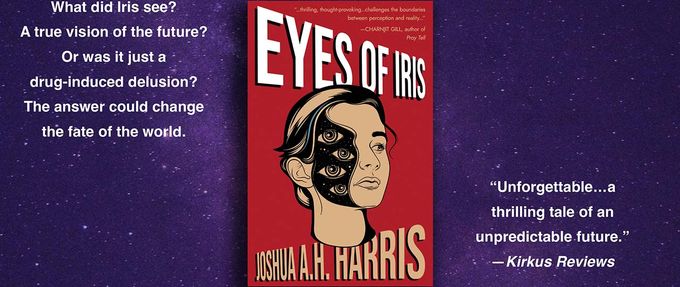

Is Iris really seeing visions of Earth circa 2300, or is she just having a bad trip on Ayahuasca? That's the question that psychiatrist Dr. Kairos asks himself in Eyes of Iris, which Kirkus Reviews calls a “an often thrilling tale of an unpredictable future.”

Inspired by works like The Time Machine by H.G. Wells and A Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy by Douglas Adams, Eyes of Iris offers a dark and dangerous vision of the future that will keep readers spellbound until the final page.

It's available at every major bookseller now, and you can try a sneak peek below!

Eyes of Iris Excerpt

FILE A.4

I awoke. As my eyes adjusted to my dark surroundings, I noted a series of thick wooden boards, about a foot above my face. For a second, I thought I was in a coffin. Death made sense given the black door. Perhaps Clara had murdered me? Or cast a spell? Maybe she was burying me alive.

Out of the corner of my eye, I noticed a strange wall to my right. I felt a thick blanket on top of me and realized I wasn’t in a coffin, but rather in a bunk bed—the bottom bunk, I presumed—shoved up against a stone wall. To my left, I perceived open darkness. The air was cool and dank, like I was in a cave.

As I lay there—frozen in that new stardust relative’s body and staring up at those oppressive wooden boards—I felt uneasy, worried. Wherever I was, it wasn’t home, and it didn’t feel right. I had no choice but to wait and see—and to hope I’d soon skip out of that experience. But something told me I wasn’t going anywhere anytime soon. This new circumstance felt more concrete, more hyper-tangible, than any of my other visions.

Some overhead lights flickered on. I heard multiple grunts—guttural protests, it seemed to me, neither animal nor human, from what I could surmise. The body of my stardust relative quickly turned away from the light before I could gather any other details about my surroundings. It curled up, facing the stone wall. More strange sounds began quietly echoing off the hard walls of what seemed to be a large—even cavernous—room.

Something felt off about that whole scene. I wanted to touch the stone wall. If I could just run my fingers across it, I’d know if this experience was real. The hard surface looked wet, but it might’ve just been worn smooth and slick by years of contact, like a flight of old stone stairs leading down into a medieval dungeon.

But I couldn’t move my hands. I recalled the rules—I couldn’t control my stardust relatives’ movements—and felt a moment of calm. This was just like the other visions. Perhaps I was in some long-forgotten prison in Russia or a mining camp in the High Sierra. I’d spend time here, observing, then I’d move on—with luck, very soon—toward home.

But then, as when you overcome the brief paralysis of waking from a deep sleep, a hand buried under the blanket—a hand that was previously outside of my realm of consciousness—became reality. I—the real me—twitched my right index finger. My heart raced as I registered the kinesthesia of that movement in my own brain, something that had never happened with any of my other stardust relatives. I gently flexed my other fingers and then lay still for a second to process the act that I might be more of an actor here, not merely a spectator.

I slowly drew my hand up and out of the covers and began to reach for the wall. But the instant my hand came into my field of vision, I froze, and my heart caught in my throat. My skin was gray, almost like an elephant’s hide, and the back of my hand was covered in short, black hair. My four fingers were elongated, approximately twice as long as normal—narrow, too, but muscular, with chapped knuckles—and my thumb was nearly as long as my fingers with an extra joint, like those people with triphalangeal thumbs.

I made a fist and opened my hand again, hoping to see a change, but everything remained the same. It felt like I was wearing a virtual-reality headset, playing some sci-fi game—only I was pretty sure this was reality-reality, or some version thereof. I gagged, almost threw up, but held it back; I had no idea where I was, when I was, or what I was.

I reached out, touched the stone wall, and was overcome by another wave of panic. I could really feel it—as though I was one hundred percent inside that body. The wall was as cold and hard as I’d imagined, but it wasn’t wet; its shiny appearance seemed to be the result of years of greasy skin rubbing against it.

