In this Marvel comic novelization that reads like noir fiction, New York City private investigator Jessica Jones is as unstoppable as ever—at least, on the outside. She still has her super strength and endurance, but between a string of gruesome cases and her own personal trauma, her mental health is cracking under the weight of a city that constantly needs to be saved.

Jessica decides to give therapy a try, even promising her therapist to take on a couple of lighter cases while her psyche heals. But when a teenage boy goes missing, she doesn't have the heart to refuse his desperate family. When she discovers his body, dead of an apparent drug overdose, she starts to regret her decision.

But, Jessica knows this case isn't as closed as it seems. Against the advice of her friends and therapist, she investigates further, and the secrets she discovers may just point to her darkest mystery yet.

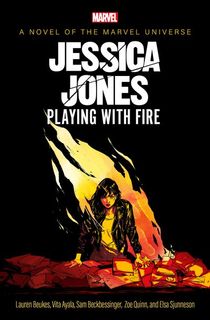

Jessica Jones: Playing With Fire is a collaborative novel by Lauren Beukes, Vita Ayala, Sam Beckbessinger, Zoe Quinn, and Elsa Sjunneson, based on the Marvel comic series. To find out more about Jessica's battle for the city's safety and her own psychological wellbeing, read chapter one below, then download the book for the full story!

The ice cream truck screams through the docks of New Jersey, while Jessica Jones clings to the fiberglass mascot of Captain Cone perched on top. As the name suggests, he’s a nautically themed soft-serve-man hybrid, grinning down at her with cold dead eyes as she digs her fingers into his waffle cone torso.

The tinkly ice cream jingle is going off right next to her head, and Jessica punches the speakers to make it stop. The metal crumples under her fist and the music distorts but doesn’t die, becoming a sicklier version of itself, but just as loud. And now one of the soft-serve gangsters is leaning out the passenger window to try grabbing her, ridiculous in his sailor hat. And dammit, she did not sign up for this. She has therapy in an hour.

The gangster pulls on her leather jacket and she rolls off the roof, still hanging on by one hand. She thuds into the back of the van, denting the doors. Better in than out. She swings out and kicks, hard, against the back so the metal buckles like tinfoil.

Inside: yup, as she suspected, a dead body in the open freezer among the ice pops, wearing the uniform of the rival company. Mr. Icey got iced, she thinks, propelling herself into the van. If she can make it to the front before the guy in the sailor hat figures she’s inside, she can punch out the driver, take the wheel.

But the driver catches a glimpse of her in the rear-view mirror and yelps; he veers left. He’s underestimated his speed. Dude, ice cream vans aren’t made for drifting. The truck mounts the sidewalk with a tectonic jolt and flips. And flips again. She drops low, tries to maintain her center of gravity, but gravity’s a bastard like that. Physics, too, even when it’s gone into adrenaline-induced slo-mo.

A scream from the guy who was leaning out the window as he hits the tarmac. The van tumbles over and over. There’s a scrunch of fiberglass cracking like a crab shell. The dead guy lifts off the ice like the ghost of ice creams past, with the ice pops floating up around him, before everyone and everything comes crashing down again. The last tumble.

The van grinds across the road on its side, trailing sparks in its wake. Jessica wedges herself against the soft-serve machine, waiting for friction to take its toll, slower and slower, until it finally comes to rest against a container.

The driver’s face is a bloody ruin where it met the windshield, which is why you should always wear your seatbelt, kids. But he’s still breathing.

The front door is so crumpled, she basically has to rip it off its hinges to clamber out. A man in a yellow hard hat behind the wheel of a tractor is gaping at the scene. She gives him a wave, like, Yeah, everything’s okay, reaching into her jacket for her phone to call her lawyer. Matt Murdock needs to get down here to clean up the mess he got her into.

It’ll be a cinch, he said, it’s an ice cream turf war, he said, and sure they’re getting a little heavy, but nothing you can’t handle.

She notices, irritated, that her screen has cracked. Also, in the black mirror reflection, goon number one is limping up behind her.

