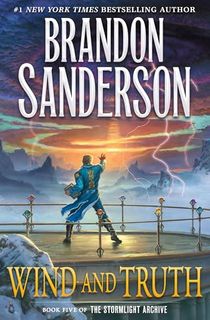

It’s been three years since Brandon Sanderson released The Rhythm of War, a massive tome in his epic Stormlight Archive, which means that readers are due for a new book any day now. Sanderson has a reputation for churning out novels at a remarkable and predictable rate, and sure enough, Wind and Truth is set to hit bookshelves within the week (December 6, to be exact). As the capstone of a five-book journey, Wind and Truth has a lot to live up to, and it clocks in at a whopping 1,344 pages. That alone would be a massive project for any author, but Sanderson has published many other books in the interim, including The Lost Metal (a Mistborn title) and Tress of the Emerald Sea.

It’s really hard to write a single draft of a book. Most give up somewhere along the way, and even the best speculative authors in the world can struggle to meet deadlines.

I know firsthand the sort of challenges that an author faces—the self-doubt, the rewrites, the negative feedback—to finish a book and actually feel proud of the final product. Given such challenges, it’s worth celebrating Sanderson’s efficiency … and studying it.

As with all writing advice, it’s unlikely that Sanderson’s process will be a perfect match for your own lifestyle and writing goals. But, if you’re able to incorporate one or two of his habits into your own routine, it might just help you finish that tricky draft in a timely manner.

So, how does Sanderson write these books so darn fast? Let’s start with the most obvious and least helpful thing.

Brandon Sanderson is a full-time, bestselling author.

If we’re talking about how to adopt Sanderson’s writing pace, we have to mention that he has some advantages you probably don’t. As a full-time author, Sanderson is able to write for eight hours a day. As he writes in his blog, he wakes up around noon and writes from 1:00 p.m. to 5:00 p.m. every day, then does a second four-hour shift from 10:00 p.m. to 2:00 a.m. every day.

If you work a normal 9-to-5 like me, it’s probably not practical to write until 2 in the morning every day. You can’t just wake up at noon. You might only have 30 minutes a day, or 30 minutes a week, where you’re free to write.

Sanderson also has a trusted team of editors, agents, beta readers, and a writing group that can help streamline some aspects of his work. For example, if you’ve read The Stormlight Archive, you’re likely familiar with spren. These fairy-like creatures are drawn to intense emotions, creating a sort of visual effect. When a character does something amazing, glory spren arrive in white and gold, forming something like an aura.

Sanderson doesn’t write the spren into his first draft. He simply writes the novel and asks his editor to note when it would be best to add that visual effect, almost like adding CGI to a movie.

These are just a couple of ways in which Sanderson might have a natural advantage over you and your busy schedule. However, Sanderson is outpacing other bestselling authors who enjoy similar success and support, so it’s clear he’s doing something right.

Let’s dig into some of the strategies, priorities, and techniques you actually can use.

Sanderson writes with intention.

Listen to Sanderson talk about his writing process, and it’s clear that he’s spent a lot of time thinking about what works best for him. He writes in two separate four-hour shifts because he tends to lose steam after four hours, but he needs enough time to get into a rhythm. He knows that the first hour and the last hour will typically be less efficient than the middle two hours, but that’s the price of doing business. He knows that over the course of eight hours, he will write about 2,000-2,500 words.

Whether you measure your work in time, pages, or words, it’s good to have goals as a writer—goals that feel attainable and not overwhelming. Writing a book is a marathon, not a sprint, and you need to set your own pace. For Sanderson, that might be 2,000 words per day, but he recommends that new authors try for that many per week. That way, you can write a full novel (typically 100,000 words) in one year.

And while you might not want to write from 10 p.m. to 2 a.m. every day, there’s a method to Sanderson’s madness. As a father, Sanderson understands that writing in the dead of night when his children are asleep is one of his best chances for uninterrupted focus.

Avoiding distractions can be a massive challenge for writers, especially in a digital world. When I get stuck in a scene, it’s so easy to turn away from the frustration and go scroll through social media. Next thing I know, an hour has passed and I haven’t written anything, which only amplifies the frustration. That’s why I have transitioned to writing my books by hand in a tablet or an old-fashioned notebook—it’s easier to focus that way.

