As the iconic host of Reading Rainbow, as well as his podcast on which he reads short fiction, LeVar Burton has fostered a love of reading in generations of Americans.

What those of us who grew up with LeVar on our TV might not know is that he's not just a passionate reader—he's also an author himself.

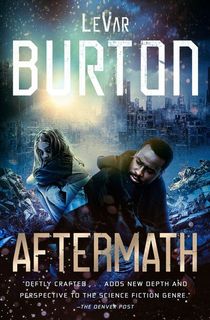

Burton's prescient debut novel, Aftermath, was first published in 1997, and is set in dystopian America after 2019. The country has been transformed by rapid scientific advancements, the assassination of the first Black president, a civil war, and cataclysmic natural disasters.

These predictions have gained new significance and plausibility since Aftermath was first published. But as Burton himself would say, you don't have to take our word for it: Burton's powerful debut is finally getting the re-release it deserves, featuring a brand-new foreword by the author.

The ebook and audiobook edition of Aftermath by LeVar Burton releases July 20th. To celebrate, we're sharing this exclusive excerpt from the Aftermath ebook. Take a look!

RELATED: Win a Copy of Aftermath Today!

Read on for an excerpt from Aftermath, and then pre-order the book!

Danger.

Dr. Rene Reynolds looked up, studying the faces of those who watched her. Twelve men and seven women, experts in the fields of science and medicine—most of them representing major medical corporations—sat on folding chairs and observed her movements with keen interest. She found no warmth in their faces, but she found nothing to indicate a threat of any kind.

Dismissing her feelings as nothing more than a case of pre-presentation jitters, she turned her attention back to the computers, EKG and biofeedback machines, checking gauges and adjusting knobs where necessary. Her hands trembled slightly as she connected several electrodes to the elderly woman lying on the examination table in the center of the room. The woman’s name was Irene McDaniels, and up until a few short weeks ago she had been suffering from both Parkinson’s disease and cancer of the colon.

Rene heard a chair squeak as one of the visiting doctors stood up. She watched out of the corner of her eye as he walked across the room to the folding table set against the wall. On the table were a coffeepot, cups, paper plates and a tray loaded with cookies and snack cakes. Most of those in attendance had already helped themselves to the goodies. Rene smiled inwardly. Part of being a good scientist was never missing out on a free meal.

Beyond the table, the blinds covering the windows had been drawn tight to keep out the harshness of the summer sun. Even then the antique air conditioner, which was powered by a row of solar panels on the building’s roof, had to struggle to do its job. The room was stuffy, and Rene felt a trickle of sweat leak down her back.

She couldn’t complain about the heat, however, for the Institute was the only building on the block to even have air-conditioning, and one of the few places to have electricity for more than a few hours a day. Electrical power was rationed, like a lot of other things. Fortunately, the city of Atlanta considered the Hawkins Neural Institute important enough to give them extra kilowatt hours. What they received from the city went to operate scientific apparatuses and medical equipment. Nonessential items, such as the air conditioner, had to share the trickle of power provided by the solar panels.

Turning back around, Rene noticed her reflection in the large mirrors that covered most of the opposite wall. The woman who stared back at her was a twenty-nine-year-old African-American who, up until a few years ago, had spent most of her life in the pleasant suburbs north of Atlanta. She stood a trim five foot seven, with long straight hair that was probably the hereditary result of her great-grandmother being full-blooded Cree Indian. During her transition into puberty, Rene’s hair had developed a somewhat shocking white streak.

Most women would have colored the streak, but Rene considered it a badge of honor, a symbol that she was different from most people. It was that feeling that drove her in life, causing her to strive for goals most never dreamed of reaching. Even as a teenager, when other girls were going on dates or hanging out, she had been busy setting in motion her plans for the future, determined to achieve greatness in her life and do something that would benefit all of mankind. Graduating high school with a 4.0 grade point average, she attended Duke University, earning a Ph.D. in neurophysiology. After college she came to work for the Institute, quickly becoming one of the company’s top researchers.