“Oh, hell no,” Jessica says. She turns and punches him out.

Her therapist would not approve, Jessica thinks, as she casually prowls the office of Dr. Melody Hollman. Outside the window, the fall wind stirs, and branches scratch against the glass. Jessica knows she shouldn’t be snooping. The good doctor could come in at any moment. But it’s hard to fight your very nature.

The desk is buried under a chaos of books and papers, and there’s nothing especially surprising here. A photograph of a four-year-old boy, freckled, with curls escaping his hat. There are academic journals, admin-ny paperwork, a heating bill, and a battered book, In the Dream House by Carmen Maria Machado—maybe a little too Jungian, given what she knows about Mel. Which is not that much, due to the fact that they spend most of their time together talking about Jessica.

An amateur might mistake that creak for the branches of the maple scraping against the window again, but Jessica knows (intimately) the sound of a door handle being opened, and she is already back in her seat on the overstuffed couch by the time Melody, psychologist-at-large (and she means at large, because she’s seven months into her pregnancy), enters the room.

“What happened to your face?” her psych asks, frowning at Jessica over her crimson cat-eye glasses.

Jessica reaches up and feels a patch of dried blood on her temple. Must’ve been the corner of the soft-serve machine plowing into her face when the Captain Cone van took its tumble.

“Oh nothing,” she says. She clicks her neck, rolls her left shoulder, which is tender from the altercation. Her body will recover, but her jacket sleeve got ripped, her phone screen is spiderwebbed, and she’s going to have that tinkling jingle in her head for months.

“I very much doubt it was nothing.” Her psych sighs, glancing over at her desk. “Wait, were you snooping?”

“Yes,” Jessica admits, feeling only a tiny bit guilty. “Sorry.”

“Please don’t do that,” Mel says. She hands Jessica a tissue and lowers herself into the cracked leather armchair facing the couch. “I don’t want to fire you as a patient.” She takes her notebook from her handbag and shoves one of the cushions behind her back. It’s covered in red sequins, the kind that you might be able to swipe up to reveal Nicolas Cage’s face, if Mel was into irreverent decor. Jessica thinks she might be, which is part of the reason she’s kept coming back week after week.

“Wouldn’t be the first time,” Jessica says as she cleans the blood off her face. Mel is her fifth attempt at “getting help,” although usually she quits before anyone has the chance to fire her.

“Where do you think the urge to sabotage your therapy comes from?” Mel asks with quiet, bright-eyed interest. Also one of the things that keeps Jessica coming back.

“Don’t we all know the chorus to this one already?”

Mel suppresses a smile. “You’re evading the question,” she says, not having it.

“Really. What do you think?”

Unlike her previous therapists, Mel has experience in dealing with people like Jessica and their uniquely traumatic traumas. Like ice cream wars, for example. The ice-cream jingle returns with a vengeance then, and she glimpses a vision of the dead man floating among the ice pops, his head busted, and blood on the ice.

“C-PTSD makes me mean,” she says flatly. She catches Mel’s raised eyebrow and corrects herself. “Makes me behave mean. Sometimes.”

“That’s not a fair—”

“Okay,” Jessica interrupts. “Yeah. It makes me feel like I can’t trust people, that I always see the worst in any situation.” Which is hard not to do when the world is full of evil bastards and people willing to murder each other over waffle cone profits.

“And?”

“I need to try harder.”

“You need to be kinder to yourself. Maybe take on a case that isn’t going to wreck you emotionally for months afterwards.”

“I heal up quick.” Jessica shrugs. “Super-powers.”

“I said emotionally. Psychologically. You’re already dealing with a lot. Your latest case?”

“It’ll keep me for a few weeks,” she admits.

“So, and I know this is a preposterous suggestion, maybe take a vacation.”

Jessica laughs. “Not going to happen.”

“Then find a case that’s not going to eat you alive. Something straightforward and uncomplicated that you can fix easily. That you’re not going to take personally.”

“It’s all personal, Mel.”

