Running a witchcraft shop in one of the most Pagan towns in Britain was not a childhood ambition of mine. I don’t think it occurred to me to aim that high. I did intend to become a writer, however—I blame the works of Lloyd Alexander and his fantastic evocation of an alternative Medieval Wales, with magic and fabulous beasts. I loved the Arthurian mythos, too, particularly The Matter of Britain.

On one family holiday, spent in Lyme Regis, we stopped off at a little town called Glastonbury, Avalon itself, on the way and visited the graves of Arthur and Guinevere. I was aware, in my early teens, that these probably weren’t actually their graves but a medieval marketing exercise to develop the town as a tourist trap, but this knowledge was so unromantic that I dismissed it forthwith and mooned over the green rectangle amid the silent honey-colored ruins beneath the Tor.

When I was 11 years old or so, my mother went to the local library and came back with a book, entitled Servants of the Wankh, by Jack Vance. Any double entendres related to vulgar British slang went right over our heads at that point. We both read it, and when we were finished my mother hotfooted it back to the library to get the rest of the series.

Thus were my joint loves of science fiction and fantasy born. I wrote throughout my teens, but this lapsed when I went to university and eventually finished my PhD thesis at Cambridge. Once that was out of the way, I turned back to my old love of science fiction, wrote a novel, wrote another one, wrote some short stories and, having gathered my courage to the sticking place, sent them off to magazines, where they were eventually published. Having acquired a wonderful agent, my first novel was published in 2000.

In 2005, several novels later, I was widowed. I was living in Brighton at the time, but my late partner and I often visited Glastonbury, as he had friends in the town. I didn’t intend to move there, but a year or so after his death, I did go back to Glastonbury and, during a wet afternoon, I went shopping and met a man in a witchcraft shop. The rest is history.

In late 2005, I packed up my Brighton flat and moved in with Trevor, in a little village just outside Glastonbury itself and in sight of the Tor. And I started running a witchcraft shop, too.

In due course, the witchcraft shop turned into two witchcraft shops, then three, plus an esoteric art gallery. Trevor and I took on a couple of young Voodoo practitioners as staff. We had many adventures, related in the two Diary of a Witchcraft Shop books that we wrote together. Our customers were witches, Wiccans, Heathens and Druids. We organized Pagan weddings and funerals. We ran training courses. We weren’t exactly Diagon Alley, but we were close.

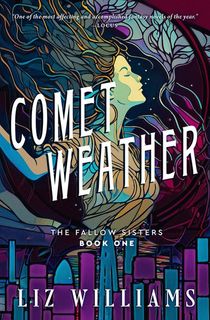

The Fallow Sisters

In addition to the shop itself, being in Glastonbury gives you plenty of ideas for fiction, but my vision for the Fallow Sisters novels was a little wider: I wanted these books to be set in the south of England, including London, and in Somerset, because Somerset contains more than Glastonbury and has full of legends of its own.

I drew on many of those legends, most notably, perhaps, those of the Wild Hunt. The leader of the Hunt, Gwyn ap Nudd, is said to live beneath the Tor, the curious hill with the ruined tower on top. From there, the Hunt rides out at numinous times of the year.

I know people who claim to have heard the Hunt, riding out of the mist. In the final book of the series, Salt on the Midnight Fire, the tales of Cornwall, of pirates and mermaids, feature. The goddess Elen plays a part in the London sections of the books and so does Austin Osman Spare, Southwark’s most famous magician of the early 20th century. (The Arthurian mythos itself has not featured greatly in this series of books so far, but watch this space).

Looking Forward

I have far more material than I can use. Although the Celtic countries are well-represented in fantasy fiction, England itself does not play quite such a major role, with the exception of London itself. It’s underused.

My influences, however, are the great fantasists of the early 20th century: Arthur Machen, John Masefield and Dion Fortune (herself a magician and a resident of both Glastonbury and London), as well as more recent writers—Susan Cooper is a notable example.

I plan to continue my southern English explorations, in both novels and short fiction—Avebury is the setting for some recent short stories, and the folklore of Dorset and the Jurassic coast is greatly neglected in fiction. So when people ask me where I get my ideas, the answer is simple: They come from where I live, from my home, and from my religion, because I am a Pagan myself.

And I have returned home. I was born in Gloucester, at the very edges of the South West (no one knows whether Gloucester counts as the Welsh Borders, or the South West, or the Midlands—but in truth it’s all of these places, so the old Roman city of my birth is itself geographically liminal). So the South West is familiar territory to me, from the merchant city of Bristol to the north, to Tintagel and beyond in the south.

My writing at the moment springs up from this landscape, from its myths and from the people who live here. The Fallow sisters contain elements of me—they are not me, but they are also like people I know. The house in which they live, magical Mooncote, is not my house—but its orchard is my orchard, its beehives are my beehives. I’m definitely not done with it just yet.