Neil Gaiman has a similar rule. In a podcast with Tim Ferriss, Gaiman said that when he enters his writing space, he allows himself just two options: to write or to do nothing at all. “I’m not allowed to do a crossword, not allowed to read a book, not allowed to phone a friend … and what I love about that is I’m giving myself the permission to write or not write, but writing is actually more interesting than doing nothing after a while.”

I love this idea, and I think it’s also important to note that Gaiman is intentional about dedicating a physical space for writing. It’s often most convenient to do your writing at home, but home is also where the most distractions lie. If you have enough space, try reserving a distinct room for writing and leave your distractions (and your smartphone) outside. Or, don’t be afraid to be a cliche: Coffee shops are great for limiting your screen time and getting a relaxing environment for writing.

Figure out a place that helps optimize your work and decide how much time you can allot to your writing. Figure out whether you like to write in the morning or at night. But don’t make your writing compete with Instagram Reels or video games or whatever your vice might be. When you write, try to write with intention.

Sanderson doesn’t waste time in the weeds.

You might not realize it, but there’s one more, subtler form of distraction that can happen when writing a book: You can distract yourself with the book itself. There are a lot of different ways that this can happen, and all of them are well-intentioned. However, they don’t actually contribute to your goal of writing a book. Let’s go over a couple of these in-book distractions.

Languishing over language choices in a first draft.

There’s a degree of arrogance in choosing to write a book. We all want to think that we’re crafting a masterpiece—something that has never been done before, despite the millions of books already published. We want to prove that we have a unique outlook and a distinct voice.

But we don’t have to prove ourselves on every line and word choice—in fact, trying to do so may just end up making your prose seem strained. Here’s a simple example: When Sanderson has a character say something in his book, he almost always uses the simplest dialogue tag. “Kaladin said” or “Dalinar asked.” We don’t always need characters to be muttering or shrieking or whispering—that’s not how people communicate. Running to the thesaurus for every perfect word is impractical and will put off the reader.

There’s a classic Ernest Hemingway quote about this that I appreciate. After William Faulkner accused him of using overly simple prose, Hemingway said, “Poor Faulkner. Does he really think big emotions come from big words? He thinks I don’t know the ten-dollar words. I know them all right. But there are older and simpler and better words, and those are the ones I use.”

Sanderson describes his own style as “window-pane prose” as opposed to “stained glass prose.” Most of the time he wants the language itself to be the means by which the story is delivered—that the story itself should take precedence over the medium.

Of course, that’s not to say you should entirely forget your medium. You can see that Sanderson picks his spots on when to use his ten-dollar words—often with Hoid (otherwise known as Wit). But, being a perfectionist is going to slow you down, and it’s often a waste of time to even try on a first draft. When you start revising, you might end up cutting a chapter you spent two months on. Even worse, you might choose to keep a chapter that doesn’t fit just because of how hard you worked on it.

Get the big stuff right—plot, character arcs, setting—before you get down to sentence-level edits.

World-builder’s disease.

This piece of advice might sound strange coming from the creator of the Cosmere, but listen to Sanderson’s lectures and you’ll hear something important: An author’s job is to write a book and tell a story, not to build a world. While Fire and Blood is an amazing achievement by George R.R. Martin, it can’t replace The Winds of Winter. Readers want Patrick Rothfuss to write The Doors of Stone, not expand his Bast short story into a novella.

Of course, authors like Martin and Rothfuss have nailed their world-building and elevated the standard for other writers, so I understand the pressure to nail your magic system, your setting, and your history. But Sanderson uses a metaphor I love in regard to his own approach to world-building, which is the false iceberg.

An iceberg shows a little of its mass above the surface of the water, but its depths are unseen. In Sanderson’s metaphor, the unseen depths of the false iceberg are an illusion. They don’t exist.

You don’t need to create an entire, 500-page encyclopedia about the history of your world. You just need to do enough to make the reader confident that you know what you’re doing.

How do you do that? Sanderson recommends drilling deep on one very specific aspect of your world-building. If your book is about the clash between cultures, maybe you decide to really build out the world religions. You can see this exact clash in The Stormlight Archive, as well as how Sanderson uses it to his advantage. We see how women wear gloves on their “safe hands” due to religious taboo, while men do not read. We see how these small changes can change the entire course of society, as men depend on women for communication, while women can keep secrets on the page. We see the scandal that occurs when one man learns to read, etc.

