The story of Mervyn Peake and his iconic Gormenghast books is both a triumph and a tragedy. Peake's three finished novels in the series, which begin with the 1946 publication of Titus Groan, are literary masterpieces. Some critics compare Peake's contributions to the fantasy genre with his more commercially successful contemporary, J.R.R. Tolkien.

If you think that's hyperbole, consider what Neil Gaiman wrote about the series: "There are no other characters in literature who live so visually in my mind as the inhabitants of Gormenghast. There are authors out there who have created moving, brilliant books, filled with characters who breathe and feel and love, true. There are authors who have made perfect, plangent sentences, some of which, I suspect, I will be able to recite long after I have forgotten everything else. Only Mervyn Peake paints in my head, using words as his medium. His creations live and breathe in our heads because we can see them. "

Doubtless, the vivid nature of Peake's vision can be attributed, at least in part, to his artist background. A portraitist and artist, Peake's unique style fills up the pages of the Gormenghast series. These illustrations help to add one more level of appreciation for the classic works.

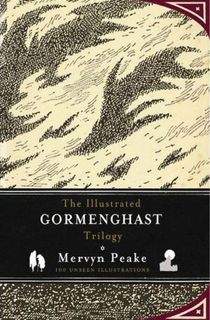

The Illustrated Gormenghast Trilogy

But where Tolkien told a masterful version of the classic hero's journey, Peake's tale was stranger, more twisting, and ahead of its time. The castle of Gormenghast is filled with courtly intrigue, family members scheming for power, and antiheroes rising to power. It's no coincidence that those themes are reminiscent of something like George R.R. Martin's A Song of Ice and Fire: Martin went so far as to name a minor character Titus Peake, which combines the name of the titular character, Titus Groan, with the book's author, Mervyn Peake.

Moreover, while readers were able to see the finished version of Tolkien's vision, fans of Gormenghast were forever left wanting. Peake suffered from early signs of dementia, making it impossible to complete his plans for the series. While he originally imagined Gormenghast as a long-running series, he did manage to publish three novels before his passing: Titus Groan, Gormenghast, and Titus Alone.

His wife, Maeve Gilmore, then took up the pen and created a fourth novel, focused as much on Peake's life as the world of Gormenghast in a title called Titus Awakes. A novella called Boy in Darkness, written by Peake, rounds out the list of Gormenghast titles.

Even unfinished as the series is, there is no denying the impact it has had on genre fiction. Peake's classic is worth celebrating, and in that vein, The Portalist is proud to present the first chapter of Titus Groan below. We hope you enjoy the odd cracking of Mr. Flay, the bizarre Hall of the Bright Carvings, and the distinct voice of one of fantasy's greatest authors.

From Titus Groan (Gormenghast Book 1)

Chapter 1: The Hall of the Bright Carvings

Gormenghast, that is, the main massing of the original stone, taken by itself would have displayed a certain ponderous architectural quality were it possible to have ignored the circumfusion of those mean dwellings that swarmed like an epidemic around its outer walls. They sprawled over the sloping earth, each one halfway over its neighbour until, held back by the castle ramparts, the innermost of these hovels laid hold on the great walls, clamping themselves thereto like limpets to a rock. These dwellings, by ancient law, were granted this chill intimacy with the stronghold that loomed above them. Over their irregular roofs would fall throughout the seasons, the shadows of time-eaten buttresses, of broken and lofty turrets, and, most enormous of all, the shadow of the Tower of Flints. This tower, patched unevenly with black ivy, arose like a mutilated finger from among the fists of knuckled masonry and pointed blasphemously at heaven. At night the owls made of it an echoing throat; by day it stood voiceless and cast its long shadow.

Very little communication passed between the denizens of these outer quarters and those who lived within the walls, save when, on the first June morning of each year, the entire population of the clay dwellings had sanction to enter the Grounds in order to display the wooden carvings on which they had been working during the year. These carvings, blazoned in strange colour, were generally of animals or figures and were treated in a highly stylized manner peculiar to themselves. The competition among them to display the finest object of the year was bitter and rabid. Their sole passion was directed, once their days of love had guttered, on the production of this wooden sculpture, and among the muddle of huts at the foot of the outer wall, existed a score of creative craftsmen whose position as leading carvers gave them pride of place among the shadows.

