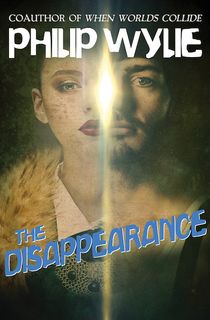

In an instant, two worlds are created: Men inhabit one, and women exist on the other. For Bill and Paula Gaunt, leading their lives separately in parallel dimensions is life-shattering. With the foundation of their universe in turmoil, they must reexamine who they truly are and struggle to survive in two different worlds.

Originally published in 1951, Philip Wylie’s The Disappearance was a groundbreaking study of gender roles set in a post-apocalyptic landscape. And while the novel provided a revolutionary look at equality, or lack thereof, the perceived differences between men and women in our society still ring true today.

Though many things have changed since the 1950s, some have not—women are still not seen as completely equal to men, in terms of career potential and compensation. Some of the ramifications of The Disappearance are quite possibly relevant today, even with the advances the world has made.

Told from alternating points of view, the novel starkly portrays what the struggle for survival would have been like in these worlds apart, as men and women realize the limitations placed on them by society’s conventional gender roles may prove deadly.

Paula Paula shook her head and thrust her hand into the peat moss to speed the wetting of the roots. She glanced at Bill’s windows and saw his silhouette. She wanted—she needed—his solace. A wretched day—the wretcheder because its miseries were mostly trivial. She was impelled toward her husband; but he was working. He wouldn’t like being interrupted by a sobby wife whose tears were caused by nothing new and nothing important and nothing that could be remedied. She pulled herself together with a strength she invariably summoned when things reached this low pitch. Typically feminine, she said furiously to herself, and it helped. But if Bill looks out, she thought, I’ll wave. And maybe he’ll come and talk; we’ve spent years talking about Edwinna to no purpose—but, at least—it’s better to share the shambles.

And she thought, with another momentary sag of her spirit, that the bright sun would certainly reveal the change in the shade of her hair—if Bill did look. She fought through a panicky instant of wanting to run away. It was replaced by a sudden assurance. Probably Bill had always known about the dye. Probably he understood, exactly, why pride and middle-aged anxiety made her try to keep it a secret. Probably he wouldn’t think it vulgar—funny, perhaps; or wistful.

For, after all, he loved her. She was sure of that.

Very sure and very much comforted. She gazed toward Bill again, ready to give a cheerful salute and a smile if he noticed her.

While she looked, Bill disappeared.

Paula ran into the house.

He was gone, all right.

Edwinna was sitting on the porch, still singing, watching Alicia patter about and waiting, in a false “sweet-mother-wife” pose, for her blind date to arrive.

Paula came out of the study and asked in a thin voice, “Did Bill leave his room?”

“No.”

“That’s what I thought! He just vanished!”

“Did you look in his bathroom?”

“Well—he didn’t come out—I’ve been here. And there’s only one door. So probably he simply evaporated.”

“Yes. That’s what he did.”

Now Edwinna looked up. “Mother. You’re pale as a ghost!”

Paula leaned against the edge of the maple-topped table where her collection of potted plants bloomed gaudily. “He must have thought of something, after all! He must have made some discovery! He must have been thinking, after all! Though it’s more the sort of thing Jim Elliot would do …!” She ran back through the study door and tensely addressed the empty room while Edwinna, and then Alicia came to watch.

“Bill!” she whispered. “Bill darling! Come back! Or say something!”

[...]

Bill

The Disappearance […] precipitated such a multitude of alarms and emergencies, which required swift action for the mere preservation of life, that nearly every man, as William Gaunt and his neighbors were soon to discover, was soon busied to the point of exhaustion.

At first, however, Gaunt continued to act from the inertia of his own personality and from private habit—as did innumerable other persons. The fact that so many did just that, preserved, through the early hours of crisis, a skeleton of familiar organization and behavior.

