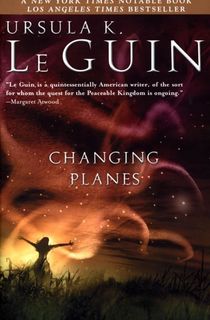

National Book Award-winning author Ursula K. Le Guin is known for her influential tales about worlds and cultures that are drastically different from our own.

In Le Guin's collection of fantastical short stories, Changing Planes, Sita Dulip is able to transport herself to fifteen societies not found on Earth. She does so by “changing planes.” After missing a literal plane, Sita passes the time in an airport by changing planes of existence as a form of escapism. She visits everything from a society that attempted to genetically engineer better life forms to one in which all but one family is descended from royalty.

The story “Social Dreaming of the Frin” takes Sita to the Frinthian plane—where dreams are public. Society dreams as a group, and it’s hard to escape for even one moment of privacy. People in close proximity to one another, such as those living in a city, all dream together—with often horrifying results. Frin is just one of the strange and sometimes humorous planes to be visited in Le Guin’s Changing Planes.

Read on for an excerpt from Changing Planes, and then download the book.

Social Dreaming of the Frin

NOTE: Much of the information for this piece comes from An Oneirological Survey on the Frinthian Plane, published by Mills College Press, and from conversations with Frinthian scholars and friends.

On the Frinthian plane, dreams are not private property. A troubled Frin has no need to lie on a couch recounting dreams to a psychoanalyst, for the doctor already knows what the patient dreamed last night, because the doctor dreamed it too; and the patient also dreamed what the doctor dreamed; and so did everyone else in the neighborhood.

To escape from the dreams of others or to have a private, a secret dream, the Frin must go out alone into the wilderness. And even in the wilderness, their sleep may be invaded by the strange dream visions of lions, antelope, bears, or mice.

While awake, and during much of their sleep, the Frin are as dream-deaf as we are. Only sleepers who are in or approaching REM sleep can participate in the dreams of others also in REM sleep.

REM is an acronym for “rapid eye movement,” a visible accompaniment of this stage of sleep; its signal in the brain is a characteristic type of electroencephalic wave. Most of our rememberable dreams occur during REM sleep.

Frinthian REM sleep and that of people on our plane yield very similar EEG traces, though there are some significant differences, in which may lie the key to the Frinthian ability to share dreams.

To share, the dreamers must be fairly close to one another. The carrying power of the average Frinthian dream is about that of the average human voice. A dream can be received easily within a hundred-meter radius, and bits and fragments of it may carry a good deal farther. A strong dream in a solitary place may well carry for two kilometers or even farther.

In a lonely farmhouse a Frin’s dreams mingle only with those of the rest of the family, along with echoes, whiffs, and glimpses of what the cattle in the barn and the dog dozing on the doorstop hear, smell, and see in their sleep.

In a village or town, with people asleep in all the houses around, the Frin spend at least part of every night in a shifting phantasmagoria of their own and other people’s dreams which I find hard to imagine.

I asked an acquaintance in a small town to tell me any dreams she could recall from the past night. At first she demurred, saying that they’d all been nonsense, and only “strong” dreams ought to be thought about and talked over. She was evidently reluctant to tell me, an outsider, things that had been going on in her neighbors’ heads. I managed at last to convince her that my interest was genuine and not voyeuristic. She thought a while and said, “Well, there was a woman—it was me in the dream, or sort of me, but I think it was the mayor’s wife’s dream, actually, they live at the corner—this woman, anyhow, and she was trying to find a baby that she’d had last year. She had put the baby into a dresser drawer and forgotten all about it, and now I was, she was, feeling worried about it—Had it had anything to eat? Since last year? Oh my word, how stupid we are in dreams! And then, oh, yes, then there was an awful argument between a naked man and a dwarf, they were in an empty cistern. That may have been my own dream, at least to start with. Because I know that cistern. It was on my grandfather’s farm where I used to stay when I was a child. But they both turned into lizards, I think. And then—oh yes!” She laughed. “I was being squashed by a pair of giant breasts, huge ones, with pointy nipples. I think that was the teenage boy next door, because I was terrified but kind of ecstatic, too. And what else was there? Oh, a mouse, it looked so delicious, and it didn’t know I was there, and I was just about to pounce, but then there was a horrible thing, a nightmare—a face without any eyes—and huge, hairy hands groping at me—and then I heard the three-year-old next door screaming, because I woke up too. That poor child has so many nightmares, she drives us all crazy. Oh, I don’t really like thinking about that one. I’m glad we forget most dreams. Wouldn’t it be awful if we had to remember them all!”

