wonder what exists in between.

So that’s where my head starts: if you don’t have the epic stakes found in the DC/Marvel world, what would these characters actually be thinking and feeling? Would the superhero get fatigued from getting little thanks for breaking their body? Would the villain feel bad about hurting bystanders? Just how hard is it to live up to that persona, especially when other responsibilities or commitments tug at them?

These aren’t people with Bruce Wayne’s money or Professor X’s school, they’re just troubled people with powers and little money. That emotional and economic vulnerability makes for a lot of interesting conflict when you add superpowers.

RELATED: 10 Questions for Writers to Ask When Post-Apocalyptic Worldbuilding

Mike: Now in Hench, Supercollider, Electric Eel, Leviathan, and the rest of your cast are all riffs on established superhero/villain archetypes. What’s your own history with superheroes, and who are some of your favorites, past and present?

Natalie: I have always had a thing for villains. Even when I was a little kid, I loved them; I thought Captain Hook was actually the hero of Peter Pan, and wanted to know about his life and adventures much more than the Lost Boys. I joke (by which I mean joking-but-serious) that my sexual awakening occurred when I happened to see both the Phantom of the Opera and Labyrinth for the first time in the same summer.

I have identified powerfully with Harley Quinn since the first moment that I saw her on Batman: The Animated Series, and have been in love ever since. Her deep romantic friendship with Poison Ivy is also something I cherish. I have kind of a thing for Dr. Doom. What can I say, I am a sucker for a hypercompetent genius with a commanding presence and ego problems.

I’ve collected comics and been a fan of superhero stories for most of my life. Villains have, for me, always been much more interesting, captivating and complex characters. You can be a walking disaster area and still be a great villain, and that appeals to me a great deal.

RELATED: 7 Day-Saving Female Superheroes from Independent Comics

You clearly also have a deep love for superheroes, as well as what I think of as the superheroic support structures: all of the people who surround and uplift and work for heroes, without whom they wouldn’t be a tenth as remarkable as they are.

I’d love to hear about your relationship with sidekicks and other sources of heroic or villainous support (including henchpeople). Who are your favorites, and what draws you to these characters?

Mike: I love the secondary cast. They’re almost universally more interesting than the main hero. While I absolutely adore the CW’s DC shows, it usually has much more to do with the ensemble than the lead. And I think the biggest part of that stems from the role that the main heroes and villains are put into: they’ve got to be constantly saving the day or destroying the world, so they really have to stay in their lane most of the time.

But the sidekicks and hench have so much room for growth, so that leaves a lot of space to color in a character.

My favorite sidekick of all time is, of course, Harley Quinn. But she’s now a lead, both in film and on TV — so my new favorite sidekicks are from Harley’s TV series: the biggest cinnamon roll in King Shark, and the best amateur theater actor in Clayface. (I have such a crush on Ivy, but she's not a sidekick, she's a solo eco-terrorist.)

Still from Harley Quinn.

Photo Credit: Warner Bros. EntertainmentMike: So, when I was reading Hench, I kept thinking about how all of your characters are so much smarter and better at their jobs than Jamie and Zoe from We Could Be Heroes. My hapless duo would basically fail at everything in an epic crossover. What do you think your protagonist Anna’s take would be on them? Would she hire them?

Natalie: See, Jamie and Zoe didn’t strike me as people who were bad at their jobs, but people who had the wrong jobs. They both felt to me like they were stuck in positions where they didn’t fit, contorting their personalities (and bodies) in a desperate attempt to be who they (or people around them) felt they should be. I think when people get sorted as rigidly as they are (and as a lot of the characters in Hench are, though most of this happens offscreen), those roles are often ill-fitting.

I don’t think Anna would hire them for exactly the jobs they have in We Could Be Heroes, but I do think she would be very interested in trying to find out where they would thrive (which might be outside of the whole heroes-and-villains system altogether).

