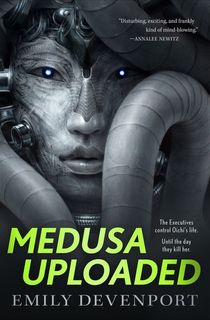

Full disclaimer: despite the plot line of Medusa Uploaded, I don't believe assassination is an effective way to eliminate classism. The French figured that out when they marched all of those people to the guillotine during their revolution, and just ended up with a new bunch of rascals in charge. But that doesn't mean we should shrug and say there's nothing we can do about it. At the very least, we need to recognize classism for what it really is.

If you want a nutshell-style definition of the results of classism, Joni Mitchell provided one is her song, “The Dinner Gong”, in which she laments that some get the gravy, some get the gristle, and some get nothing. It's an ism that encompasses a host of oppressions, including racism, sexism, ageism–take your pick of a very long list. But I believe that what lies at the heart of those cruel attitudes is one over-riding concept: Who is worthy?

RELATED: 10 Octavia Butler Quotes to Live By

Worthiness is a slippery idea. In American society, there's a mantra everyone tends to agree with: if you work hard, your work will be rewarded. No one likes to repeat that refrain more than the wealthy, powerful people who have no real grasp of the concept.

It's gaslighting of the highest order, because there's some truth in it. Hard work does tend to pay off, at least in some ways. But the people who work the hardest in this world are not the wealthiest people. The richest, most powerful people tend to be the ones who have benefitted from privileges. They tend to be white people who inherited wealth and who have access to networks of well-connected associates.

RELATED: Space Opera Meets Arrival in Samuel R. Delany's Babel-17

Intrepid individuals from all walks of life have managed to rise to the top without those privileges (or at least, without all of them). Those are the folks the fat cats like to point to when they're singing that song about how far hard work can take you. Once again, they have a point. But they also miss a point. People can succeed if they have some combination of skill, luck, talent, and perseverance. But the people who enjoy the most success in our world do so by investing much less effort. Yet somehow, these folks perceive themselves as being worthy of their success.

For most of my life, I have wondered what worthy meant. I naively assumed it had something to do with good characteristics: intelligence, courage, a fine grasp of ethics—that sort of thing. I thought maybe talent and perseverance were also qualities that made a person worthy of success. And I also concede that plenty of upper-class people have some or even all of those qualities. Being rich doesn't automatically make you a jerk. But my point is that being poor doesn't make you one, either. And that's what so many of us have trouble grasping, regardless of which class we belong to.

RELATED: 13 Classic Science Fiction Books Everyone Should Read

There's a Facebook meme that questions why America spends money on refugees when we have homeless veterans living on the streets here. The most obvious dog whistle is the one about immigrants, but I'm intrigued that only homeless veterans are worthy of our concern. That meme isn't trying to rile up wealthy people; it's aimed at working-class folks.

To me, this seems like a self-inflicted punch in the face. Quite a few working-class people believe that wealth is an indication of virtue; poverty is an indication of the lack of virtue. They continue to believe this despite the evidence that some of the wealthy people they admire the most are morally bankrupt.

For most of my life, the reasoning behind this escaped me. And then I read C. J. Sansom's Matthew Shardlake series, which is set during the reign of King Henry VIII, the time when a lot of the religious beliefs that define Protestantism began to take shape. One idea in particular caught my eye, the sermon about the spider suspended over the fire.

I first encountered this sermon in school. The gist of it is that what you do and what you feel doesn't matter in the long run. If God hasn't already deemed your spirit worthy, you're going to fall into the fire. Because your spirit is unworthy.

I didn't understand why anyone would think this sermon was upbeat. Frankly, it wouldn't have won me over as a convert. I didn't understand what it was implying until I looked at it in the light of American classism. A lot of us think wealth is a reward for spiritual worthiness. Regardless of how much people may stumble around in life, we think they're spiritually superior if God keeps rewarding them with wealth.

RELATED: Does Realism Matter When Creating a Fictional Magic System?

In Medusa Uploaded, the people at the top of the social food chain are the Executives. Their version of spiritual purity is the idea that they carry the genes of the original Great Clans who built their generation ship. They believe lesser classes on Olympia don't have that genetic purity, therefore they are less worthy of privileges. They turn out to be as wrong about that as we are (whether you're talking about DNA or spirituality).

I'm agnostic, and my perception of life is that it throws a lot of challenges at us. They form our characters. How we respond to those challenges defines us. To assume that bad things happen to people because their spirits are flawed is a harsh judgement, especially when you consider that most of the bad things that happen are inflicted by us, on each other and on ourselves.

RELATED: 10 Brilliant Hard Science Fiction Novels

So you can look at those deeply ingrained attitudes about worthiness, and conclude we'll always have some sort of class society, and there's nothing we can do about it. But we ordinary citizens have three kinds of power we can exercise. We can decide what information we can spread around. We can decide how we want to spend our money. And we can decide how to cast our votes. Those three powers are what the lower classes on Generation Ship Olympia are hoping to achieve–and we've already got them.

So shrug all you want. But remember what Aimee Mann sang: It's not going to stop 'till you wise up.

About the author:

Emily Devenport has written several short stories which appeared in Asimov's SF, Alfred Hitchcock Mystery Magazine, Clarkesworld, Uncanny, Cicada, and the Mammoth Book of Kaiju. Her day job is at the Heard Museum in Phoenix, Arizona. She is an aspiring geologist, an avid hiker and gardener, and a volunteer at the Desert Botanical Garden. Find her online at www.emsjoiedeweird.com or at @emdevenport.

Keep scrolling for more sci-fi stories!