“Think about what you need, that’s all I’m suggesting.”

Twenty subway stops, two line changes, and a half-mile of walking (which she could have flown if she didn’t suck so much at landing) later, Jessica is back at her own office in Hell’s Kitchen, which wishes it had trees growing outside that could get tall enough to scratch at the windows.

The glass of the door is cracked where someone tried to kick it in two months ago. And she barely has furniture, let alone red-sequined novelty cushions. Maybe she could shift gears in her career, become a well-paid psych instead of a PI. It’s kind of a deep-dive internal investigation, isn’t it? And how hard can it be to tell people to be nicer to themselves? She could do that. It would involve less punching people in the face, definitely.

Her part-time assistant, Malcolm, nervy and gawky even for a millennial, opens the door before she can reach for the handle. She’d forgotten it was one of the days he liked to drift in and cluck over her paperwork.

“You have a client,” he hisses, as if this is a revelation. “He’s been waiting for an hour. Where have you been?”

“Therapy.” Jessica shrugs out of her scraped-up leather jacket.

“Oh, right.” Malcolm beams like the proud dad she doesn’t have, which is super annoying and downright patronizing. “Every Wednesday. I forgot. But I’m really glad you’re still going.”

“Hang this up. Coffee, please. Black.”

“Like midnight on the subway in a blackout, I know, I know. You got it.”

Jessica glances into the waiting room, where there is not, in fact, a client waiting, though she can make out a man’s hunched profile seated in front of her desk.

“You let him in my office?” She’s incredulous.

“The couch is broken,” Malcolm says, examining the rip on her jacket. “You should probably fix this.”

“Add it to the list.”

Take a vacation. Ha.

“Hey, sorry to keep you waiting,” she says, crossing the room to turn off the police radio, which Malcolm should have done before letting the client in. Some people listen to music at work; she tunes in to Channel Crime.

The man stands up to greet her. Late fifties, tall despite his hunched shoulders. He has the rumpled look of someone who has been up all night, his face slack and puffy, cheeks red with broken veins.

“I’m Jessica Jones.” She reaches to shake his hand.

“I’m Colin. Colin Greene from Bloomington, Indiana.”

“And what can I help you with, Colin Greene from Bloomington?”

“It’s my son, Jamie. He’s missing, and the police won’t help me. They say I have to wait three days. Three days!”

Jessica reaches to open her bottom left desk drawer, the sticky one that grinds along the dented track. There’s still a half-quart of bourbon in there, the amber liquid sluicing from side to side. Her fingers glide over the bottle, feeling for her notebook instead.

See, Mel, she thinks, being kinder right here. No business-hours drinking. She’s not even going to offer Mr. Greene a slug, though the man could clearly use it. She flicks open the pad and clicks her cheap ballpoint, giving him time to compose himself.

“How old is he? Are we talking about a little kid or an adult? When did you realize he was missing?”

“He’s twenty, all grown up, and it was yesterday, when I got to the airport and he wasn’t waiting for me like he said he would be.”

He sees her skeptical look. Airport pick-ups go wrong all the time.

“You’ve got to understand, it’s a big deal. It’s been two years. We’re both really trying. He was excited to see me, show me around, introduce me to his friends. We were going to catch a Broadway show, have dinner with his commune friends. But he didn’t show, and I don’t have his address, so I went looking for him at that club he works at. The Hellhole. No, that’s not it. The Hellfire. But they wouldn’t let me in, wouldn’t talk to me, because I was wearing the wrong shoes!” He thumps the desk so hard it rattles the drawers, and clearly instantly regrets it.

Jessica waves off his apology. “It’s seen worse. Hazard of the job. I want to hear more about this club, and this commune, but let’s back up a little, huh? Slow down.”

Colin Greene sags. “Jamie wouldn’t do this. We’ve had our differences, but he wouldn’t disappear like this. Not without saying anything. He was excited to see me. We’re supposed to be making up for all the lost time.” His voice hitches and he covers his eyes with one huge hand, knuckles like bird skulls. “Excuse me.”