I thrust my hand back under the blanket, pulled the covers over my head, and lay perfectly still. The darkness felt momentarily safe. My morning breath, on the other hand, smelled like death. The grumbling noises around me grew louder along with the sounds of feet shuffling. I prayed to every god that ever existed that I’d wake up somewhere else soon. But that was not to be.

FILE A.5

As I lay silent and still, I felt an itch on the bottom of my right foot. I instinctively reached my bizarre hand down my long, foreign legs and relieved the itch by scratching the heavily callused skin on the ball of my foot.

What I discovered, however, provided the opposite of relief: I only had three toes. They were wide, long, and powerful, like they could crush a small bird. I ran my fingers over my three thick toenails. Contrary to my normally well-maintained nails, the edges of these toenails felt thick, rough, and sharp, almost like talons. I wanted to scream, but I was afraid of making any noise. At that point, I remember thinking: there were never any human species with feet like these—this must be a hallucination.

But then, I clearly recalled Clara seated on the floor of her strange, warm living room, the palo santo smoke and the Ayahuasca ceremony, and the bitter, muddy taste of that strong, musky brew in my mouth. My unclouded awareness of that other world seemed to negate the idea that this was all in my head. Both worlds seemed equally real, equally crisp. I knew my old lie without any gaps—I could remember every detail—while at the same time, everything in that highly disturbing, bunk-bed reality felt entirely authentic: my new body’s strange, sickly-sweet odor; the odd coarseness of the blanket on my skin; and the awful furry, dry-mouth feeling on my teeth and tongue, like I hadn’t brushed in…well, maybe forever.

I ran my hands slowly up and around my bulging calves; the word “muscular” doesn’t even come close to describing them. My skin was stretched tight against the hard muscles and ropy tendons of these new legs of mine. Underneath, I could find no fat. As far as I could tell, I wore no clothes. My hands slid up to my ripped thighs and started to reach or the area you’d guess would be next, but before I could explore my alien genitalia, I suffered an immediate, mind-blowing headache.

In response to the excruciating pain, I pressed my rough palms into my eye sockets and squeezed my forehead with my long fingers. I’ve heard migraines can make people want to kill themselves; this pain felt worse than death. Maybe I was actually dying. I needed help, so I twisted toward the room and stuck my head out of the covers. All of a sudden, the pain turned to a dull ache, like a dial somewhere had been turned down. I learned later, that was, in a sense, exactly what had happened.

I took a moment to survey my surroundings. The area before me was more cave than room, though the floor was made of rough wooden planks, and dim, square lights set into the stone ceiling cast faint shadows all around. I’d been correct in thinking I was in a type of bunk bed, though the beds were stacked four high, one right on top of the next. Whoever constructed the bunks made them extra long and left just enough room to roll over, but not enough to sit up. I counted three rows of five—for a total of sixty beds. My bed was in the back corner, pressed against the wall.

The whole scene looked like a bizarre,windowless military barrack. All the bunks had already been vacated, except mine. I looked around and noticed a group of tall figures slowly walking away from me, gathering near a distant, open doorway.

Just then, my headache came back, and I felt an urge—I eventually began calling them conformity urges—to get out of bed. I threw the blanket off, stood up, and the headache instantly and completely disappeared. How could my head start hurting so intensely so quickly? And how could the pain stop so abruptly? It seemed physically impossible. Bile, with its sharp taste of alarm, rose from my stomach, coated my throat. My heart pounded in my ears. I again felt like I might be dying. Was I having a panic attack? I steadied myself against the bunk, closed my eyes, and tried not to pass out.

I took a deep breath. Then, in that strange way your mind reaches for old, reliable comforts in times of great need, I thought of Arthur Dent in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy—my favorite book of all time. The Ardmore Academy required all new students to read it upon admission. I was seven then. I read it repeatedly, backward and forward—a couple times upside-down. During my first semester, I even slept with my dog-eared copy under my pillow or comfort. Back then, Arthur Dent’s adventures into the unknown galaxy seemed a lot like my own lonely, strange journey—new town, new school, and many new, strange, and unreliable characters.

And now, standing in that mysterious cave-dorm, I felt like I’d been thrust into a completely different, but nonetheless equally mind-bending story. I recalled one quotation that I’d written in permanent marker on my canvas pencil bag, so long ago: “All you really need to know or the moment is that the universe is a lot more complicated than you might think, even if you start from a position of thinking it’s pretty damn complicated in the first place.” On the other side of my pencil case, I wrote the most famous quotation from that book in big block letters, “DON’T PANIC,” surrounded, of course—because I was still a little girl—by black-petaled daisies.

I opened my bizarre, new eyes and decided to take Douglas Adams’s advice; I’d resist panicking and try to embrace the complexity of this unanticipated turn of events.