These choices make the world feel lived-in. They also shape the characters and progress the plot. They’re useful and intentional decisions, not thought exercises.

Make sure that your world-building is also story-building.

Wind and Truth: Book Five of the Stormlight Archive (The Stormlight Archive, 5)

The first arc of Brandon Sanderson's The Stormlight Archive comes to a close with Wind and Truth. Dalinar Kholin has challenged the god Odium to a contest of champions, but who will each side choose … and who will come out on top?

Meanwhile, desperate fighting continues across the world, while Shallan and others work to unravel an ancient mystery. Can they solve the secret of Ba-Ado-Mishram before time runs out? The entirety of the Cosmere hangs in the balance.

Sanderson knows how to use feedback.

If I could give first-time authors one piece of advice, it’s this: People are not going to like everything about your book. Sanderson wrote several books before Elantris got published, and as a Sanderson fan, I have to confess that Elantris is … not my favorite.

Elantris has more than 23,000 reviews on Amazon, and it averages a 4.6 rating. It’s doing just fine without my approval. But if you’re like me, you don’t have thousands of devoted fans to give you feedback (and even for Sanderson, those reviews come after the book’s publication, when it’s too late to change anything). You might get a half-dozen readers of family and friends, and all of them will have their own thoughts—sometimes their advice will directly contrast. Trying to appease everyone is impossible.

So, how do you pick who’s right? What’s the best way to sort through those comments?

Maximizing your feedback is a three-step process.

1. Open yourself up to feedback.

Understand that when you ask for constructive criticism, you ARE going to get it. It’s not just that your draft is imperfect—people read differently when you ask for their help. The request implies that the work is unfinished or flawed, and more importantly, it implies that they can improve it.

This flips the natural order of things: When reading a book for enjoyment, the audience typically assumes the author has all the answers. But when giving feedback, readers assume they have the answers—and they think it’s their responsibility to find them.

This often goes doubly true for other writers.

Work out who you want to criticize your draft and who you want to enjoy your completed book. Having your parents or partners tear your prose and plot to shreds can be a bad idea. Sometimes it stings more when your favorite people give you a negative review. At the same time, however, you want to empower your readers to tell the truth.

Beggars can’t always be choosers, but in my experience, the best feedback comes not from your best friends but from avid readers who are familiar with your genre. Try joining a book club and asking whether people have interest in reading your book—posting on social media for volunteers from your friends can be better than directly asking (trapping) individuals into the job.

Sanderson uses the same reading/writing group that he joined during a creative writing class at BYU. That’s a great way to find a consistent group of readers who understand your voice and goals.

2. Cultivate the feedback you need.

Another great aspect of Sanderson’s writing group is that they’ve been together for decades. They know what he wants from his readers.

Communicating your expectations about feedback is an absolutely essential step in getting something you can actually use … and ensuring that your readers don’t waste their time. For example, I don’t want my readers highlighting a typo in a first draft when I’m weighing whether to cut the entire chapter. Here are two ways Sanderson recommends asking for feedback, which I think are really smart.

Start by highlighting the best parts of the book.

There’s a Ben Affleck quote I love about this. While co-writing the film Good Will Hunting with Matt Damon, Affleck said, “Judge me by how good my good ideas, not how bad my bad ideas are.”

It’s important to fix the flaws in your book, of course, but it’s more important to understand what makes your story special. Is one character popping? Do you have a scene that blows people’s socks off? Do you write action really well, or dialogue?

You build the whole book around its strengths, not its weaknesses.

Ask “where” questions.

Sanderson calls the answer to these questions “reader response” feedback. “Where were you bored? Where were you confused?” This gives your readers—especially readers who may be offering feedback for the first time—a specific, easily actionable way to help you.

I recently experienced this exact comment in my own book. I introduced a new character in the middle of the book, and with that character came an influx of character-specific jargon. My beta reader said “I was confused and bored” by all of these unfamiliar terms, and it was such an easy fix to go back and make that section more accessible.

3. Don’t delegate decision-making.

Sanderson abides by a simple maxim: When readers tell you that something isn’t working, they’re almost always right. When they tell you how to fix it, they’re almost always wrong.

