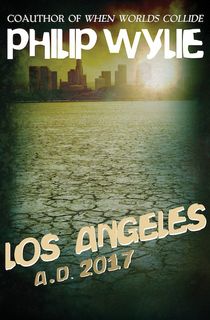

After being unconscious for forty years, magazine publisher Glenn Howard awakens only to find himself in the nightmare of all nightmares: America has been completely devastated by ecological disasters, and most of Earth’s population has been eliminated. Now, those who survived the catastrophe live beneath the wreckage of America’s major cities—controlled by greedy corporations.

The portrait that science fiction luminary Philip Wylie paints for us in Los Angeles A.D. 2017 is a terrifying one, albeit one that we, as a population, seem to be approaching. Our planet hasn’t been completely ravaged just yet, but Wylie’s illustration of 2017 doesn’t stray far from reality.

This prophetic read, ideal for fans of dystopian fiction and Orwellian-type storylines, will take you for a ride and leave you wondering whether our own ecological crisis can be reversed.

Read on for an excerpt of Los Angeles: A.D. 2017, and then download the book.

This is how the world ends.

Not with a bang but a whimper.

If T. S. Eliot had said nothing else in his strange and difficult verse, those two words would stick for a while: bang and whimper.

But the poet hadn’t said scream.

And the world hadn’t ended—quite.

Glenn gave himself over to an agony of self-reproach in the form of questions driven at his conscience:

Why didn’t we pay attention to the little warnings?

Why didn’t we act when we knew that the atmosphere of the earth, the waters, salt and fresh, and the land and the snows and ice of the poles were pervaded with DDT, mercury, radioactive elements?

Why didn’t we even attempt to find out what other planet-wide poisons were present and what combinations of all the half-million chemical compounds man knew he was dumping into his living space were adding to that awful sum?

Were we mad?

Why was I shown these examples of what so soon and so catastrophically followed my last day, there?

(I was on my way to use my power and influence to demand just that: a complete survey of what I had at last seen as a near-fatal state of the environment—which it proved to be!)

“Will they hold me accountable for the hideous sins of my era?

Is that why I had to bear these spectacles?

And were there more? Of course! She’d said as much! How many? Hundreds? Thousands? How many millions went to what kinds of screaming death, sacrifices to “progress?” “Technology?” “Civilization?”

What was that basically wrong with us all?

In the young woman’s absence Glenn wrestled with such self-queries. For he felt, knowing the consequences now—of all his generation, his establishment, the system—he felt forced to understand. It wouldn’t be possible, Glenn briefly felt—and then, in a rush, one answer came to him.

It was a strange one, new to Glenn and one that Glenn felt might serve, in some degree, at least, if he were made the villain-symbol, the whipping boy, for the terrible and nearly unanimous sin of his “civilization.”

The answer related to time.

He lifted his head from its mourning posture and his face showed a certain calm as Leandra returned.

This time, he didn’t ogle or erotically respond.

This time, his eyes merely noted her changed appearance and resumed their lucid but inturned shining.

“What is it?” she asked, softly, a little fearfully, and as if he might have lost his sanity in her short absence, unsure of him and his mind—well aware of the shock to which she had subjected him, on command.

“I was thinking,” Glenn replied, in a very steady tone, “that what you showed me had to happen.” He felt her negative reaction as a tensing of body, caught in an eye-corner. She stood in front of him and waited to recover some lost assurance. “It had to?”

“Yes. Why, Leandra? because of this; for a million years or more, from the time some species became our own, men were sufficiently intelligent to try to better their state, in a world that seemed utterly hostile, or all but that. We slowly managed, right? We made tools, captured fire, learned better and better ways to hunt, by cooperation, and to treat hides, polish stones and bones and bend wood for arms and implements and clothes. And at last we learned about seeds and agriculture, having already domesticated a few animals.”

Want more dystopian science fiction? Sign up for The Portalist's newsletter and get prophetic stories delivered straight to your inbox.