At one point within the Outer Wall, a few feet from the earth, the great stones of which the wall itself was constructed, jutted forward in the form of a massive shelf stretching from east to west for about two hundred to three hundred feet. These protruding stones were painted white, and it was upon this shelf that on the first morning of June the carvings were ranged every year for judgement by the Earl of Groan. Those works judged to be the most consummate, and there were never more than three chosen, were subsequently relegated to the Hall of the Bright Carvings.

Standing immobile throughout the day, these vivid objects, with their fantastic shadows on the wall behind them shifting and elongating hour by hour with the sun’s rotation, exuded a kind of darkness for all their colour. The air between them was turgid with contempt and jealousy. The craftsmen stood about like beggars, their families clustered in silent groups. They were uncouth and prematurely aged. All radiance gone.

The carvings that were left unselected were burned the same evening in the courtyard below Lord Groan’s western balcony, and it was customary for him to stand there at the time of the burning and to bow his head silently as if in pain, and then as a gong beat thrice from within, the three carvings to escape the flames would be brought forth in the moonlight. They were stood upon the balustrade of the balcony in full view of the crowd below, and the Earl of Groan would call for their authors to come forward. When they had stationed themselves immediately beneath where he was standing, the Earl would throw down to them the traditional scrolls of vellum, which, as the writings upon them verified, permitted these men to walk the battlements above their cantonment at the full moon of each alternate month. On these particular nights, from a window in the southern wall of Gormenghast, an observer might watch the minute moonlit figures whose skill had won for them this honour which they so coveted, moving to and fro along the battlements.

Saving this exception of the day of carvings, and the latitude permitted to the most peerless, there was no other opportunity for those who lived within the walls to know of these ‘outer’ folk, nor in fact were they of interest to the ‘inner’ world, being submerged within the shadows of the great walls.

They were all-but forgotten people: the breed that was remembered with a start, or with the unreality of a recrudescent dream. The day of carvings alone brought them into the sunlight and reawakened the memory of former times. For as far back as even Nettel, the octogenarian who lived in the tower above the rusting armoury, could remember, the ceremony had been held. Innumerable carvings had smouldered to ashes in obedience to the law, but the choicest were still housed in the Hall of the Bright Carvings.

Illustration by Mervyn Peake

This hall which ran along the top storey of the north wing was presided over by the curator, Rottcodd, who, as no one ever visited the room, slept during most of his life in the hammock he had erected at the far end. For all his dozing, he had never been known to relinquish the feather duster from his grasp; the duster with which he would perform one of the only two regular tasks which appeared to be necessary in that long and silent hall, namely to flick the dust from the Bright Carvings.

As objects of beauty, these works held little interest to him and yet in spite of himself he had become attached in a propinquital way to a few of the carvings. He would be more than thorough when dusting the Emerald Horse. The blackand-olive Head which faced it across the boards and the Piebald Shark were also his especial care. Not that there were any on which the dust was allowed to settle.

Entering at seven o’clock, winter and summer, year in and year out, Rottcodd would disengage himself of his jacket and draw over his head a long grey overall which descended shapelessly to his ankles. With his feather duster tucked beneath his arm, it was his habit to peer sagaciously over his glasses down the length of the hall. His skull was dark and small like a corroded musket bullet and his eyes behind the gleaming of his glasses were the twin miniatures of his head. All three were constantly on the move, as though to make up for the time they spent asleep, the head wobbling in a mechanical way from side to side when Mr Rottcodd walked, and the eyes, as though taking their cue from the parent sphere to which they were attached, peering here, there, and everywhere at nothing in particular. Having peered quickly over his glasses on entering and having repeated the performance along the length of the north wing after enveloping himself in his overall, it was the custom of Rottcodd to relieve his left armpit of the feather duster, and with that weapon raised, to advance towards the first of the carvings on his right hand side, without more ado. Being on the top floor of the north wing, this hall was not in any real sense a hall at all, but was more in the nature of a loft. The only window was at its far end, and opposite the door through which Rottcodd would enter from the upper body of the building. It gave little light. The shutters were invariably lowered. The Hall of the Bright Carvings was illumined night and day by seven great candelabra suspended from the ceiling at intervals of nine feet. The candles were never allowed to fail or even to gutter, Rottcodd himself seeing to their replenishment before retiring at nine o’clock in the evening. There was a stock of white candles in the small dark ante-room beyond the door of the hall, where also were kept ready for use Rottcodd’s overall, a huge visitors’ book, white with dust, and a step-ladder. There were no chairs or tables, nor indeed any furniture save the hammock at the window end where Mr Rottcodd slept. The boarded floor was white with dust which, so assiduously kept from the carvings, had no alternative resting place and had collected deep and ash-like, accumulating especially in the four corners of the hall.

