One phone call…

That’s all it would have taken to prevent the Space Shuttle Challenger accident. But no one made it on that bright, cold day years ago.

The result was catastrophic. Six career astronauts and one schoolteacher were killed. A billion-dollar space shuttle was lost and, as astronaut Franklin Chang Diaz later said, “We lost our innocence.”

The lives of thousands of other people were changed and, for a time, it was feared the entire Space Shuttle program could be cancelled.

It was my fortune to be in the Firing Room (the launch control room) at the Kennedy Space Center during the launch. I was the “Voice of Shuttle Launch Control,” so it was my voice that was heard around the world. But as protocol dictated, commentary was switched to the Johnson Space Center as the Challenger cleared the tower, and Steve Nesbit had the job of interpreting the conflagration in the sky. He could only say, “…obviously a major malfunction.” Despite multiple television shots and a room full of consoles monitoring every system and electronic spasm, that was about all anyone could have said at that moment.

Many months of investigation later, though, it became clear that one phone call could have prevented the accident. It could have been placed that morning to either Jesse Moore, NASA’s Associate Administrator for Space Flight, or Gene Thomas, the Launch Director. They were not told about a meeting at the Thiokol factory in Utah, which had built the solid rocket boosters. Every engineer in that meeting told their bosses that they should not launch Challenger in the freezing weather that had blanketed the Kennedy Space Center. The communication pipeline to these top managers had been plugged along the way by a few people who thought they were making the right decisions.

Either one of them, Moore or Thomas, could and would have postponed the flight, if they had had that information.

The "Challenger" broke apart 73 seconds after launch.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia CommonsThe biggest immediate problem that day was the cold. Cold is the enemy of elasticity. And elasticity of the thin “O” rings is what allows the segments of the massive solid rocket motors to seal in the thousand-degree gases that build up when they are ignited.

With the cold soak during the night before, the seals failed at ignition, a channel was created through the two-inch steel motor casing joint and then sealed by molten metal for about a minute. But at 73 seconds into the flight, a stream of fire had erupted from the rear joint and burned through a strut holding the solid motor in place. It pivoted outward and the top of the motor crushed the hydrogen and oxygen tanks on top of the External Tank, releasing their contents to ignite explosively in the inferno millions saw on television.

There was no escape mechanism for the crew.

Regardless of how sudden this may seem, there was warning: The seals had come close to failing before, and a program to fix the problem was underway. Despite that knowledge, the program had never set up a rule to prevent a launch when the temperature dropped below a certain temperature.

RELATED: Alan Shepard, the Apollo 1 Disaster, and the Race to the Moon

[Warning: Graphic footage.] Video: The live broadcast shown across the country as the Challenger departed from Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

Everyone I know who worked in the space program during that time felt a measure of guilt. Even many of the news outlets felt that if only they had done their jobs better they would have ferreted out the problems and might have prevented the accident.

So many lives were changed. People, of course, are the most important. The crew was made up of seven talented and accomplished individuals who never got to make their continuing contributions to the world.

Jon McBride, an astronaut who was training with his crew to command the next space shuttle flight, was diverted to NASA Headquarters as the Deputy Administrator for Congressional Relations. He probably would have gone on to command a number of other flights if not for the accident. Instead, he helped NASA secure continued federal funding, even though Congress had chipped away at the budget, so that the program could continue and we could build the amazingly capable laboratory known as the International Space Station.

Bob Crippen, who piloted the very first Space Shuttle and three more pioneering flights, was also diverted from his love of flying. He was scheduled to command the first launch of a Space Shuttle from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California later that year. That flight and all subsequent shuttle launches from the West Coast were cancelled.

Instead, Crippen played an important role in the accident investigation. Next, he went to NASA Headquarters to manage the shuttle program, served as Director of the Kennedy Space Center, and, after eventually retired from NASA to serve as President of Thiokol Propulsion Company—the company that built the solid rocket boosters for shuttle. Today, Thiokol, under the ATK banner, is building the solid motors that will take us beyond the moon and outward to Mars using the lessons from Challenger.

Carrying Department of Defense (DoD) payloads was one of the key components in making the Space Shuttle Program cost-effective. But after the Challenger accident, the DoD stopped flying its satellites and experiments on the Space Shuttle and went back to using ELVs—expendable (unmanned) launch vehicles—to this day.

After 133 successful flights, and two failures—including Challenger (1986) and Columbia (2003), the Space Shuttle Program formally ended in 2011. Today, progress is being made on a new, large rocket vehicle known as SLS (Space Launch System.) It is larger and more powerful than the Saturn V rockets that took us to the moon. Much of the infrastructure is in place at the Kennedy Space Center, and the crew module is being manufactured there as well.

Space is an unforgiving place to live and work. The Challenger and later the Columbia accident shook everyone in NASA to the core, but it didn’t shake their confidence in the future. I believe if you had surveyed the thousands of people who worked for NASA back in the early 1980s, 99 percent of them would have told you we would be sending people to Mars by the year 2000. The other one percent might have guessed closer to 2017.

After the accidents, the dates may have changed; but step-by-step we are getting ever closer to that goal. Mars will be followed by places we have not yet dreamed of. In the meantime, NASA will continue doing the research in science that will advance our understanding of our world and universe—making it a better place for all of us.

That’s what humans do.

About the Author

Hugh Harris

Photo Credit: Open Road MediaCalled “the Voice of NASA” for many years by the world’s television networks, Hugh Harris devoted 35 years with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration to telling the story of the United States space program. Although he is best known to the public for his calm, professional commentary on the progress of launch preparations and launch of the space shuttle, his primary accomplishments were in directing an outreach program to the general public, news media, students, and educators, as well as to business and government leaders. He also oversaw the largest major expansion (up to that time) in the history of the Kennedy Space Center’s visitor complex and tours.

This post is sponsored by Open Road Media. Thank you for supporting our partners, who make it possible for The Portalist to celebrate the sci-fi and fantasy stories you love.

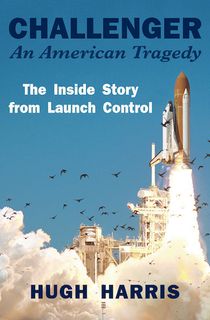

Featured photo of The Challenger being launched for its first mission in 1983: Wikimedia Commons