Dreaming is a cyclical, not a continuous, activity, and so in small communities there are hours when one’s sleep theater, if one may call it so, is dark. REM sleep among settled, local groups of Frin tends to synchronise. As the cycles peak, about five times a night, several or many dreams may be going on simultaneously in everybody’s head, intermingling and influencing one another with their mad, inarguable logic, so that (as my friend in the village described it) the baby turns up in the cistern and the mouse hides between the breasts, while the eyeless monster disappears in the dust kicked up by a pig trotting past through a new dream, perhaps a dog’s, since the pig is rather dimly seen but is smelled with great particularity. But after such episodes comes a period when everyone can sleep in peace, without anything exciting happening at all.

In Frinthian cities, where one may be within dream range of hundreds of people every night, the layering and overlap of insubstantial imagery is, I’m told, so continual and so confusing that the dreams cancel out, like brushfuls of colors slapped one over the other without design; even one’s own dream blurs at once into the meaningless commotion, as if projected on a screen where a hundred films are already being shown, their soundtracks all running together. Only occasionally does a gesture, a voice, ring clear for a moment, or a particularly vivid wet dream or ghastly nightmare cause all the sleepers in a neighborhood to sigh, ejaculate, shudder, or wake up with a gasp.

Frin whose dreams are mostly troubling or disagreeable say they like living in the city for the very reason that their dreams are all but lost in the “stew,” as they call it. But others are upset by the constant oneiric noise and dislike spending even a few nights in a metropolis. “I hate to dream strangers’ dreams!” my village informant told me. “Ugh! When I come back from staying in the city, I wish I could wash out the inside of my head!”

Even on our plane, young children often have trouble understanding that the experiences they had just before they woke up aren’t “real.” It must be far more bewildering for Frinthian children, into whose innocent sleep enter the sensations and preoccupations of adults—accidents relived, griefs renewed, rapes reenacted, wrathful conversations held with people fifty years in the grave.

Frinthian dreams.

Photo Credit: Houghton Mifflin HarcourtBut adult Frin are ready to answer children’s questions about the shared dreams and to discuss them, defining them always as dream, though not as unreal. There is no word corresponding to “unreal” in Frinthian; the nearest is “bodiless.” So the children learn to live with adults’ incomprehensible memories, unmentionable acts, and inexplicable emotions, much as do children who grow up on our plane amid the terrible incoherence of civil war or in times of plague and famine; or, indeed, children anywhere, at any time. Children learn what is real and what isn’t, what to notice and what to ignore, as a survival tactic. It is hard for an outsider to judge, but my impression of Frinthian children is that they mature early, psychologically. By the age of seven or eight they are treated by adults as equals.

As for the animals, no one knows what they make of the human dreams they evidently participate in. The domestic beasts of the Frin seemed to me to be remarkably pleasant, trustful, and intelligent. They are generally well looked after. The fact that the Frin share their dreams with their animals might explain why they use animals to haul and plow and for milk and wool, but not as meat.

The Frin say that animals are more sensitive dream receivers than human beings and can receive dreams even from people from other planes. Frinthian farmers have assured me that their cattle and swine are deeply disturbed by the visits of people from carnivorous planes. When I stayed at a farm in Enya Valley the chicken house was in an uproar half the night. I thought it was a fox, but my hosts said it was me.

People who have mingled their dreams all their lives say they are often uncertain where a dream began, whether it was originally theirs or somebody else’s; but within a family or village the author of a particularly erotic or ridiculous dream may be all too easily identified. People who know one another well can recognise the source dreamer from the tone or events of the dream, from its style. Still, it has become their own as they dream it. Each dream may be shaped differently in each mind. And, as with us, the personality of the dreamer, the oneiric I, is often tenuous, strangely disguised, or unpredictably different from the daylight person. Very puzzling dreams or those with powerful emotional affect may be discussed on and off all day by the community, without the origin of the dream ever being mentioned.

But most dreams, as with us, are forgotten at waking. Dreams elude their dreamers on every plane.

It might seem to us that the Frin have very little psychic privacy; but they are protected by this common amnesia, as well as by doubt as to any particular dream’s origin and by the obscurity of dream itself. Their dreams are truly common property. The sight of a red-and-black bird pecking at the ear of a bearded human head lying on a plate on a marble table and the rush of almost gleeful horror that accompanied it—did that come from Aunt Unia’s sleep, or Uncle Tu’s, or Grandfather’s, or the cook’s, or the girl next door’s? A child might ask, “Auntie, did you dream that head?” The stock answer is, “We all did.” Which is, of course, the truth.

This post is sponsored by Open Road Media. Thank you for supporting our partners, who make it possible for The Portalist to continue publishing the science fiction and fantasy stories you love.