Having flicked at the first carving on his right, Rottcodd would move mechanically down the long phalanx of colour standing a moment before each carving, his eyes running up and down it and all over it, and his head wobbling knowingly on his neck before he introduced his feather duster. Rottcodd was unmarried. An aloofness and even a nervousness was apparent on first acquaintance and the ladies held a peculiar horror for him. His, then, was an ideal existence, living alone day and night in a long loft. Yet occasionally, for one reason or another, a servant or a member of the household would make an unexpected appearance and startle him with some question appertaining to ritual, and then the dust would settle once more in the hall and on the soul of Mr Rottcodd.

What were his reveries as he lay in his hammock with his dark bullet head tucked in the crook of his arm? What would he be dreaming of, hour after hour, year after year? It is not easy to feel that any great thoughts haunted his mind nor – in spite of the sculpture whose bright files surged over the dust in narrowing perspective like the highway for an emperor – that Rottcodd made any attempt to avail himself of his isolation, but rather that he was enjoying the solitude for its Own Sake, with, at the back of his mind, the dread of an intruder.

Illustration by Mervyn Peake

One humid afternoon a visitor did arrive to disturb Rottcodd as he lay deeply hammocked, for his siesta was broken sharply by a rattling of the door handle which was apparently performed in lieu of the more popular practice of knocking at the panels. The sound echoed down the long room and then settled into the fine dust on the boarded floor. The sunlight squeezed itself between the thin cracks of the window blind. Even on a hot, stifling, unhealthy afternoon such as this, the blinds were down and the candlelight filled the room with an incongruous radiance. At the sound of the door handle being rattled Rottcodd sat up suddenly. The thin bands of moted light edging their way through the shutters barred his dark head with the brilliance of the outer world. As he lowered himself over the hammock, it wobbled on his shoulders, and his eyes darted up and down the door returning again and again after their rapid and precipitous journeys to the agitations of the door handle. Gripping his feather duster in his right hand, Rottcodd began to advance down the bright avenue, his feet giving rise at each step to little clouds of dust. When he had at last reached the door the handle had ceased to vibrate. Lowering himself suddenly to his knees he placed his right eye at the keyhole, and controlling the oscillation of his head and the vagaries of his left eye (which was for ever trying to dash up and down the vertical surface of the door), he was able by dint of concentration to observe, within three inches of his keyholed eye, an eye which was not his, being not only a different colour to his own iron marble but being, which is more convincing, on the other side of the door. This third eye which was going through the same performance as the one belonging to Rottcodd, belonged to Flay, the taciturn servant of Sepulchrave, Earl of Gormenghast. For Flay to be four rooms horizontally or one floor vertically away from his lordship was a rare enough thing in the castle. For him to be absent at all from his master’s side was abnormal, yet here apparently on this stifling summer afternoon was the eye of Mr Flay at the outer keyhole of the Hall of the Bright Carvings, and presumably the rest of Mr Flay was joined on behind it. On mutual recognition the eyes withdrew simultaneously and the brass doorknob rattled again in the grip of the visitor’s hand. Rottcodd turned the key in the lock and the door opened slowly.

Mr Flay appeared to clutter up the doorway as he stood revealed, his arms folded, surveying the smaller man before him in an expressionless way. It did not look as though such a bony face as his could give normal utterance, but rather that instead of sounds, something more brittle, more ancient, something dryer would emerge, something perhaps more in the nature of a splinter or a fragment of stone. Nevertheless, the harsh lips parted. ‘It’s me,’ he said, and took a step forward into the room, his knee joints cracking as he did so. His passage across a room – in fact his passage through life – was accompanied by these cracking sounds, one per step, which might be likened to the breaking of dry twigs.

Rottcodd, seeing that it was indeed he, motioned him to advance by an irritable gesture of the hand and closed the door behind him.

Conversation was never one of Mr Flay’s accomplishments and for some time he gazed mirthlessly ahead of him, and then, after what seemed an eternity to Rottcodd he raised a bony hand and scratched himself behind the ear. Then he made his second remark, ‘Still here, eh?’ he said, his voice forcing its way out of his face.

Rottcodd, feeling presumably that there was little need to answer such a question, shrugged his shoulders and gave his eyes the run of the ceiling.

Mr Flay pulled himself together and continued: ‘I said still here, eh, Rottcodd?’ He stared bitterly at the carving of the Emerald Horse. ‘You’re still here, eh?’