Firemen, although they could not immediately deal with all the sudden fires that ensued upon the vanishing of the women, went hooting and clanging to such fires as they could. The operators of “wreckers” rushed hither and thither through landscapes of smashed cars, setting back on the road whatever vehicles were usable and hauling others to repair shops. Emergency crews, frightened like all men about their loved ones, nevertheless hurtled to the nearest points of disaster and commenced to string new lines on telegraph poles, mend bridges, shut off gas mains, and the like. Habit, indeed, influenced even the most highly placed persons. It was later reported that the first question asked by the President of his hastily assembled Cabinet concerned the possible effect of the absence of all women upon the next elections.

Professors and teachers, in many cases, continued to hold (if not to instruct) classes suddenly and incomprehensibly reduced. Surgeons, inexplicably bereft of nurses, went on as best they could with operations. Ordinary laymen turned from the inexplicable to the salvage of boy babies who had been dropped onto floors and bare earth, down flights of stairs or into fishponds. The news reached embattled troops. Firing ceased on the earth’s face. Guerrillas fraternized with the enemy. Soldiers straggled from the line.

Gaunt, naturally enough, at first philosophized.

He walked up his drive, forgetting it was his intention to check his house for incipient perils. Unconsciously, he may have noted the absence of smoke or of ominous electrical humming and so dismissed that errand altogether. Certainly he was aware that a sense of tragedy and loss would sooner or later overwhelm him. But he was even more aware (at that point) of his possession of a mind both potent and unique and of the duty to bring it to bear upon the problem. Characteristically, he went to his study and, characteristically, he determined to jot down his thoughts in the form of notes. Tens, hundreds of thousands began diaries soon after the Disappearance and regular diary keepers continued to make their routine entries. But it is quite possible that Gaunt was the first man of all to do so after what the radio announcer had repeatedly called, in a fatuous, quasi-military fashion, “four-oh-five.”

At five-oh-five, or thereabouts, in his bold, tidy hand, Gaunt set down a fairly detailed description of the events to which he had just been witness and of his impressions. At some time after six, aware that the room had grown quite dark, he turned in his chair and switched on the lamp behind his back. The fact that it lighted and that its steady glow meant many things (such as, that the power plant in Cutler was operating and that the lines between his residence and the plant either had not been knocked down or had been repaired) never entered his head. He took the light for granted—at the moment. He was focusing the full powers of his mind elsewhere.

He had selected, to write in, a large “dummy” of blank pages bound in leather like a book—a handsome affair, a gift from the dean of Wake Forest College which Gaunt had saved for some special writing occasion. On the page he had numbered 16, he wrote: “Hypotheses.”

He sat awhile.

He underlined the word—and sat again, scowling. Finally, swiftly, he set down the following:

A) A nightmare. Objection: I respond to every test for being awake.

B) Insanity. Objection: None—in fact. No man can test himself for sanity. Intellectually plausible but emotionally unacceptable.

C) Mass hypnosis—mass, posthypnotic suggestion, and so forth. Objections: No hypnotist has ever been successful with the whole of any audience, even a small one; no person, group, or entity known on earth has access to everybody—I, for instance, have not listened to radio until this day for weeks, rarely read a paper, and so on; if the force of mind is here involved, it can hardly be human mentality.

D) Enemy action. Objections: Those above; also—what point if “enemy’s” own females also have vanished? If not, why did their radios cease, their women broadcasters fall silent at the critical moment?

E) A space-time, i.e., “physical” phenomenon. Objection: Again, none. Quiйn sabe? Certain legends, Rider Haggard’s She, William Sloane’s To Walk the Night, suggest imaginatively a bizarre connection between the conscious (or unconscious) entity of femaleness with mathematics, space, time, and the mystery involving these. No scientific material exists in respect to either the legends or the fiction.

F) Lysistrata. A trick, that is, learned by and disseminated amongst women to bring to heel the currently idiotic activities of men. Objection: Tenable as an idea but beyond the capacity of women to agree upon, to keep secret, and to perform unanimously and simultaneously.

G) Precedent, i.e., Elliot’s “Laecocidiaean women.” Objection: Never heard of them—or King Lestentum. More of Elliot’s probing into pseudo history, myth, intellectual balderdash.

H) God. Well?