Jessica gives him a moment. Lost time; two years. That’s a big falling-out. The way the man said “Broadway,” with a little bit of bafflement. She’s getting more conservative vibes, which can be hard to deal with if you’re an arty weirdo kid.

Jamie could have run away to Chicago, only one state over from Indiana, but he came all the way to New York. He wanted to get as far away as possible.

There’s always the possibility his dad hit him, she thinks, looking at those huge knuckles. It would also explain the no-show. She’s seen a lot of abusers, though, and her domestic violence sense isn’t tingling. For now. She’ll give Mr. Greene the benefit of the doubt until he gives her cause to think otherwise. It’s early days.

“Would you like a glass of water? An iced tea?”

He shakes his head, a small, tight no. Barely holding it together. “He’s my boy. My only boy. Just him and me in the world. I shouldn’t have thrown him out.” He trails off and his whole body racks in a sob. Grief, worry, up all night. There’s a reason sleep deprivation is a method of torture. But Jessica was on the money about the estrangement. No mom in the picture, either.

“Malcolm,” she calls out. “Can we get a sweet iced tea in here?”

Her assistant pokes his head in, frowning. “Um. We don’t have a refrigerator.”

“From the bodega. Cash in my jacket pocket.”

“You want an ice cream, too?” Malcolm quips and she briefly considers adding him to the list of soft-serve-related casualties. What’s one more dead body?

“Water, just water, please,” Colin says. Malcolm ducks off to get it, smirking. She could still kill him, she reckons. Pity he’s useful.

“Tell me about Jamie,” she says, as Colin gulps down water from a mug that might or might not have been washed before being filled.

“Yes. Right. Thank you.” He smooths his hands on his jeans like he’s ironing them flat, front and back. “He’s twenty. I said that. Almost twenty-one. I’ve got a photo—hang on.” He swipes through his phone and reaches over to show her the image: a goofy, grinning kid—young adult, really—but Jessica can’t help but think of everyone under twenty-five as kids. He’s got unruly-on-purpose hair, a little bit nineties boy band. He’s wearing an Indiana University sweater, and sprawling on a dorm bed, mugging for the camera with a double thumbs-up.

“That’s from two years ago,” Colin apologizes. “I don’t have a more recent one.”

“Those differences you mentioned?”

“He dropped out of college. He was doing engineering at UI, like I did. He’s got the mind for it, but he wants to be an artist. An artist! There’s no money in art.”

“You said you threw him out? Because he gave up on college?”

“He was … uh.” Colin flushes. Uh-oh. Her small-minded-bullcrap detector is flashing. He manages to look her full in the face. “A freak. Like you. That’s why I came to you, because I knew you’d understand.”

“How thoughtful.” Jessica smiles. It’s a complicated smile, part screw-you-I-see-why-he-left-home and part I-guess-bigots-need-help-too.

Colin blunders on. “He’s got powers. No iron-fisting through solid walls, or flying, or super speed. More like party tricks, you know? We thought he was a pyromaniac, always setting things on fire, but turns out that’s his thing.”

“His freakishness?” She’s not quite ready to let that one go.

“You know what I mean.” He has the decency to blush. “He hid it all his life. His mom never knew, rest her soul. She died—cancer—the same year Jamie burned down the art room at his high school. They wanted to expel him, send him to a juvenile detention center, but he didn’t do it on purpose! He was emotional; his mom had passed. He was angry. He couldn’t control his powers.”

“Sounds more serious than a ‘party trick.’”

Colin gives a sad humph of a laugh. “It didn’t take much. The fire department said there’s a lot of flammable items in an art classroom: paper and paints, the chemicals they use to clean the brushes. I wanted to send him for repression therapy—have you heard about it?”

“Oh boy, have I.” Pure dangerous, this smile, this time. Psychological torture camps pretending to help you get control of your powers, press them down deep. But everything that gets pushed down comes back up for air, she’s found. Problems have their own buoyancy.

“I know it’s controversial, but I wanted him to have a normal life. That’s important, isn’t it? To be able to fit in?”