‘I’m invariably here,’ said Rottcodd, lowering his gleaming glasses and running his eyes all over Mr Flay’s visage. ‘Day in, day out, invariably. Very hot weather. Extremely stifling. Did you want anything?’

‘Nothing,’ said Flay and he turned towards Rottcodd with something menacing in his attitude. ‘I want nothing.’ He wiped the palms of his hands on his hips where the dark cloth shone like silk.

Rottcodd flicked ash from his shoes with the feather duster and tilted his bullet head. ‘Ah,’ he said in a non-committal way.

‘You say ‘‘ah’’,’ said Flay, turning his back on Rottcodd and beginning to walk down the coloured avenue, ‘but I tell you, it is more than ‘‘ah’’.’

‘Of course,’ said Rottcodd. ‘Much more, I dare say. But I fail to understand. I am a Curator.’ At this he drew his body up to full height and stood on the tips of his toes in the dust.

‘A what?’ said Flay, straggling above him for he had returned. ‘A curator?’

‘That is so,’ said Rottcodd, shaking his head. Flay made a hard noise in his throat. To Rottcodd it signified a complete lack of understanding and it annoyed him that the man should invade his province.

‘Curator,’ said Flay, after a ghastly silence, ‘I will tell you something. I know something. Eh?’

‘Well?’ said Rottcodd.

‘I’ll tell you,’ said Flay. ‘But first, what day is it? What month, and what year is it? Answer me.’

Rottcodd was puzzled at this question, but he was becoming a little intrigued. It was so obvious that the bony man had something on his mind, and he replied, ‘It is the eighth day of the eighth month, I am uncertain about the year. But why?’

In a voice almost inaudible Flay repeated ‘The eighth day of the eighth month’. His eyes were almost transparent as though in a country of ugly hills one were to find among the harsh rocks two sky-reflecting lakes. ‘Come here,’ he said, ‘come closer, Rottcodd, I will tell you. You don’t understand Gormenghast, what happens in Gormenghast – the things that happen – no, no. Below you, that’s where it all is, under this north wing. What are these things up here? These wooden things? No use now. Keep them, but no use now. Everything is moving. The castle is moving. Today, first time for years he’s alone, his Lordship. Not in my sight.’ Flay bit at his knuckle. ‘Bedchamber of Ladyship, that’s where he is. Lordship is beside himself: won’t have me, won’t let me in to see the New One. The New One. He’s come. He’s downstairs. I haven’t seen him.’ Flay bit at the corresponding knuckle on the other hand as though to balance the sensation. ‘No one’s been in. Of course not. I’ll be next. The birds are lined along the bedrail. Ravens, starlings, all the perishers, and the white rook. There’s a kestrel; claws through the pillow. My lady feeds them with crusts. Grain and crusts. Hardly seen her new-born. Heir to Gormenghast. Doesn’t look at him. But my lord keeps staring. Seen him through the grating. Needs me. Won’t let me in. Are you listening?’

Mr Rottcodd certainly was listening. In the first place he had never heard Mr Flay talk so much in his life before, and in the second place the news that a son had been born at long last to the ancient and historic house of Groan was, after all, an interesting tit-bit for a curator living alone on the upper storey of the desolate north wing. Here was something with which he could occupy his mind for some time to come. It was true, as Mr Flay pointed out, that he, Rottcodd, could not possibly feel the pulse of the castle as he lay in his hammock, for in point of fact Rottcodd had not even suspected that an heir was on its way. His meals came up in a miniature lift through darkness from the servants’ quarters many floors below and he slept in the ante-room at night and consequently he was completely cut off from the world and all its happenings. Flay had brought him real news. All the same he disliked being disturbed even when information of this magnitude was brought. What was passing through the bullet-shaped head was a question concerning Mr Flay’s entry. Why had Flay, who never in the normal course of events would have raised an eyebrow to acknowledge his presence – why had he now gone to the trouble of climbing to a part of the castle so foreign to him? And to force a conversation on a personality as unexpansive as his own. He ran his eyes over Mr Flay in his own peculiarly rapid way and surprised himself by saying suddenly, ‘To what may I attribute your presence, Mr Flay?’

‘What?’ said Flay, ‘what’s that?’ He looked down on Rottcodd and his eyes became glassy.

In truth Mr Flay had surprised himself. Why, indeed, he thought to himself, had he troubled to tell Rottcodd the news which meant so much to him? Why Rottcodd, of all people? He continued staring at the curator for some while, and the more he stood and pondered the clearer it became to him that the question he had been asked was, to say the very least, uncomfortably pertinent.

