Nichelle Nichols, the groundbreaking actress who portrayed Lieutenant Nyota Uhura on the original Star Trek, passed away July 30th, 2022 at age 89.

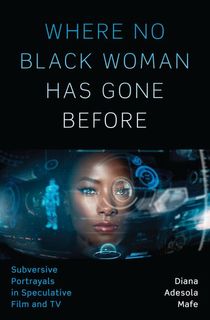

To honor Nichols' contributions to speculative fiction, we're sharing this excerpt from scholar Diana Adesola Mafe's book Where No Black Woman Has Gone Before. The 2018 work uses Star Trek's Uhura as a jumping-off point to examine not only "iconic but isolated twentieth-century examples" of Black women in SFF, but also on-screen speculative fiction representation in the new millennium.

Read on for an excerpt from Where No Black Woman Has Gone Before, then download the book!

According to Geoffrey Mandel’s apocryphal U.S.S. Enterprise Officer’s Manual, she was born on Stardate 1281 or, by the Gregorian calendar, January 19, 2233. But her other birthday (shared with her crewmates) is Tuesday, September 6, 1966, when she appeared for the first time on television sets across Canada on the network CTV (followed two days later by her American premiere on NBC). Hers was the first and sometimes only name people mentioned when they learned I was writing this book. And she is rightly considered an icon of the twentieth-century small screen. As an officer on a prime-time show about space exploration, she immediately symbolized change and possibility for black people, especially in the midst of the civil rights movement. Her ability to go where no black woman had gone before—outer space and, more literally, an empowered role on network television—made her a cinematic pioneer. Known only by her surname, at least in the original series, Lieutenant Uhura (Nichelle Nichols) was the solitary black female crew member of the starship Enterprise on the American cult classic Star Trek (1966–1969). And fifty years after her debut, she remains the symbolic face of black women in science fiction (SF) and a touchstone for fans and critics across cultures and generations.

RELATED: Explore the Final Frontier With These 10 Stunning Star Trek Books

In 1971, two years after the cancellation of Star Trek, Rosalind Cash starred as Lisa in Boris Sagal’s horror film The Omega Man. A savior and love interest for the white male protagonist, Robert Neville (Charlton Heston), Lisa embodies the Black Power aesthetics and politics of the day. After briefly appearing to Robert in a department store, she later materializes in a black turtleneck, red leather jacket, matching pants, and Afro to calmly point a gun at him and state, “All right, you son of a bitch, you just hold tight.” Despite appearing to abduct Robert, Lisa in fact rescues him from the mutated antagonists of the film. The two characters sustain witty banter for much of the narrative and quickly become friends and then lovers. Their interracial kiss is often cited as a groundbreaking moment in film, much as the 1968 kiss between Uhura and Captain Kirk (William Shatner) is hailed as a groundbreaking moment in television. The fact that both of these moments take place in the speculative genre says something about the potential of this genre to show viewers something new. The shortcomings of Star Trek and The Omega Man aside—most notably the reinforcement of white male authority at the expense of Otherness and a predictable eroticization of black womanhood—these examples put black women squarely on the speculative fiction map. Late-twentieth-century American speculative cinema subsequently produced a number of other memorable black female characters—Grace Jones as Zula in Conan the Destroyer (1984), Tina Turner as Aunty Entity in Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome (1985), Whoopi Goldberg as Guinan in Star Trek: The Next Generation (1987–1994), Angela Bassett as Mace in Strange Days (1995), and Alfre Woodard as Lily Sloane in Star Trek: First Contact (1996). This book is precisely about representations of black female characters in contemporary American and British speculative cinema and television. But my goal is to extend analysis of black women in this genre beyond iconic but isolated twentieth-century examples. Now that we have entered the new millennium (the same millennium in which futuristic narratives like Star Trek take place), are we seeing “new” representations of black femininity on the big and small screens?

Nichelle Nichols as Uhura on 'Star Trek.'