“If you say so,” she says in her most neutral tone. Meaning: hard disagree.

“He said he wouldn’t go. Said he’d rather kill himself. So I threw him out. It was supposed to be a time for him to cool off. Tough love. I thought he’d come ’round. But he didn’t. He came to New York. All this way. I was so angry. I said … some things. I’ve spent the last two years regretting them.”

“Did it ever escalate beyond words?”

“You mean did I hit him?” He goes white, with horror rather than guilt, she estimates. “No. God, no. Do I regret it? I do. All of it. I was trying to do the best by him, and I screwed up. I don’t blame him for running away.” He shakes his head, a kind of doggy remorse that’s endearing. “You ever been estranged from your family, Ms. Jones?”

“In a manner of speaking.” Does the death of everyone you love count?

“Then you know. It’s a crevasse inside you and you think you can ignore it, but it gets bigger and bigger and it swallows the ground underneath you until that’s all you can think about: what you’ve lost. I reached out. Started slow, some texting, phone calls once a month. I tried to make up for it, I did. I told him how sorry I was. He told me about his new life here. He invited me to fly out to see him.”

Jessica nods, schooling her face into something attentive and neutral. She asks, as gently as possible, “What makes you sure he didn’t change his mind?”

“I know my son, Ms. Jones. He doesn’t flake out. He wouldn’t do this. I came all this way. We had plans. We had Broadway tickets. Here. Listen!” He fumbles for his phone. Plays her a voice note.

A young man’s playful tenor comes out of the speaker: “Yo, Pops, you better bring Mrs. Barkdale’s cookies. If you’ve already left for the airport without the cookies, you should turn back and go get them cookies. I’m not even kidding, old dude. JK. I am kidding. Can’t wait to see you …” His voice trails off and then, a beat later, he rasps in a scary monster voice: “Bring cooooookies.” The voice note dissolves into high-pitched laughter, easy, childlike, before it cuts off.

Jessica has to agree it doesn’t sound like someone planning to blow off his estranged father at the airport. And it is exactly the kind of softball case Mel wants her to do more of. And Colin Greene is digging in his wallet, proffering a wad of bills.

“Please. I can pay. I think he’s in trouble, Ms. Jones. This club he works for is sketchy. Who knows what goes on there? I don’t have the address for the commune, or anyone to contact there. They’re all flares, too. I know what young people are like, even without powers. They could be into …”

“Freakish things?” she deadpans. But she does wonder what Colin fears. That Jamie has been recruited into a school for baby super-villains?

“… Drugs,” he finishes. “He really can’t mess around with drugs.”

“Mr. Greene, I will do everything I can to find him. But if—”

He cuts her off. “If it turns out he’s changed his mind about seeing me, I guess I can live with that. But I need to know where he is. I need to know he’s okay.”

She flips her notebook shut. “I’ll start with the Hellfire, then, if that’s what we have to go on.”

“Thank you. Really.” He pumps her hand, a little teary. “Thank you.”

“Thank me when I’ve found him, Mr. Greene.” She ushers him out.

Malcolm raises his eyebrows at her.

“What?”

“I’m impressed with your restraint, is all. After the first ‘freak’ I was expecting you to throw him out the window. Therapy is working for you!”

Jessica shrugs. “Eh. It’s money for nothing. I’ll have it wrapped up by this evening.” Kid couldn’t deal with the awkward reunion, and who could blame him? But she’ll find him, assuage Mr. Greene’s concerns, maybe even facilitate a meet-up down the line. Happy families. Kumbaya.

An easy, straightforward case. No emotional involvement. Just what her therapist ordered.

“If you say so, boss.” Malcolm goes back to scanning her case files.

New York in fall is just delightful, Jessica thinks. Above-ground. It’s all crisp air and blue skies and trees in red and gold. Below-ground, it’s a stinking, humid mess. The subway at 49th Street is sweltering, people standing sweating in their scarves and woolen jackets, trying to decide whether to take them off before the train arrives, knowing they’ll have to put them on the moment they get in. This city has ways of making you uncomfortable.