On a small cart beside the examination table, in a gray padded case, was the culmination of years of Rene’s hard work. Rene opened the case and removed a handheld micro-computer called the Neuro-Enhancer. Two thin cables connected the Enhancer to a copper headband lined with electrodes. Stretching the cables out, she carefully slipped the metal band on Irene McDaniels’s head.

Rene had spent years mapping the neural networks of the human brain, using everything from nuclear magnetic resonance scanners to high-speed computers to record the firing order of each individual neuron. Working closely with computer designers and electronic engineers, she had developed the Neuro-Enhancer. The device repeated neuron firing orders, but at an increased rate, sending tiny electrical impulses shooting through the hundreds of electrodes lining the inside of the copper headband.

She had been looking for a cure for Parkinson’s disease, which slowly destroys a tiny section of the human brain called the substantia nigra. It is the substantia nigra that supplies the neurotransmitter dopamine to a larger area in the center of the brain, called the striatum, which controls movement and motor skills of the human body. As dopamine supplies to the striatum dry up, movements slow and become erratic, eventually grinding to a complete halt. Although Parkinson’s disease is not usually fatal, many of those afflicted die from injuries suffered in falls. Others end up wheelchair-bound, unable to move or even speak.

After only a few weeks of testing with the Neuro-Enhancer, Rene noticed a remarkable transformation begin to take place in her patients. In almost every case the uncontrollable tremors of hands and legs, characteristics of the disease, were completely eliminated. Motor skills and muscle strength also returned. In less than three months, ninety percent of her patients were again walking and talking normally.

Excited over the prospect that she might have actually found a cure for Parkinson’s, Rene was absolutely stunned when she discovered that treatment with the Neuro-Enhancer also resulted in the elimination of chronic pain, an increase in memory and, probably the most important of all, the complete regression of cancer cells within the body. The regression did not stop when treatments were halted, but continued until the cancer was completely eliminated.

With sixty-five percent of Caucasians suffering from skin cancer due to a depleted ozone layer, and with the steady increase in the reported number of cases of carcinoma, leukemia, lymphoma and sarcoma in the general population, the country was on the brink of a major health collapse. Since the Neuro-Enhancer had proven effective in the battle against all types of cancer, it could just be the invention of the century.

Adjusting the metal band on Mrs. McDaniels’s head, Rene inserted a coded micro CD, containing neuron firing patterns, into the Neuro-Enhancer’s microcomputer. If the visiting scientists had come to see a show they were going to be disappointed. There really wasn’t anything to see. No flashing lights or fireworks, no lightning bolts coming out of the sky like in the old Frankenstein movies, nothing but a mild hum and the readout of the instrument gauges to show that the device was even working. Nor was the healing visible to the eye. Cuts did not vanish with the wave of a wand. Tumors and infections did not run screaming from the body.

The healing that occurred took days and weeks, not minutes and hours.

Rene flipped a switch on the computer console. On the wall behind her a projection screen lit up, displaying the readouts of Irene McDaniels’s pulse, blood pressure, EKG and biorhythm. She flipped another switch and a video movie appeared next to the readouts. The video showed Mrs. McDaniels as she was eight weeks ago: suffering from the advanced stages of Parkinson’s disease, barely able to walk or get out of a wheelchair, unable to feed herself or even speak clearly. Rene allowed the video to play uninterrupted for a minute, then turned to face her audience.

“Welcome, Doctors. I’m glad that you could be here today. Thank you for coming.” She picked up a small laser pointer and switched it on, aiming the tiny red dot of light at the screen. “The lady in the video is Mrs. Irene McDaniels; she is a patient of mine. These pictures were taken a little over two months ago. As you can see, Mrs. McDaniels suffered from Parkinson’s disease. Like many who are afflicted, she was no longer able to move about without the aid of a wheelchair. Nor could she feed herself or engage in normal conversation. Prior to coming to the Institute, she had been treated by several other doctors in the Atlanta area with a variety of different medicines, including levodopa. Unfortunately, what little relief the drugs provided proved to be only temporary.”

