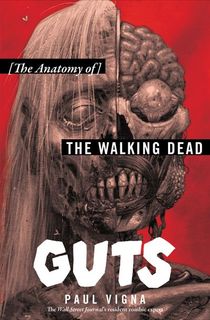

Paul Vigna may cover financial markets for the Wall Street Journal, but he’s also the publication's resident zombie expert—a title he's certainly earned with his newest book, Guts: The Anatomy of The Walking Dead. Vigna has been a devout follower of the television phenomenon since it premiered in 2010, writing weekly recaps in between bitcoin analyses.

His book, Guts, examines The Walking Dead from a critical perspective—and as a longtime zombie fanboy, he knows his stuff. From in-depth character studies and season breakdowns to explorations of the show’s cultural impact, Vigna dissects the series piece by piece as a zombie might tear its victims limb from limb (except Paul is, of course, incredibly nice). If you're a Walking Dead fan, the book is the baseball bat to your Negan.

Earlier this month, The Portalist sat down with Vigna at New York Comic Con to talk all things Guts, The Walking Dead, and how a zombie survival story became the most hopeful thing on TV.

We’ll start with how you came to the show. You tweeted that you saw the pilot episode and walked around New York City the next day like, “Is that person a zombie?” What was it about that first episode that you think really drew you in and caused such a visceral reaction?

I think that the first thing I probably responded to was just the writing and the craft that they put behind the show. That was a ninety minute pilot. You really didn’t see any zombies until the end. It was really about this story about this man who wakes up and the world is gone, and he’s trying to just get his bearings. But I thought, obviously, it was very well-done. It drew you in. It was very well-filmed, the acting was good, the writing was well-done. And I think it just fit the pacing of it—you know, the way they told that story and the reveal at the end when he gets into Atlanta, and for the first time they kind of draw you in with the story of him and it’s very kind of low key and then he gets to Atlanta and you see this explosion of zombies. And it was just, it was very well-crafted and, you know, I’m a zombie fan, a fan of the genre.

It came out before Game of Thrones—which I feel like everyone sort of credits for changing the way we view television. But, really, it was The Walking Dead.

Right. It didn’t. You and I know it didn’t!

RELATED: 10 Major Differences Between The Walking Dead Comics and the Show

You touched on something, too: It’s very much about the characters, and it’s always a character-driven story. Do you think that’s the reason why it has such a global appeal? Because it’s not just popular in America—it’s a phenomenon all over.

Yeah. I think that’s part of it. I think that’s a big part of it. You know, usually zombie shows and zombie movies are a very self-contained thing. You spend a little time with the characters, but not a lot of time. And by the end they’re usually dead, and the zombies have run amok. But this is a completely different story. The zombies are this persistent and present threat, but it really is about these characters ... But aren’t like normal comic book characters. They’re not superheroes, they don’t have super powers, they’re not mutants. They’re very relatable. They’re almost stereotypically average. You know, small town sheriff, battered housewife, unemployed redneck, pizza delivery boy, farmer, farmer’s daughter ... Everyone is very much an average person thrust into this outrageously enormous situation.

The whole story is how they deal with that, what it does to them psychologically. [It’s about] who manages to muddle through and survive, and who succumbs and can’t take it anymore and gives up. I think that’s something that people really relate to.

I always talk about how the show premiered in 2010, when the economy was bad. A lot of people’s lives had been ruined by the financial crisis in 2008 and 2009, and they were all trying to dig out of these extraordinary circumstances. So I think from the start, the fact that [The Walking Dead] was character-driven was important, but I think a lot of people—because of the situation we were all in—resonated with the characters and what they were dealing with. They identified with these characters on—and I swear to God this is not a pun intended—on a very gut level.

I appreciate all puns.

I didn’t mean it! I really didn’t mean it!

We’re able to see ourselves in these characters in another way—you explain this in your book—because zombies are metaphors. They’re a blank slate that we can project our own fears onto. Do you think the show is utilizing that? Somehow reflecting, maybe, our political climate, and our fears about that?

I think that ends up becoming part of the show, but I don’t think they write to that. Like you said, again, the zombies are blank slates, and there ends up being this amorphous fear and danger that you can graft onto. It’s whatever it is that’s stalking you in your real life. I think this show makes that possible, but I don’t think they necessarily write to that.

I know people have tried to figure out whether or not the show has a political point of view, and I’ve had people argue it passionately both ways. You know, “This is a terribly fascist show,” “this is complete socialism”—and I don’t think it’s either one. I think it’s just like all great art: There is a story that is told very well, and it’s left to the reader and the audience to interpret it. So I think people end up kind of putting onto the zombies whatever they want.

Horror seems to have this trend as of late ... Get Out tackled racism, and mother! is supposedly an allegory for how we mistreat the earth. Do you think The Walking Dead has some kind of overarching message?