The little man in front of him had asked a simple and forthright question. It had been rather a poser. He took a couple of shambling steps towards Mr Rottcodd and then, forcing his hands into his trouser pockets, turned round very slowly on one heel.

‘Ah,’ he said at last, ‘I see what you mean, Rottcodd – I see what you mean.’

Rottcodd was longing to get back to his hammock and enjoy the luxury of being quite alone again, but his eye travelled even more speedily towards the visitor’s face when he heard the remark. Mr Flay had said that he saw what Rottcodd had meant. Had he really? Very interesting. What, by the way, had he meant? What precisely was it that Mr Flay had seen? He flicked an imaginary speck of dust from the gilded head of a dryad.

‘You are interested in the birth below?’ he inquired.

Flay stood for a while as though he had heard nothing, but after a few minutes it became obvious he was thunderstruck. ‘Interested!’ he cried in a deep, husky voice. ‘Interested! The child is a Groan. An authentic male Groan. Challenge to Change! No Change, Rottcodd. No Change!’

Illustration by Mervyn Peake

‘Ah,’ said Rottcodd. ‘I see your point, Mr Flay. But his lordship was not dying?’

‘No,’ said Mr Flay, ‘he was not dying, but teeth lengthen!’ and he strode to the wooden shutters with long, slow heron-like paces, and the dust rose behind him. When it had settled Rottcodd could see his angular parchment-coloured head leaning itself against the lintel of the window.

Mr Flay could not feel entirely satisfied with his answer to Rottcodd’s question covering the reason for his appearance in the Hall of the Bright Carvings. As he stood there by the window the question repeated itself to him again and again. Why Rottcodd? Why on earth Rottcodd? And yet he knew that directly he heard of the birth of the heir, when his dour nature had been stirred so violently that he had found himself itching to communicate his enthusiasm to another being – from that moment Rottcodd had leapt to his mind. Never of a communicative or enthusiastic nature he had found it difficult even under the emotional stress of the advent to inform Rottcodd of the facts. And, as has been remarked, he had surprised even himself not only for having unburdened himself at all, but for having done so in so short a time.

He turned, and saw that the Curator was standing wearily by the Piebald Shark, his small cropped round head moving to and fro like a bird’s, and his hands clasped before him with the feather duster between his fingers. He could see that Rottcodd was politely waiting for him to go. Altogether Mr Flay was in a peculiar state of mind. He was surprised at Mr Rottcodd for being so unimpressed at the news, and he was surprised at himself for having brought it. He took from his pocket a vast watch of silver and held it horizontally on the flat of his palm. ‘Must go,’ he said awkwardly. ‘Do you hear me, Rottcodd, I must go?’

‘Good of you to call,’ said Rottcodd. ‘Will you sign your name in the visitors’ book as you go out?’

‘No! Not a visitor.’ Flay brought his shoulders up to his ears. ‘Been with lordship thirty-seven years. Sign a book,’ he added contemptuously, and he spat into a far corner of the room.

‘As you wish,’ said Mr Rottcodd. ‘It was to the section of the visitors’ book devoted to the staff that I was referring.’

‘No!’ said Flay.

As he passed the curator on his way to the door he looked carefully at him as he came abreast, and the question rankled. Why? The castle was filled with the excitement of the nativity. All was alive with conjecture. There was no control. Rumour swept through the stronghold. Everywhere, in passage, archway, cloister, refectory, kitchen, dormitory, and hall it was the same. Why had he chosen the unenthusiastic Rottcodd? And then, in a flash he realized. He must have subconsciously known that the news would be new to no one else; that Rottcodd was virgin soil for his message, Rottcodd the curator who lived alone among the Bright Carvings was the only one on whom he could vent the tidings without jeopardizing his sullen dignity, and to whom although the knowledge would give rise to but little enthusiasm it would at least be new.

Having solved the problem in his mind and having realized in a dullish way that the conclusion was particularly mundane and uninspired, and that there was no question of his soul calling along the corridors and up the stairs to the soul of Rottcodd, Mr Flay in a thin straddling manner moved along the passages of the north wing and down the curve of stone steps that led to the stone quadrangle, feeling the while a curious disillusion, a sense of having suffered a loss of dignity, and a feeling of being thankful that his visit to Rottcodd had been unobserved and that Rottcodd himself was well hidden from the world in the Hall of the Bright Carvings.