She’s taking Occam’s shortcut: straight to Jamie’s place of work, this Hellfire Club that apparently employs kids with powers to perform stunts for the clientele. She had a look at the website before heading down, but it’s one of those places in Bushwick that is too damn hip to advertise.

The URL goes to a black page with a logo and opening hours. Eight p.m. till late. Guess you have to be cool enough to know the address already. Or have mad PI skills and be able to pick it up from the DNS registration information. Natch. Corroborated by hashtags on Instagram attached to photographs of the beautiful people, cross-referenced against location tags. The images are exterior only, which suggests the club has a no-photos policy, and isn’t that interesting?

It’s a start. She’d have liked to find Jamie at home, wherever that is, but all Colin gave her to go on was “arty-farty commune,” which could describe any number of places ranging from an illegal squat in a condemned building in Queens to one of those awful tech-bro co-living dorms where everyone gets a single-person pod for $1500 a month.

She’s already tried to call Jamie, but his number goes straight to voicemail, so she snoops through his social media while the N train rattles her downtown for her transfer. There’s not a lot to go on. Unusual for his generation, she thinks, as she swipes through the little he’s made public. Maybe he’s preoccupied with protecting his privacy and trying to stop the world burning. Or maybe he’s been stalked. Maybe even by his dad. Could be the happy reunion Colin was painting for her was not what his son wanted at all.

Finally, she finds a photograph on the low-fi arts and culture site his dad mentioned. She’s ninety per cent sure it’s him. He’s leaner, cut his hair into a cool undercut, with a spangle of plastic stars dangling from one ear, ironic tie-dye vest. He’s wearing a smile that’s all mischief, standing in front of a mural of abstract spikes and curves in neon colors with dark smears cut through. The caption reads J*pup.

She transfers to the L train. Once she emerges from the subway, she walks through Bushwick’s industrial clutter of warehouses and storage facilities and a shuttered used-car dealership. There are some signs of life as she gets closer—apartment blocks, a bodega on the corner, a pizza-slice place, a Chinese medicine practice—but it’s not exactly a happening part of town. Maybe the clientele prefers it that way. Pigeons trill from ledges above.

When she arrives, The Hellfire is closed. Which is not a surprise at four in the afternoon. It’s a converted tannery, blank, private, the kind of place where anything could be happening inside, and you wouldn’t know about it.

The façade is original brick and faceless, apart from a dark glass box that runs the length of the second floor. It’s half-open, with sliding floor-to-ceiling windows that fold open and stack up against each other. From down here, she can make out heavy furniture that looks very gentleman’s club, and the sheen of a long gold bar that undulates against the far wall. There’s a low thrum from upstairs, almost subsonic.

A meaty bouncer, neck pink and thick as a Christmas ham, with a beanie pulled down so low his eyebrows have disappeared, is standing outside the door. Good watchdog. He is shaking his head at her before she even reaches him.

“Not till eight,” he grunts.

“Is the manager here? Someone I can talk to?”

“Not till eight,” he repeats.

“I heard the club’s hiring people with powers. What do they call them, flares?”

“Huh. You looking?”

“I might be.”

“You got some tricks you want to show me?” He leers.

Jessica casts around for something to demonstrate, settles on a half-brick, and picks it up.

“You going to do some juggling?”

“Don’t have the finesse.” She crushes it to powder in her fist and dusts off her hands. “You really have to see it in context of the routine, but what do you think? Do I have what it takes?”

He grunts again, but with less bravado. “Not up to me. Come back at six. Mr. Shaw gets in then, along with the rest of the staff.”

“You’re really not going to let me wait?”

“Against club policy. Come back later.”

She makes as if to head off, but circles round the back instead. The black box doesn’t extend all the way through the building. The rear is all-brick, with a row of tiny windows running along the very top, all standing open, gaping like hungry mouths. The delivery receiving area is also open.

How convenient, she thinks, strolling inside.