Yes, but I don’t think [The Walking Dead] consciously set out to write a political show, or a social show. I think Kirkman was a fan of the genre, and he wanted to tell zombie stories, and he wanted to tell it in a serial format because he was trying to write a comic book. That was all he was trying to do. And he did it, and he did it very well.

Everything that you and I are talking about right now...I really think that is a product of the times in which the show came out. I think that it gets into what mass communication is all about, what television is all about. It really isn’t about this monolithic person over here delivering a message to you, the viewer. It is about someone trying to tell a story and to connect with the viewer—and then that’s only half the circuit. The other half is what the viewer gets, the viewers reaction, and what the viewer sends back toward the show. Within that circuit is where you start coming up with all these larger meanings for what is really going on. And I think the show is an example of that, rather than Robert Kirkman and Frank Darabont had a point of view and tried to tell it through zombies.

You also cover the financial markets of the Wall Street Journal, and write their [Walking Dead] recaps. How exactly did Guts come about?

There are two strands to it. The one strand is that, as a fan of the show—as an obsessive fan of the show—a lot of the things that ended up being in the book, I had been thinking about for a long time. I think as far back as 2013 I wrote an article about how this show reflects our difficult economic time. So I was thinking about it for awhile. But the real way it came about was I was having an email discussion with my agent talking. She said, really offhandedly, “Do you think you could do a book about The Walking Dead?” It was like ... I don’t know if you’re old enough to remember the V8 commercials, but it was like a V8 moment. I hit myself on the head.

I said, “Oh my God, of course.” I couldn’t believe I hadn’t even thought about it. So it was my agent’s idea. Her comment was something that crystallized all the thoughts I’d had in my head. And within a very short time I had sketched out the entire book. I knew exactly what I wanted it to be about and exactly what I wanted to say. Then we just took it out to all the different publishing houses.

What was your favorite thing [about the book], or the thing you were most excited to write about within the book?

Two things—and one kind of grew out of the other. There’s a whole chapter in there about going to a Walker Stalker convention. And I wanted to go so I could have that first person perspective and capture the fan experience—a lively way to illustrate the fandom. But it ended up actually becoming a much bigger thing than I thought. I got a lot more out of it because I was very surprised by how family-oriented it was and how many people brought their children there. At first, that seemed really odd to me—that parents would bring their children to a zombie festival.

I’d be really happy if my parents did that!

Yeah. But the more I was there, the more I talked to people, and the more I tried to discern why they [brought their children], the more I got to the heart of what people really, really love about this show. And what people really get out of [The Walking Dead] is the experience of living with these characters you love and identify with, but who are in constant peril and turmoil week after week, season after season...What I realized was that [the characters’] survival and this portrayal of them [their portrayals] end up giving a very rough template on how people can handle their own problems. And the simple answer is you just do not give up. You keep fighting.

I didn’t really realize that until I went to the convention. There’s a chapter in [Guts] called “Marcus Zurelius and Zombies.” And what I realized was that the show ends up really portraying—if you really want to know what the message of the show is—this extreme stoicism that you need to survive the worst of times...I think people see the way to handle the worst thing that could happen to you is to not worry about it, to not think about it. You know, there’s a scene where Rick gives this speech.

[SPOILERS]

There’s a scene where they’re in a barn and they’re physically and mentally exhausted. He gives this whole speech about his grandfather being in World War II and how is grandfather told himself every day that he was already dead. That was the only way he could face the war. And Rick says, “That’s how we survive. We tell ourselves that we’re dead. We do what we have to do, and then we get to live.” That is the heart of what this show is about: how you survive and you get through the worst—and that is by an extreme form of stoicism.

That crystallized at the convention, and I’m glad it did because that’s what I really wanted. That, to me, is the most important part of the whole show—and that’s what I really ended up wanting to write about. That is the message of the show. It ends up being very hopeful.

It is. Absolutely.

It’s terrible, it’s awful. People you love are going to have problems, but you can survive. And people get that message. The people at the conventions are very hopeful, and the vibe was so positive ... Ultimately, it becomes almost ironic that a zombie show is the most hopeful show on television, but it kind of is.

Do you have any plans in the future to write more about The Walking Dead, aside from your recaps?

No, but I have ideas. I mean, I would do more. It’s funny because you spend enough time with zombies and you start thinking up your own zombie stories.

Heck yeah!

So now I’m sitting around thinking about zombie stories. Maybe I’ll do my own zombie fiction.

What would you do in the event of a zombie apocalypse?

Oh yes. I’ve thought about this a lot. I know exactly what I would do. I may have mentioned it in [Guts]. I’m going to go to the library in my town. It is a big sturdy, brick building. It has a fireplace, so if I board up the windows, it’s defensible. I’ll have a source of heat, and in my town, at least, it’s right next to the police station, so I could pilfer the police station for supplies or weapons. And it’s a library—so if I need anything, if I need to figure out how to do something, I can look it up ... So I have knowledge, I have heat, I have shelter, I have the police next door. That’s where I’d go.

I think you’d make it.

I think I would make it too.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.