This March, we're celebrating the work of Joanna Russ, whose novels and nonfiction writing forever changed speculative fiction. Five of the late author's novels were released digitally in 2018 for the first time ever, after years in which her books were difficult to find.

Hailed by her contemporary Samuel R. Delany as “one of the finest—and most necessary” American fiction writers of her time, Russ was a vocal feminist. She used her platform as a scholar, critic, and author to illuminate sexism both within sci-fi stories themselves, and within the community of authors writing it.

Russ’ outspokenness made her and her work a source of occasionally vitriolic debate, so much so that, for better or for worse, ‘anger’ is the first word many associate with her.

In a 1973 letter to Russ, sci-fi author Alice Sheldon—who Russ knew at the time by the male pen name James Tiptree Jr.—put it perfectly:

“Do you imagine that anyone with half a functional neurone can read your work and not have his fingers smoked by the bitter, multi-layered anger in it?

“It smells revolutionary—no, wait, not “revolutionary.” Not the usual. It smells and smoulders like a volcano buried so long and deadly it is just beginning to wonder if it can explode. Fantastic anger.”

Anger is sometimes the only rational response. In a letter, Russ once wrote of a feminist critic "where is her anger?," adding "I think from now on, I will not trust anyone who isn't angry." If Russ herself was angry, well, she had a right to be. Her identity—as an out lesbian, as a feminist author, and as a critic—made her a target within the genre she loved so much. As she wrote to a friend in a 1994 letter, “I’m sure being an open lesbian has not been good for my career. Also doing all sorts of nonfiction feminist writing. I mean, put it together: book reviewer…feminist, lesbian highbrow—I’ve never made more than a $3,500 advance for any novel.”

Her controversial identity may have been why it took Russ five years to find a publisher for The Female Man, the 1975 Nebula Award finalist widely regarded as her fiction masterpiece. After the book was published, The Washington Post says, it “slid modestly into the world (and right out again) as a paperback original.’’ Today, it’s difficult to find copies, which is why a digital edition is so long overdue. The digital edition also includes “When It Changed,” a Nebula Award-winning and Hugo-nominated short story set in one of the worlds of The Female Man.

The novel follows four versions of Russ herself. There’s Jeanine, who lives in a dystopian America where the Great Depression never ended, in which women’s only opportunity for safety is through marriage. There’s Joanna, whose society is very similar to 1970s America. There’s Janet, who lives in Whileaway, an agrarian, women-only utopia whose inhabitants find romantic and sexual satisfaction with other women. Finally, there is Jael, who lives in a society where men and women are locked in a decades-long nuclear conflict.

In 1975, The Female Man’s structure was as unorthodox as its subject: it redefined what readers could expect from a sci-fi narrative. Its four worlds interweave unexpectedly, and the book is full of meta commentary. In it, Russ lays out how she expects the story will be perceived: as “shrill,” “aggressive,” and full of "the usual boring obligatory references to Lesbianism.”

RELATED: How Gay Is Your Geek TV?

These predictions were likely inspired by criticism she’d received in the past. For instance, in 1972, Russ published her story “When it Changed” and her essay “What Can a Heroine Do? Why Women Can’t Write.” Afterwards, the personal scrutiny around her work increased.

Helen Merrick’s essay “The Female Atlas of Science Fiction?,” included in the anthology On Joanna Russ, details how publications like the fanzine The Alien Critic became the center of a ‘flame war’ over Russ. The debate may have started with a particularly appalling letter from a reader who felt himself personally attacked by “When It Changed” and dismissed the story as the “sickening” work of a “bigot” full of hate because she "hasn’t got a prick."

His comments led to a flurry of responses from readers and established authors alike. Many of them, even when expressing support for Russ, still managed to depict her as a shrew and conveyed their dismay at her capacity for vitriol. For instance, in a 1974 issue of The Alien Critic, writer Philip K. Dick published an open letter to Russ, in which he wrote “Lady militants are always like Joanna, hitting you with their umbrella, smashing your bottle of whiskey—they are angry because if they are not, WE WILL NOT LISTEN.”

