I’ve always liked to draw. I just don’t have any skill at it. I could manage some rough attempts at still lifes and such, but perspective and depth always defeated me. I remember showing a drawing of which I was inordinately proud to an old friend, one of SF’s top artists, to get his opinion. He looked at my effort and just smiled. That constitutes polite criticism.

It doesn’t matter anymore. Now we have multiple AI art programs that all seem to have appeared at once and can draw far better than any non-professional artists ever could. When I started experimenting with DALL-E, the program from Open AI (currently notorious for their writing program ChatGPT), I was flabbergasted by the results.

You input a stream of words, and in seconds, out pops four generations (as they call them). You can request mods on any one of the four, or try four new versions, and keep trying until you are satisfied, frustrated, or bored. The cost for this magic? Miniscule.

It's not quite as simple as it sounds, however, and the program is far from perfect. It has considerable difficulty with human bisymmetricality. In a rendering, one side of a person’s face often differs from the other. Sometimes the differences are subtle, sometimes insignificant, but all too often the result looks like bad surgery.

There also tends to be a profusion of digits. Six fingers on one hand, three on another, many often resembling sticks of wood more than human fingers, one finger (for no reason) more closely resembling a cephalopodian tentacle than a finger. The program renders landscapes and forests and such much more accurately. It all depends on the specificity of your written input, of course.

You can also request your renderings to be done as photorealistic, or digital art, or in the style of Picasso. Such experimentation is one of the delights of these programs.

For fun, I’ve been doing illustrations to several of my books. Midworld, Cachalot, Sentenced to Prism, and others (viewable on my Facebook fan page). The idea that I, with my limited-to-nonexistent drawing skills, could produce something like 20 full-color illustrations to Midworld over the course of a few days surely fits Arthur C. Clarke’s third law, which states, “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.”

What is more, the program’s inventions continually surprise me no matter what description or request I input. Some work well, some fall short, and some are downright amazing.

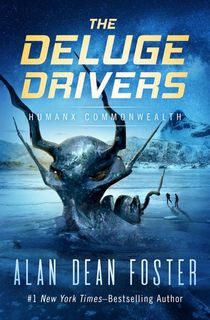

Occasionally I’ll get a request from a reader for an illustration to a certain story. One of these involved the Icerigger trilogy. In the course of having the AI produce its generations, it was suggested that I find one suitable for the Open Road cover to The Deluge Drivers.

Realize that all of this is so new that nobody has figured out quite how to react to it or what to do with it. Will such renderings replace actual artists? It pains me to say yes—but only to a certain extent. It’s a matter of time and money. If a corporation needs an illustration for a new ad, I don’t see one of the art AI’s able to include the number of specific changes required. It’s not that the programs lack “inspiration,” but there is a disconnect between what they can generate versus what a creative human mind can produce.

Of course, I’m talking about art involving people who can actually draw, or sculpt. Asking for something like “show a panda as a Jeff Koons balloon animal” will produce pretty much exactly what you anticipate. More detail requires more creative input.

Then there is the issue I mentioned earlier, where the AI falls apart when trying to render specifics. The solution to this lies in the use of software like Photoshop or GIMP to refine what the AI generates. I have neither of those programs and lack the necessary time to learn them. They are for professionals, or professional wannabes. But something as basic as a blur tool allows me to remove the most glaring errors in a generated image.

This was done with the image on the cover of The Deluge Drivers. Additional work was done in-house at Open Road to adjust the position of the two human figures, for example. So there is work for humans to adjust, polish, and fix even the best generations.

One thing I hope the speed of AI art allows for is the inclusion of illustrations in books (not just the covers) and particularly in ebooks. Not to mention that said illustrations can be “done” by the author. That way, a reader will know that the author completely approved of the final result whereas oftentimes illustrations or covers bear little relation to what the author had in mind.

Programs like DALL-E also allow for a new kind of interaction between author and art. I just finished a fantasy novel, Over There. For my own pleasure, I used the program to generate a number of illustrations for the story (also viewable on my Facebook page).

Seeing the final AI image, after I polished each of them as best I could with a blur tool, induced me to go back to the original manuscript and make some minor changes to it so that the prose would accord as closely as possible to the generated illustrations.

These changes in no way affected the story. But this back-and-forth is something new, and it’s a development that will only increase exponentially as more writers start meshing their words with their own generated art.

Next up? Authors using more advanced programs to make short films of their own work. Concerning programs like ChatGPT writing stories and novels … we’ll see. As for myself, as Clarke also said, “I’m vitally interested in the future because I expect to spend the rest of my life there.”

Featured photo: Michael Melford / alandeanfoster.com