In both Hench and We Could Be Heroes, characters experience injury and recovery, albeit in very different ways. What was it about memory loss in particular that drew you in, and was it connected to the “hidden past” element to so many superhero stories?

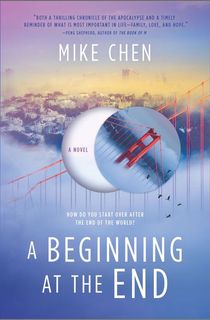

Mike: I’m always interested in the idea of nature versus nurture, and the idea of a tabula rasa reset. This was unintentionally a theme in all of my books so far; Here And Now And Then saw this in the form of a time-travel mishap, and A Beginning At The End saw the main characters actively using the pandemic to reset their lives.

With Jamie and Zoe, the added variable of superpowers is this accelerant that pushes this thought experiment into all sorts of directions. As characters, Jamie’s core is careful and methodical while Zoe’s is spirited and impulsive. We usually see that those are shaped by family, friends, culture, economics — but then you get this variable of having powers in a normal, grounded society. That’s fun to explore for characters.

Mike: There’s still not a lot of superhero prose out there, why do you think that is?

Natalie: Honestly, I don’t know why there isn’t more superhero prose. I think there should be. I think that superhero stories come with the expectation that they are profoundly visual narratives, whether that be in comics or as blockbuster movies. They still come with the expectation that they have to be loud, colorful and bombastic every single moment, and prose seems like an ill-fitting choice for that at first glance.

I think that this leaves huge swaths of material relatively unexplored, namely all of the weird and quiet moments that exist in superhero stories. I think prose is an excellent format for looking more deeply into the more human element of these stories, even when (especially when) you are dealing with superpowers.

On the flip side, though, in prose you can do literally whatever you want. You don’t have to worry about whether someone can draw what you described or whether the special effects budget can take it or if the game engine can handle the effect you want to achieve. You just get to make things up and describe it. So conversely, you can get so much stranger and more grand when the only limits you have are language.

RELATED: 8 Unforgettable Fantasy Books Featuring Heroic Women

Natalie: I think both of our books are about friendships, loyalty and trust just as much as they are about superheroes. What was it about these themes that made you want to explore them, and what is it about superhero stories that makes them such great venues for exploring intimate relationships?

Mike: I’m sure it says a lot about who I am as a person, but I think found family and deep honest friendship are among the most important things to me in the world. So not only is it personally very important, it also feels underrepresented in stories across media.

So much of our media focuses on romance between characters — there’s a reason why the standard three-act structure usually has a romance as a B-plot. But I think that true friendship is more valuable than most romances in our real world, and you rarely see that. I wanted to write a story about unlikely friends and what it took for them to build that trust.

To emphasize this, I wrote Jamie as pansexual, which meant that I wanted a romance to be theoretically possible, but both Jamie and Zoe have a clear internal moment of acknowledging that friendship is the right thing for them, not romance.

The superhero genre adds stakes to this, because at the core of friendship is trust. And when you’re dealing with the power to remove memories or a super-strong punch, the risks involved with trust are so much more heightened.

Okay, one last question. How about a recommendation for a superhero novel? We can’t say each other's!

Natalie: I’m going to have to go with V.E. Schwab’s Vicious and Austin Grossman’s Soon I Will Be Invincible. Yes that is two, but picking one favorite anything is literally my nightmare. I would much rather design a curriculum.

What about you, what is your superhero book recommendation?

Mike: Like we’ve mentioned, there’s not a ton out there. But my first pick was a huge inspiration on We Could Be Heroes, and that’s Daryl Gregory’s Spoonbenders. And it’s not technically superheroes, just powered people, but I’d recommend Fonda Lee’s Green Bone Saga (Jade City/Jade War/Jade Legacy) to anyone for its blend of 70s mafia movies and superpowers.

In fact, if you look closely in We Could Be Heroes, there’s a little shoutout to Fonda’s books, which means that a crossover event is always a possibility!

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.