So Russ was no stranger to comments from all camps about her tone, her lifestyle, or her general respectability. These were, and in many ways still are, the lucrative costs of extrapolating science fiction to a step that one might assume would be natural for the genre. If sci-fi can envision new tech and new science, why would it be controversial for a sci-fi author to also envision new social structures and ways of relating to sex and gender?

Russ dared to write sci-fi where women are more than just hysterical victims or sex objects. In her 1972 essay "What Can A Heroine Do? or Why Women Can't Write,” she wrote that in fiction, women often “exist only in relation to the [male] protagonist. Moreover, look at them carefully and you will see depictions of the social roles women are supposed to play and often do play, but they are the public roles and not the private women; at their worse, they are gorgeous, Cloud-cuckooland and fantasies about what men want, hate or fear."

But Russ wrote women who were not centered in these male narratives: women who loved other women. Prophetic women, telepathic women, violent women. Women suddenly coming awake to the shortcomings of their world. Some of these stories, like her 1978 novel The Two of Them, are deeply unsettling.

The Two of Them follows Irene and Ernst, lovers and agents of the Trans Temp agency. The two have traveled across space and time to Ka’abah, a planet dominated by a patriarchal religion. Irene eventually realizes that Ernst has never truly been her ally, and that Trans Temp acquired her merely to appear more diverse. Struck by the ugly realization that, no matter what, men will always think women absurd and unreasonable, she violently takes matters into her own hands. It’s an unsettling, brutal ending that reverberates with anger—and may leave modern readers frustrated that the gaslighting Irene experiences is still common today.

RELATED: 10 Books Like The Handmaid's Tale

Her 1977 novel We Who Are About To... is similarly dark, and utterly gripping. It subverts expectations for the typical ‘lost in space’ narrative, informing readers in the opening line that there’s no hope for the stranded survivors of a spaceship crash: they are all going to die on this alien planet. Whereas other space adventure stories might follow a plucky hero colonizing a new world, in We Who Are About To... the unnamed female protagonist is the first to recognize and truly accept the fate alluded to in the book’s title.

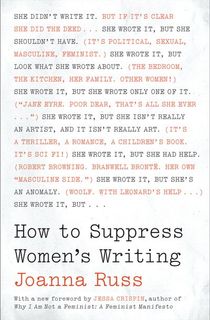

In truth, the breadth and scope of Russ’ fiction is too expansive to lay out here, except to say that her body of work was transformative stylistically and politically, and deserves to be read on a wider scale than it is today. And that’s not to mention her crucial and enduringly relevant nonfiction work, such as the 1983 book How to Suppress Women’s Writing, which clearly explains how women’s contributions to all walks of life are erased or undermined.

How to Suppress Women’s Writing breaks down the tactics used to suppress the work of women, and other marginalized identities, into a list of nine lies. It thrums with rhetorically-airtight anger—and will likely inspire anger in the readers who recognize that the methods used to devalue women decades ago may be even more relevant today.

As Hugo Award-winning author Kameron Hurley explains in her essay collection The Geek Feminist Revolution, How to Suppress Women’s Writing is essentially “the first internet misogyny bingo card.” Rather than feeling outdated 35 years after it was published, it instead feels eerily evergreen.

Thankfully, with the new release of these digital editions, Russ’ writing is a little less suppressed today than it has ever been. And the anger that sometimes propelled her work has a chance to continue to foment change. As Graham Sleigh writes in On Joanna Russ, “The challenge for readers now [...] is to see that her fierceness is necessary; that these battles have not been won and that, as always with letters, the onus is on the reader: what do you do now?”

Check out more great titles by Joanna Russ!

This post is sponsored by Open Road Media. Thank you for supporting our partners, who make it possible for The Portalist to continue publishing the stellar stories you love.

Featured photo via Alchetron and Photoshop

[Via On Joanna Russ, Kirkus Reviews, Tor.com's Reading Joanna Russ.]