He waited for an answer, his eyes raised to hers. “Yes, Glenn. And thanks for that ‘Leandra’! Go on.”

“Not hard, and not much to add. Civilizations rose and vanished and left, or failed to leave, their added cultural discoveries. Thousands and thousands of years after the first field was planted and the first lasting ‘village’ of stone was erected—the ancestral city, call it—man began to gain in technology—though, for centuries and centuries his gains were pragmatic—windmills, water wheels, roads, carts drawn by horses, spinning, all the metalurgical steps, from, say, ancient Greece to about the 1600s. Even then, men had not actually commenced to be ‘scientists.’ “Up to then, the laws of nature on which the progress of man had been based were neither understood, nor widely, and not yet systematically, investigated. You with me?”

She seemed slightly impatient now—the watchglance to show it.

He ignored the signs and sat with little movement as he continued:

“About a century and a half ago, men began to be scientists, to look rationally into natural law. That was the start of the gigantic explosion which, actually, only became exponential and incomprehensible to men with the twentieth century. In the 1900s any decently educated man still understood the principles behind the technology he then had attained, steam power, locomotives, telegraphy, telephone, the first plane flights, high explosives and the weapons they led to, trolley cars and so on. But, as the next brief decades passed, scientific knowledge exploded until the parallel might be measured by the H-bomb, as greater than the A-bomb, and that, comapred to the prior explosives, TNT, dynamite, gun cotton—”

“I don’t see—” she interrupted. “And, anyway, we have to go to your place to dress, and then the Mayor’s home in a couple of hours. We’ll walk. You can tell me …”

So they entered the rather impressive square in front of the city hall, Glenn thought it was, and turned into a wider street than those he’d seen. There were people, all sorts, on the sidewalks and in the shops they passed. Small vehicles hummed by, going both ways, but not in numbers that would be called even “light” traffic, by Glenn’s scale.

For a time he was so full of his thought that he gave little attention to his surroundings. Novel, of course; but to Glenn, the novelties could be appraised later—while his insight had to be stated, as a way to firm it up and to test it.

“In America, as in all other civilized or ‘advanced’ nations, man’s knowledge and his applications of that for his technological wonders shifted humanity in one lifetime—from an understandable world to one so terribly complex and technically varied that hardly any one man was able to grasp the major concepts of science, the pure knowledge, that was applied to this period, one a single life could span. Do you see that?”

She said, “Of course. Not the part that seems to hit you so hard. We turn right at the next corner.”

“Well, maybe I can’t express it well enough. Though it’s simple. Humanity tried, for what seemed unarguable reasons, to ‘conquer nature’ and make human life less subject to natural menaces and calamities, from disease to crop-failure and the adversity of nature. Mankind actually began to achieve those goals of conquest, in his term, because he began to make use of his reason for scientific study, experiment, research and so gained truth-finding and knowledge-accrueal. When he had done that for about a century, the effort suddenly burst into every field of knowledge and produced concepts so valid that man’s understanding of such gains, for a million years and more, probably became impossible. Who, for instance, in 1913, could understand Einstein’s first theories? Who, next, understood what part of them, derived from that whole, underlay the atom bomb? How many people with color TV sets, in 1970 or ’71, could furnish you with a clear account of electro-magnetic radio propagation as it was applied to permit the building of their TV sets? Only those physicists, engineers and technicians trained to know. The rest of us were 99.999% ignorant, there.

“Or anywhere else. Who understood the medical advances? Who knew the mechanism of immunity, as of its state in 1971? Or the facts then known by geneticists?”

She guided him into a narrower and relatively darker street. “I get the point of the public ignorance. So what’s that meant to say?”

Want more dystopian science fiction? Sign up for The Portalist's newsletter and get prophetic stories delivered straight to your inbox.

This post is promoted by Open Road Media.Thank you for supporting our partners, who make it possible for The Portalist to celebrate the sci-fi and fantasy stories you love.

Featured photo: Liam Andrew / Unsplash