I wish more than anyone that the readers weren’t wrong. Every time I get stuck on a plot point or character decision, I wish someone could just come along and tell me what to do. Authors are making hundreds and thousands of decisions over the course of a book, and that comes with understandable fatigue.

Your beta readers are (usually) not going to be a cure-all. So, don't go chasing your tail to appease everyone. In fact, don’t just implement anybody’s feedback without evaluating it first. Use their feedback as a moment of reflection and examination, but never forget that you’re the one with the power here. It’s your name that goes on the cover, and you call the shots.

Sanderson breaks down big problems.

Writing a 1,000+ page book is scary. Doing multiple revisions of a book that big is also scary. But if you’re familiar with the format that Sanderson has developed in The Stormlight Archive, you’ll see how he cleverly breaks the monumental problem of writing a big book into smaller pieces. To start, each book in The Stormlight Archive contains five parts with a series of interludes in between each part. Each chapter starts with an epigraph.

Already we can see this 1,000-page book broken down seven ways. Now, that can be broken down even further by point-of-view characters. Each book tends to focus on one character’s backstory, which accounts for about 100 pages in total, and the rest is split between a series of other primary, secondary, and even tertiary characters.

The end result is that no one character holds the burden of the plot alone. In Rhythm of War, Book 4 of The Stormlight Archive, Kaladin has the largest number of chapters at 49. According to Coppermind, those chapters make up about 99,000 words (or 400 pages). That’s the length of an average book—not so daunting.

We’ve already spoken about how he breaks down each day into attainable writing goals, which is another way in which he sections off and systematizes his progress, but one other problem I’d like to highlight comes from Oathbringer.

Sanderson’s beta readers highlighted that his characters had a motivation problem—the plot demanded that they do one thing, which went directly against their goals. Many writers would try to redo the entire 500-page section of the book.

Sanderson simply added a quick scene at the start of it. In the finished draft, a character has a vision, telling him to go to the place Sanderson already intended. That way, the characters can continue toward their goals, but the reader is always drawn back to the promised destination.

It’s a simple fix, but it meant adding a five-page scene instead of changing 500.

Sometimes a big problem is fixed with a small solution.

Sanderson cheats.

And you should, too.

That is to say, you shouldn’t just expect to sit down at your desk and begin to churn out a 1,000-word epic. Give yourself a head start.

Sanderson is a notorious outliner who likes to meticulously plan his setting, magic, and plot. He allows his characters some freedom during the drafting phase to crack jokes and express their personalities, but most of the big choices are done before he ever starts typing.

One reason for this is that Sanderson has said many times how much he resents revising. In the early days of his writing, Sanderson only ever wrote first drafts, finishing one book and immediately starting on the next. In fact, he wrote 13 books before he got published!

While I believe it’s important to do multiple drafts, the more that you plan, the less drastic the changes need to be from your first draft to your final.

It’s like the old saying: measure twice, cut once.

Oh, and remember how I said that Sanderson only ever wrote first drafts when he started? How he had 13 unpublished novels? One of those books just happened to be The Way of Kings—an earlier attempt, which Sanderson wrote on his blog “is very different from the published book. Think of it as set in a different universe with a completely different plot.”

He mentions that The Way of Kings Prime was written in 2002, while the published version came out in 2010. Think about that: While we now think of The Stormlight Archive coming out every three years, it took eight years to go from one draft of The Way of Kings to the finished product! That’s eight years to further develop characters, ideas, and plot … to start exploring sequels.

Now, it’s typically inadvisable for unpublished authors to start crafting sequels before establishing an audience for the first book. However, even if a Book 1 is rejected or needs rewrites, it doesn’t mean that all of the effort you put into it was wasted.

Simply by writing a book, you give yourself the confidence that you can do it again. By accepting feedback and using a critical eye, you can improve your skill as a writer. Practice is preparation, no different from creating an outline.

If you keep at it for long enough, your failure will give you the tools you need to find success. With luck, your work will find its audience. Sanderson kept writing after 13 failed novels. Even The Way of Kings was originally rejected, and now it’s part of the biggest series in the world.

If that’s not worth celebrating, I don’t know what is.

You can teach yourself to write like Sanderson—I should know. I wrote this article in one day using the tips above, and it clocks in at just over 3,500 words.

Take that, Brandon, and congratulations on Wind and Truth. I can’t wait to read it.