Photo Credit: CBSBy definition, speculative fiction implies limitless potential where raced and gendered imaginaries are concerned. The Oxford English Dictionary cites a 1953 remark by the American SF writer Robert Heinlein as a definition: “The term ‘speculative fiction’ may be defined negatively as being fiction about things that have not happened.” From a critical race and feminist perspective, imagining “things that have not happened” is not necessarily “negative” in a pejorative sense—it can be a very powerful and subversive act. Speculative fiction remains a contested label that is sometimes used as an umbrella term for the fantastical, the supernatural, and SF. It speaks to both utopian and dystopian possibilities and captures fiction on both the page and the screen. And while this genre has certainly been complicit in sustaining and even promoting social prejudices against Others, it has also been a remarkable site of possibility when it comes to interrogating and reinventing social constructs such as race, gender, and class. I use the term “speculative fiction” broadly and suggest that all of the case studies presented here constitute speculative fiction. Some lean more obviously toward SF in that they incorporate space travel, aliens, time machines, and so on. Others are gothic or fantastical but not necessarily SF. My approach is to treat SF as a subgenre of speculative fiction and to read all of my case studies as fictions that stretch the limits of imagination and plausibility.

This book examines four films, 28 Days Later (2002), AVP: Alien vs. Predator (2004), Children of Men (2006), and Beasts of the Southern Wild (2012), and two television series, Firefly (2002) and Doctor Who: Series 3 (2007). With the exception of AVP, which has been categorically dismissed by critics as a formulaic film with the sole purpose of generating new revenue from two celebrated franchises, all of these films and shows have received critical acclaim, whether as award winners, cult classics, or indie cinema.

Quvenzhané Wallis as Hushpuppy in 'Beasts of the Southern Wild.'

Photo Credit: Fox Searchlight PicturesThree of my case studies are British (28 Days Later, Children of Men, and Doctor Who), and three are American (AVP, Beasts of the Southern Wild, and Firefly). As such, they speak to questions of race, gender, class, nation, empire, and so on, in very different ways. Some of these works have generated a significant amount of academic interest. Children of Men, for example, has been hailed as “the first global blockbuster marketed as a teaching text” (Amago 212). The 2007 DVD edition includes commentary by a range of cultural critics, including Slavoj Žižek and Naomi Klein. A number of book-length studies and journal articles are dedicated to Firefly and the Doctor Who franchise, the latter being “the longest-running science fiction television series in the world” (Orthia 208). But 28 Days Later has received only sporadic scholarly attention despite its popularity, and Beasts of the Southern Wild has yet to generate any significant scholarship despite its polarizing reception as a “best” and “worst” film of 2012. Similarly, AVP has not triggered much academic discourse.

These case studies have never been read together or primarily through their representations of black femininity, but each one includes a black female character in its main cast. More importantly, the character in question—Selena (Naomie Harris) in 28 Days Later, Alexa “Lex” Woods (Sanaa Lathan) in AVP, Kee (Clare-Hope Ashitey) in Children of Men, Hushpuppy (Quvenzhané Wallis) in Beasts of the Southern Wild, Zoë Washburne (Gina Torres) in Firefly, and Martha Jones (Freema Agyeman) in Doctor Who—is arguably subversive. So this book is not intended to be a comprehensive survey of black women in Western SF cinema. Rather, I have tried to pinpoint the most compelling and critically complex examples of black female characters in new millennial British and American speculative film and television. This selection process is subjective, but these particular examples are crucial to a project like this one, or at least an excellent place to start.

Still from 'Children of Men.'

Photo Credit: Universal PicturesI do not address seemingly obvious blockbuster franchises such as The Matrix trilogy (1999 and 2003), the X-Men films (launched in 2000), and the rebooted Star Trek films (2009, 2013, and 2016) precisely because the black female characters are neither central nor especially nuanced. My strategic decision to explore only two television series also means that a number of speculative shows are not addressed, for example, Dark Angel (2000–2002), the rebooted Battlestar Galactica (2003–2009), The Walking Dead (2010–), Black Mirror (2011–), Once Upon a Time (2011–), American Horror Story: Coven (2013–2014), Sleepy Hollow (2013–), Z Nation (2014–), Sense8 (2015–), The Expanse (2015–), and Westworld (2016–). Most of these shows have memorable, even pivotal, black female characters, but addressing all of them is simply beyond the scope of this book. So I hope that other scholars with an interest in cinematic representations of black femininity will explore these titles and sustain this research.

Of course the new Star Trek franchise introduces Uhura, now played by Zoe Saldana, to a whole new generation of fans. And I will return to the new Uhura in my conclusion.

Want to keep reading? Download Where No Black Woman Has Gone Before below!

This post is sponsored by Open Road Media. Thank you for supporting our partners, who make it possible for The Portalist to celebrate the sci-fi and fantasy stories you love.