As a student way back in 1979, I vowed to read each and every book in the Glades Junior High School library, under the watchful tutelage of our school librarian, Miss Franklin—a woman with a sparkling smile and calm intelligence shining from her brown eyes. She made gentle suggestions and supervised my journey through her bookshelves.

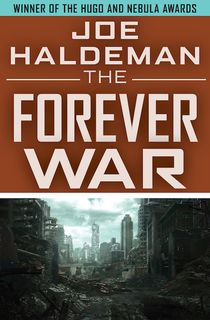

Being more than a bit OCD, I worked my way down each shelf alphabetically—reading whatever books I found there. When I hit the shelf with authors whose last names began with “H,” I met Joe Haldeman and his brilliant novel, The Forever War.

The story is about futuristic soldiers—a man named Mandella, specifically—who slowly lose focus on why, exactly, they are fighting. Due to the nature of time dilation during relativistic space travel, what takes a year or two in the field translates to decades back home. The people who send them into battle are dead and gone when they return back home.

The more fighting they see, the more tenuous becomes the rationale for fighting in the first place. Eventually, due to nothing more than blind luck and good fortune, Mandella becomes the oldest original soldier from the war that began in 1997. It’s now centuries later, and the only thing that ties him to his own time is his love, Marygay, who fights alongside him and eventually drifts away on her own mission.

Being 11 years old at the time I first read this, I thought that violence and war were noble pursuits, oblivious to my own eventual mortality. I delighted in joining Mandella while he fought the evil Taurans, with their bubble machines and their neckless bodies, giant heads erupting directly from their chests. The psychological impact of combat on the soldiers didn’t register with me at all; I was anxious to see to the viscera, the bloody stumps, and the detonations of war.

Now I’m 50 and happened to re-read the same book last year—almost 40 years after reading it the first time.

I’m a father of three now, and having children changed my perceptions of life and death—re-allocating my priorities drastically. When you’re 11 years old, death is always meant for the other guy, never for you.

But when you’re 50, death has become a frequent visitor, and fathering children has made that specter a greatly feared foe.

Re-reading The Forever War brought me quite a bit of nostalgia during the scenes I remembered reading the first time around, but with a renewed appreciation for the brilliant novel Haldeman has crafted. With the sharp eye of a combat veteran, he knits a world from the skein of a survivor, showing how the very concept of what it means to be human might shift and flow as the centuries progress.

Haldeman paints an insightful and biting landscape of what war might mean when it is dissected and examined piecemeal, and I found it loaded with wisdom, clarity, and love.

His work speaks to me, as a father, and perhaps most potently after Mandella sees his first dead Tauran, the desired objective of all their training. He says, “I felt my gorge rising and knew that all the lurid training tapes, all the horrible deaths in training accidents, hadn’t prepared me for this sudden reality … that I had a magic wand that I could point at a life and make it a smoking piece of half-raw meat; I wasn’t a soldier nor ever wanted to be one.”

As a pre-teen, I thrilled at the glory of battle, and I delighted in the gory scenes, feeling the thrum of the futuristic weapons in my own hands, seeing the alien blood splatter across the page as I joyfully followed Mandella along.

As a father, I’m sympathetic to Mandella’s increasing sense of displacement, recognizing the horror of burning down enemy combatants who, from their point of view, are being murdered by rapacious invaders. Specifically, I see the carnage of a taut battle scene as wasteful; it is no longer a source of visceral joy. The slaughtered Taurans, who I now recognize through the lens of a parent, are somebody else’s sons and daughters, no matter how alien they may be to Mandella’s xenophobic eyes.

Haldeman’s deft touch and demonstration of the futility of war in solving political disputes resonates strongly in my adult self, while having been completely oblivious to me as a child.

If you are a fan of Haldeman’s The Forever War, you might also like the following:

- Old Man’s War, by John Scalzi: The author posits that a military career can take place after you have already lived a full, combat-free life. John Perry goes from his dead wife’s graveside straight to the recruiting office, where his old, worn-out body is swapped for a new one—young and in great physical shape, ready for combat. Imagine a lifetime of wisdom and experience residing in the fit frame of a twenty-year-old. The only rule? You can’t ever come home again.

- Sleeper Protocol, by Kevin Ikenberry: The book follows a combat soldier who gave his life to protect his fellow soldiers, only to awaken 300 years later in a new body with no memories. His instructions are to go on walkabout and find himself, unaware that he’ll be killed if he doesn’t rediscover his identity and past quickly enough. What he’s further unaware of is that he may very well be killed anyway because his 300-year-old memories are still dangerous.

- Speaker For the Dead, by Orson Scott Card: The second book in the Ender’s Game series follows Ender’s psychological journey after his unwitting contribution to the genocide of an entire alien race becomes apparent. He is appalled by what he did as a commander in war, albeit after the fact.

- Terms of Enlistment, by Marko Kloos: The book follows Andrew Grayson’s decision to escape the tenement slums of his youth by enlisting in the service. Who he ends up fighting, however, comes as a complete surprise—causing him to question his entire decision about joining up.

This post is sponsored by Open Road Media. Thank you for supporting our partners, who make it possible for The Portalist to celebrate the sci-fi and fantasy stories you love.