“What about fetal tissue implants?” someone interrupted. Rene turned and offered a slight smile. Even after thirty years, the implanting of brain cells culled from aborted fetuses into the striatum of a patient was still a controversial operation. Not only were moral issues raised, but surgeons often disagreed as to which of the two sections of the striatum should receive the implanted tissue. There were also debates about how much tissue was needed, how to prepare it for transplant, and whether to place large quantities in a few locations or small quantities in numerous locations.

Rene paused the video. “Fetal transplants were a possibility,” she said, nodding. “But if you look at the patient’s medical charts, in the folders handed out earlier, you’ll see that Mrs. McDaniels also suffered from colon cancer and was in poor physical health.”

She paused to allow time for the visiting doctors to check the charts before continuing. “Performing craniotomies on the surgical controls, as in fetal tissue transplants, can result in the formation of blood clots. Patients have also suffered strokes and heart attacks while undergoing such operations. Even if the surgery is a success there’s still the danger of side effects, such as respiration problems, pneumonia and urinary tract infections. With Mrs. McDaniels’s poor physical condition, I felt that such an operation would not be safe.”

She unpaused the video and fast-forwarded the film. The image of Irene McDaniels jerked and shook like a high priestess in a strange voodoo ritual. Rene slowed the action. “This footage was taken a little over two weeks ago.”

The video showed Irene McDaniels sitting at a table, writing a letter. Gone were the herky-jerky movements of her hands and head. Gone too was the unsmiling, unblinking facial expression typical of those who suffered from the disease. The last section of video, taken a few days ago, showed Mrs. McDaniels working in a backyard garden, pulling weeds, planting flowers and performing a host of tasks that should have been impossible for someone suffering from Parkinson’s. Rene looked away from the video screen to study the reactions of those in the room, amused at the stunned expressions on the faces of the visiting scientists.

“Bullshit. It’s a hoax,” someone in the back row whispered, loud enough to be heard. “The woman in the video is an actress.”

Rene stopped the video and shook her head. “I promise you that Irene McDaniels is no actress. If you look in the folders you will find complete medical reports from four of Atlanta’s top doctors. If Mrs. McDaniels is an actress, then she’s good enough to fool all four of them. She’s also talented enough to fake blood tests, X-rays and lab work. And as you can see by the reports, not only has she been cured of Parkinson’s disease, she has also been cured of colon cancer. Even the melanomas on her arms and the back of her neck have disappeared.”

She paused to allow the information to sink in. Several doctors flipped through the folders given to them, reading the day-by-day progress of five of Rene’s patients. The others stared intently at the charts displayed on the projection screen.

In the back row sat a large Caucasian man, powerfully built, his face and arms covered with a patchwork of dark brown skin grafts. Rene recognized the man, having seen his picture in numerous scientific journals. He was Dr. Randall Sinclair, one of the nation’s foremost authorities on the treatment of skin cancer. Dr. Sinclair made worldwide headlines three years ago when he invented “skin fusion,” a process of grafting skin from African-Americans, and other dark-skinned ethnic groups, onto Caucasians in order to increase skin pigmentation to stop the spread of skin cancer. The process was often effective, but it was very expensive and only the very wealthy could afford it.

The Neuro-Enhancer, on the other hand, was affordable and would be available to everyone. It was a cheap cure-all for the masses. With so many poor and dispossessed people dying from lack of even minimal health care, the Enhancer would go a long way toward bringing the country back together. If Rene never did another thing in her life, the Neuro-Enhancer would have made her existence meaningful.

RELATED: Win a Copy of Aftermath Today!

Want to keep reading? Pre-order Aftermath now!

This post is sponsored by Open Road Media. Thank you for supporting our partners, who make it possible for The Portalist to celebrate the sci-fi and fantasy stories you love.