There are a lot of variables to consider when developing a magic system for a game or a literary or cinematic series. Who is able to wield magic? What is the source of its power? How much training is required to become a magic-user? Does it involve incantations, material components, and/or specific gestures? Is it dependent upon details of time and place?

I had to consider all of those questions as I codified the rules for the fictional magic system used in my new Dark Arts novel series, but perhaps the most important question of all was this one: What are magic’s limitations? Knowing what magic could not do proved more important than trying to imagine everything for which it could be used.

RELATED: 8 Spellbinding Fantasy Books That Will Make You Believe in Magic

When I started developing Dark Arts, I was faced with conflicting desires. I wanted my series’ magic system to be grounded in the procedural, almost scientific methods of Renaissance-era ceremonial black magic, as codified by A. E. Waite in his early 20th-century tome The Book of Black Magic and of Pacts—a source that had served as one of the chief references of James Blish’s 1968 novel Black Easter, which in turn inspired my series. At the same time, I wanted my series’ depiction of magic to have the cinematic grandeur of J. K. Rowling’s bestselling Harry Potter books.

I could not have chosen two magic systems that had less in common if I had tried.

Rowling’s conception of magic is that it is accessible only to an elite few who must be born with an innate talent. They are trained as children at fantastical boarding schools, and their version of sorcery involves Latin gibberish coupled with dramatic flourishes of a wand. This is sufficient to unleash wondrous cascades of whatever the hell Rowling’s characters seem to want. It might strain credibility if transplanted into our real world, but damn is it fun to watch.

RELATED: 9 Action-Packed Sword & Sorcery Fantasy Books

Waite’s methods, which were faithfully dramatized in Black Easter, involve adult scholars who master a complex art through years of study and repetition. Its premise is that anyone literate and patient can likely master the Art, which is predicated upon the conjuring and control of demons, who serve as the source of all true magic. Because all magic depends upon striking soul-pacts with demons, it is a discipline to which only a fool or a sadist would subject children.

This latter approach to magic was the one that had captured my imagination when as a teen I first read Black Easter. It felt more “real” because of the rigor and precision it required, and the way in which Blish brought the demons and their terrible powers to life was truly chilling. That was the kind of magic I wanted for my series.

But it had a drawback: in Waite’s style of ceremonial magic, sorcerers (which he calls “karcists”) remain safely inside circles of protection when they send demons abroad to wreak havoc, gather information, procure treasure, or commit murder. If I stayed true to that aspect of the practice of magic it would be a more faithful representation of the Art, but it wouldn’t make for terribly exciting fiction. It is not a system of magic that lends itself to dramatic mage’s duels.

Still from The Two Towers.

Photo Credit: New Line CinemaConsequently, I struck a compromise between accuracy (which is a questionable virtue when one is dealing with something as far-fetched as demon-based sorcery) and entertainment value: on the advice of fellow author and veteran role-playing game designer Aaron Rosenberg, I added a new element to Waite’s rigorously documented system of ceremonial magic: a practice known as “yoking.”

Yoking is like reverse-possession. A karcist summons a demon with which she has a pact, and then the magician compels the spirit to bind itself to her mind and body. For as long as the mage can hold the spirit in thrall, she can wield the demon’s signature powers as if they were her own.

RELATED: 9 Sci-Fi and Fantasy Schools I'd Love to Attend

This gift of power comes at a cost: nightmares; nosebleeds; indigestion; insomnia; obsessive-compulsive behavior such as hair-pulling or self-cutting; etc. These and other grim side effects come bundled with each demon’s harnessed talent.

To quiet the infernal voices that haunt their thoughts, my sorcerers turn to alcohol, heroin, or whatever other vices can bring them solace—which means karcists who spend too long as battle-mages with yoked powers wind up as alcoholics, junkies, and brain-fried loons. This to me felt like a satisfying and potentially dramatic way to limit the power that any one sorcerer could wield without destroying himself.

This was something I considered vital to the system of magic, because without limitations, magic can easily run amok and take over a narrative. But reining in the potential of individual karcists was not going to be enough. So I made sure to spell out the many restrictions on magic’s uses and efficacy that one finds in Waite’s book as well as in Black Easter.

Still from SyFy's "The Magicians."

Photo Credit: SyFyBecause magic is about using demonic power to alter reality, part of which is created by the free will of others, using magic against those who are invested with popular authority—in particular, heads of state and other high-ranking elected government officials—is costly and difficult. Likewise, the more one asks of a demon, the more likely it is to balk at the order. Sending a demon to kill one person is de rigeur; sending one to assault an army is going to require sacrifices of absurd value by the karcist.

Setting these restrictions helped my magic system come alive at last. Knowing what it could do made it fun. Knowing what it couldn’t do finally made it seem real.

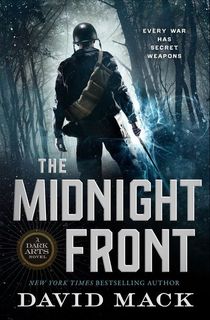

DAVID MACK is the New York Times-bestselling author of more than 30 novels, including the Star Trek Destiny and Cold Equations trilogies. His writing credits span several media, including television, film, short fiction, magazines, and comics. He resides in New York City.

Featured still from "Harry Potter" via Warner Bros.

.jpg?w=640)