When I was 8 years old I found a copy of Grimm’s Fairy Tales on our bookshelf. It was a very serious looking volume, but since it said “fairy tales” on the spine I figured it was a book for kids. Anyone familiar with the original tales collected in this book will laugh knowingly at this point. At eight years old, I had no idea.

Being an American kid growing up in the 80s with unfettered access to books and TV, I was familiar with the fairy tale canon. Evil stepmothers and bratty stepsisters and beautiful, put-upon girls who managed to escape such people once they caught the eye of a prince, or sometimes a king, who whisked them away to Happily Ever After. I thought that’s what I was getting with my serious bound book. Instead, I stumbled into a world of cruelty.

I mean, there were queens who danced to death in red hot shoes, stepsisters whose feet got mutilated and their eyes pecked out, and princes who got thrown into briar patches. Even the heroines of the stories didn’t always escape whole—one poor girl had her hands chopped off so she’d be a suitable bride for the Devil. I was confused and fascinated and eventually delighted by these darker tales. How come no one ever read me these?

Most people eventually come across a book or website with the original Grimm’s tales, or some other source of collected folk and fairy tales (Andrew Lang, Charles Perrault, etc.), and compare the stories to more modern versions—often with an unfavorable view of the latter. People often blame Disney for taking the teeth out of fairy tales and sanitizing them for Puritan sensibilities. But Walt isn’t the only culprit there: The Brothers Grimm did the same thing.

RELATED: 12 Enchanting Fairy Tales for Adults

Perrault’s Little Red Riding Hood is an explicit, cautionary tale about sexual assault, where the Grimm’s version is just a cautionary tale about leaving the path. Versions of Rapunzel that were told before the Grimm Brothers make it clear the prince and Rapunzel had sex and the resulting pregnancy is what gives her secret affair away to the witch. The brothers’ version elides over this fact and in the last little bit mentions some twins that came from a cabbage patch—but, of course, making sure it is known Rapunzel and her prince were married, so a child was not produced out of wedlock.

"This anthology made me realize how much sexist nonsense is embedded in the old tales we know and love."

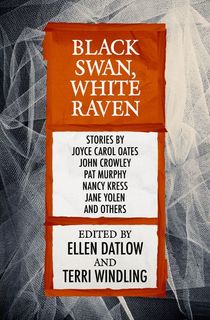

Even if we leave out the changes made for the sake of delicate sensibilities, folk tales always change. In the introduction to their anthology Black Swan, White Raven, editors Ellen Datlow and Terri Windling call the tales “shape-shifters.”

“… elusive, mysterious, mutable, capable of wearing many different forms. This fact is at the core of their power, and is the source of their longevity.”

Black Swan, White Raven is the first of the Datlow/Windling fairy tale anthologies I came across while haunting the science fiction and fantasy section of the bookstore. I was in college by then, and I hadn’t forgotten my love for the darker Grimm Brothers versions of folk tales. When I saw that this book was filled with new takes on the old stories, I bought it and dove in—expecting retellings with a modern twist. Once again, I had no idea what I was in for.

The stories in this anthology, and in all the others in this series, aren’t just darker or post-modern or irreverent. So many of the stories are about reclaiming women’s power in the realm of folk and fairy tale, about wrenching the narrative from the male gaze. They’re stories that make you question why the story you grew up with, even if it was the Grimm Brothers’ version, was ever considered the ‘norm’ to you—because clearly this is more accurate. This anthology made me realize how much sexist nonsense is embedded in the old tales we know and love.

RELATED: 10 Enchanting "Beauty and the Beast" Retellings

I have many favorites in this volume: Nalo Hopkinson’s Riding the Red, which brings the sexual innuendo at the core of the story firmly into the realm of the consensual; Steadfast by Nancy Kress, a story based on The Steadfast Tin Soldier that shines a light on everything wrong with men who will not leave you alone; and, Nina Kiriki Hoffman’s gorgeous poem The Breadcrumb Trail, that is better than any other Hansel and Gretel adaptation I’ve read—short or long form.

But the one I want to dive deep into is The True Story, by Pat Murphy. It’s a retelling of Snow White from the point of view of the stepmother queen. This kind of point of view shift is one our culture is now widely familiar with thanks to Wicked, Maleficent, and the TV series Once Upon A Time.

Back when the Datlow/Windling anthologies were first out (this particular anthology was published in 1997), shifting the viewpoint had not yet become a trend. Murphy does what we now expect of such stories: Recasts the “evil” stepmother in a sympathetic light—showing us the way it really was.

"When I went back to reread Black Swan, White Raven and revisit these stories, I was struck by how much further and deeper they go than almost any work I’ve seen or read in the years between."

On the way to doing this, The True Story also interrogates the foundations of many popular fairy tales and what’s behind all those evil stepmothers, evil queens, evil mothers-in-law, and other women of power and agency.

The queen loves her stepdaughter Snow White and dotes on her. She tells her stories, but not the same tales the queen was raised with where “the only thing that mattered about a princess was her beauty—she did not have to be clever or bold or strong.” Instead, she gives Snow White stories that allow her to understand that she can be clever and bold and strong.

The queen doesn’t send the child away because she is too beautiful. She sends her away because the king is a pedophile. Yes, that’s awful. Yes, that’s dark. But, as I said, this story is interrogating fairy tales, and Murphy’s queen rightly asks why people who believe that other version of the tale (the ones in which the king is alive) don’t ever wonder what the king was doing while the queen was sending the princess away and working her terrible spells? If the king was so good and the queen was so evil, why wasn’t the king protecting his daughter?”

And when Snow White is sent away, it’s not to a cottage in the woods occupied by seven men, it’s to a house full of older women who teach and care for the girl, and raise her to be strong and wise. Why would it have ever been seven men?

RELATED: 7 Fairy Tale Retellings That Will Make You Question Your Childhood

“In the stories, old women rarely play an important role—unless, of course, they are evil. Old women make evil potions, old women work black magic, old women envy the young and the beautiful, poisoning them, killing them, turning them into frogs. That’s what the storytellers say.”

Preach.

The Datlow/Windling fairy tale anthologies laid the foundation for the way we think about and retell and spin the classic tales today. Yet when I went back to reread Black Swan, White Raven and revisit these stories, I was struck by how much further and deeper they go than almost any work I’ve seen or read in the years between.

Even explicitly women-centered and arguably feminist retellings like Maleficent fall flat when it comes to the characterization and motivation of the protagonist. And when we do get a villain-as-heroine narrative with teeth, such as Elphaba in Gregory Maguire’s Wicked, the theatrical adaptation turns around and makes it a story about two women fighting over a guy.

I want to grab anyone in the midst of or thinking about retelling, adapting, rebooting, or otherwise mutating a Western folk tale for the screen, stage, or page, load Black Swan, White Raven and all the other books in this series into their eReaders, and lock them in a room until they’ve finished them all. Then they can have their computers and pens back. Since I don’t yet have this level of control (yet, being the operative word), I’ll settle for imploring you, dear readers, to revisit these books or read them for the first time.

K. Tempest Bradford is a speculative fiction writer by night, a media critic and culture columnist by day, and an activist blogger in the interstices. Her fiction has appeared in Strange Horizons, Electric Velocipede, and illustrious anthologies such as Diverse Energies. She’s also a regular contributor to NPR, io9, and books about Time Lords. Visit her blog: KTempestBradford.com

This post is sponsored by Open Road Media. Thank you for supporting our partners, who make it possible for The Portalist to celebrate the sci-fi and fantasy stories you love.